Showcasing music, podcasts, performances, and other listenable material in China.

Last post May, 2016

Djang San (Zhang Si'an) 张思安

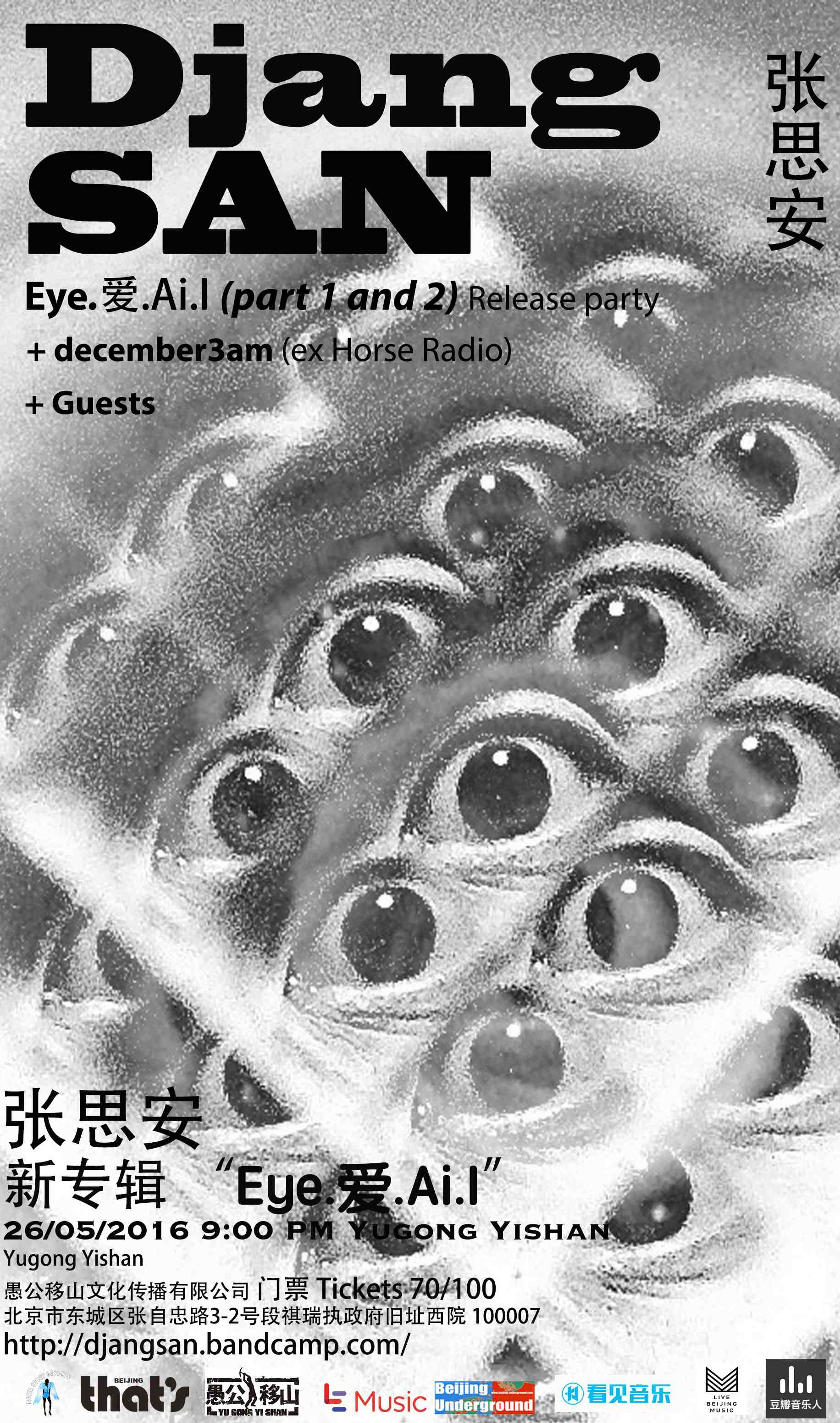

Djang San meets up with Loreli very early (like 1:00p.m.) on a Saturday in the extremely noisy Fang Jia hutong for an unusually philosophical chat about electrifying traditional Chinese instruments, the disconnect between what we see and reality, and "The Final Countdown" for crickets. Djang San will be playing a record release show at Yugong Yishan on Thursday, May 26th for his new double album Eye.爱.Ai.I (1) and Eye.爱.Ai.I (2) which can be found on his bandcamp page.

Posted May 24, 2016

About Djang San:

Jean-Sébastien Héry was one of the first foreigners to write songs in Chinese and to sing those songs to a Chinese audience in Beijing. Re-inventor of Chinese classical instrument zhongruan, philosopher, poet, composer, guitar hero, DJ, one man orchestra, music pioneer and explorer of new sounds, Djang San has been doing music in China since the year 2000. An artist with many faces, Djang San has also won the battle of the bands in Mainland China and Hong Kong against 100 bands in the year 2011. Djang San has so far released 35 albums, the music styles of the albums range from Jazz to electro, rock, classical music, experimental music and more. Creator of a theory of intelligence, the personality of Djang San takes many different shapes in his many different projects. As a one man band, Djang San plays seven different instruments on stage including guitar, flutes, electronic devices and synthesizers. Djang San + Band is an extension of Djang San, a trio based on an electric version of Chinese instrument zhongruan he has created himself in 2014. Djang San also composes and records music for films. He has been interviewed countless times and had documentaries done about him on Chinese TV. His new album, Eye.爱.Ai.I, was released on May 16th, 2016.

Transcript of interview:

Amy Daml: Do you want to introduce yourself to us?

Djang San: People know me as Djang San. I’ve been in Beijing forever, more or less. I’ve done 35 albums. Next week, I’m releasing the 36th album, which is called Eye.爱.Ai.I. It’s a play on word about the idea about the connection between what we see and what we understand. The music I think is a bit different than what I usually do. I’ve tried to do something that was more about feelings and less about technicality, which is what I usually do. For me, it’s one of my best, probably. It’s a double album. It’s 50 minutes of music, so it’s pretty long too. I’ve invited some people on the album. I’ve got Stéphane (Balagna) on trumpet. I’ve got Elenore, who is an Italian singer; she’s improvising on one of the tracks. I’ve got Nicolas Mège on drums. I’ve got Clancy (Lethbridge) on the bass, and also Chris O’Young on cello. I’ve done all kinds of stuff, like ranging from rock music to African Afro-beat, like this kind of feeling, and then it goes into a lot of different styles, but it’s more natural than the other albums before, I think.

AD: Why do you think it’s more natural when you have so many different styles?

DS: Because I asked myself less questions when I was composing the songs. Usually, I think a lot before I record something and sometimes I feel like I’ve lost a bit of the feelings in the song by overthinking the songs. I think by just focusing on the expression of the idea in the song or in the music, it makes it more direct and easier for people to listen to it as well.

AD: I noticed that you do have a lot of different styles. I listened to probably three quarters of the album and I thought every single song sounds completely different. It’s a completely different style, maybe not even the same artist.

DS: Yeah, I mean I have this problem. People sometimes tell me I should release less albums and focus on one thing or something, but I feel like if I do that I’m kind of missing the point because I just compose a lot of different things everyday. It’s a part of me so if I just get rid of a part of me, then it’s not really me on the album. It’s kind of strange. So I just decide to do as much as I can because that’s just the way I do it.

AD: I mean, 35 albums is a lot, right? You have a lot of albums. Do you ever think that maybe if I stopped and worked on one that I would have a better response?

DS: Yeah, because what people say is that I release too much. But it’s stupid actually. I think a lot of people say I release too much because they can’t release anything. People can record an album for a year and it’s not even that good. I mean, I have the ideas and I want to do it so I have no reason not to do it. And that’s very simple. On this one actually I took more time because if you think about it, the last one came out five months ago, so it’s actually quite a long time. Even though maybe the time is not that long but I put a lot of effort into every album that I do. If I took a year, it probably would not be different.

AD: Is music your fulltime gig?

DS: It is three quarters of my life, yeah.

AD: What’s the other quarter?

DS: It’s a secret.

AD: You totally make jingles for commercials, don’t you?

DS: I’ve done this type of thing, yeah. I’ve also done music for documentaries. I’ve done music for a documentary about surfing in China, and I’m doing one about cricket fighting. Someone asked me for music in California for film lately. So it’s a little bit of everything.

AD: What does music for cricket fighting sound like? I just imagine The Final Countdown.

DS: Yeah, something like that. No. Actually, I met that guy.

AD: Did you?

DS: Yeah, I met that guy, yeah. When we won the Battle of the Bands with The Imaging Insurance Salesmen in 2010 and 2011, we went to play in Malaysia, and one of the judges was the guy that wrote The Final Countdown.

AD: What? No. Did you know that before you played?

DS: I didn’t know but then we went there with Rustic because they won the year before. Rustic, the Chinese punk band. Ricky, the bass player of the band, was a complete fan of that guy. So I didn’t know the guy at all. I mean, I don’t really like the song. He came on stage and he played The Final Countdown with a band of Filipinos.

AD: No, he did not.

DS: Yes, he did. And he was the only original member. He played guitar like very, very well, but it was kind of strange cuz he was the only [original] guy and the other guys were all Filipino in Malaysia. It was kind of a weird scenery, a weird thing to see. And then I remember he was complaining at the hotel. We were in a five star hotel with a swimming pool and stuff that was really good, and then the guy was complaining because they were playing the same song every day, you know. But the guy had been playing the same song for 30 years and making money on the same song, and he was still complaining. That was kind of funny.

AD: And of all the songs to have to play for 30 years...

DS: It’s The Final Countdown. Yeah. It’s probably his main way of making money in the world.

AD: That’s kind of sad, huh?

DS: It is. Yeah.

AD: Do you every worry that could become your life?

DS: Well, I don’t really have a song that works as much as The Final Countdown, so I’m not really worried about that. I don’t think that’s going to become my life. I think my life is about composing music; it’s not really about the one-hit stuff. I don’t really think about doing a hit. I’m not focusing on this.

AD: Have you had any songs that have become kind of like hits?

DS: Yeah, I’ve got Xinfu Zai Nali?, you know, Where is Happiness? I’ve got like three or four versions of that song. It’s one of the songs that’s really liked by the Chinese audience and the foreign audience alike. Everybody likes this song. I don’t know why. But everybody likes this song and the different versions that it has. I’d say this is one of the songs that really got the audience. There’s another one, an instrumental one called Bridges that works pretty well with the people as well. Also, because I check what people listen to online, what songs people listen to the most, and I’ve found out over the years that there are 5 or 6 songs that people really like that always come back.

AD: Are those your favorite songs too?

DS: Yeah. I mean, not necessarily, but I like the music that I’ve done that is really strange, and I don’t really like the things that people would call ‘normal’ music or whatever. As I tend to think less about this stuff, I think the music is becoming more enjoyable for people now than it used to, because I think less about the artistic part of it and I think more about, like, just feeling it and feeling good about doing it as well. I mean, it can sound kind of strange but I’ve been through a lot of different things with music and I don’t know, maybe my life is becoming a bit easier these days. So I feel less the need to explain myself so much anymore. So that’s why in the new album I still use Chinese instruments, but I’ve tried to instead of just exploring the idea of being the foreign white guy who plays Chinese instruments, I’ve tried to just really use the instrument in a way that I don’t really think about anything; I just think about the music and how I play it. That’s all. Just, are the songs good or not?

AD: Everybody knows you as the guy with the weird guitar, right? Did you start to feel a bit like a monkey? Sometimes as foreigners here, we get that feeling of ‘oh, look at the laowai doing the Chinese thing.’

DS: Yeah. When I started to play Chinese instruments around 2000 and for a few years, the Chinese audience, some of them would be very angry with me because I was playing Chinese instrument and I didn’t have the right to play Chinese instruments. That was a part of them, and there was a part of the audience that was really interested in me doing that because they knew about these instruments. But mostly people just didn’t know about the instruments. They didn’t even know that the instruments were Chinese. They were asking me, like ‘is this a French instrument or a Chinese instrument or where is it from?’ They were not sure about it so they would come to me and ask questions. So my answer to the people who say because I’m a foreigner I can’t play Chinese instruments, is like ‘Chinese people shouldn’t play guitar.’ This is completely stupid. And to me, it’s kind of racist as well. I think we shouldn’t be stuck in the idea of coming from somewhere or anything. We do whatever we want because we are all human beings and we just have the ability to do anything we want. If a Chinese person or white or whoever can play guitar or any instrument, or even French traditional instruments, then I say go ahead. There’s no reason why people shouldn’t do that. So it’s the same for me. I don’t see why I shouldn’t do it. And I think actually doing it is helping people to understand that as well. There is no boundary to what we can do. The only boundary is really a mental boundary, and actually we can do whatever we want.

AD: Tell me a little bit more about the concept behind your new album, the disconnect between what we see and what we understand.

DS: We are often misguided by what we see. I mean, images and manipulated all the time nowadays. It’s very easy to create fake reports and to create fake information everywhere. And so we are always thinking that we know what we see but we actually we don’t. That’s one of the things. We are always limited by our own perception of things. You know like two years ago I did an album, called The Theory of Intelligence, which is a theory I created. So I created this theory of intelligence, which is based on the idea that we are limited by our senses and we can only understand the world through our senses. Because of that we can never really understand what’s around us. That was the basis of how I developed the theory afterwards. So this album, Eye.爱.Ai.I…is like eye, like for eye, the thing we have on our face; I like myself I, like a person; ‘ai’ like ‘love’ in Chinese; and ai like A.I. artificial intelligence, something like that. So the idea is really that you can manipulate what’s around you and we can all do whatever we want to try to do. So this is like going beyond the vision and just, as I told you, and speaking more from the heart with the music in that album and less thinking about the vision of what people can have of me being this guy who plays Chinese instruments. I know it’s hard to understand, and also because a lot of my image is based on that, but I’m trying to overcome this because I have to say I’m a bit tired as well to be that guy. So I have to move on. I always have to do new things because otherwise I also really get very bored. So I’m always trying to create new things and little by little I create new concepts and new ideas to try not to be too much according to an image.

AD: Is there anything else you want people to know about you, your music, or your new album?

DS: Well, what there is to know about me is that I’ve been doing music in China for the last 15 years. I’ve done 36 albums now. I’ve played about everywhere in China, almost all the festivals. Djang San and Band, which is the trio, so me, Clancy on the bass and Carlo on the drums (sometimes Nico on the drums as well) we played in Korea, in Seoul in October last year. And this summer we’re going to play in one music festival in Hokkaido, in Japan. It’s the first time for me to go to Japan. It’s cool because it’s apparently it’s a beautiful place. It’s the northern island of Japan. I’ve never been there but people tell me it’s great.

AD: Is that the Fuji Rock festival?

DS: No, no, no. Fuji is like way bigger than that. But it’s one of the biggest world music festivals in Tokyo. Sorry, in Japan, not Tokyo because it’s in Hokkaido. Fuji’s in Tokyo. Clancy’s going to Fuji to go see The Red Hot Chili Peppers. I’m not a big fan of that band, but, I mean I like the early stuff.

AD: Are you ok with him going to see them?

DS: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I’m ok. I’m ok with him going to see them. Playing in a world music festival in Japan actually means a lot to me. It means recognition in Japan, which I never expected would happen, so it’s a very good thing. I played Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Korea and other places before, but Japan is like, because I’ve never been there, it’s going to be very interesting, I think. And it’s going to be a way to expose something new because I’ll probably be the first musician who plays this instrument, an electrified version, to play in Japan. So I’m not Chinese, and I’ve played this instrument and I’ve electrified this ancient Chinese instrument and I’m probably going to be the first to play it in that form in Japan. So it’s very interesting.

AD: Also, not many people electrify that instrument that you play. What’s it called again?

DS: It’s called a zhongruan. I think what happened is that, people probably thought about it before but they never pushed it to the point where it becomes the center of the music. In the way that I’m doing it, I think it’s never been done like this before. I also do it with the pipa now, so I’ve electrified the pipa as well. Actually on the new albums there’s a little bit of electrified pipa as well. So it’s not only the zhongruan anymore, it’s also the pipa. I’m the first one to do that, like to really push this idea of using these two instruments into modern rock and jazz in this way. It hasn’t been done before. That’s why it’s hard to push this idea as well because people don’t understand, because it’s new both for Chinese and for Westerners. No one has done that so people are like ‘why do you do that?’ It can sound kind of stupid because I could just play guitar, which I also do. I play guitar very well, but I’m bored. Everybody plays guitar. What’s the point? Aren’t we supposed to try to create something new and try to exchange ideas with people and create a new idea of music and make things progress or are we just supposed to reproduce what people have been doing for the last 50 years again and again? I don’t understand. I think it’s boring. So yeah, I want to do something new. That’s why I started to do that 15 years ago, the first time I came. I wanted to see what I could do with Chinese instruments and I found a way because I think that is the way that people are going to understand each other more as well. If we just reproduce what’s been done again and again, for me there is no interest in music. I mean, I like pop music and I like rock music and everything. I like it as it is, but that’s not the way for me to explore it. The way for me to explore it is to really make it progress. I think art is always progress and music has to be as well. When you think about rock and roll in the ‘50s or in the ‘60s, I’m sure a lot of people were like ‘what is this thing? I don’t like this. I want to listen to...’

AD: Yeah, we all saw Footloose.

DS: Yeah. Exactly. Or like the people who hated Elvis because they thought this is the devil’s music or whatever. I mean, I’m not pretending to be any of these guys because I’m just a French white guy stuck in Beijing. I think the kind of ideas that I’m supporting and developing, I think that’s the origin of these kinds of things. You can’t have something new if you don’t try to take the risks to have people calling you the white guy who is playing the Chinese instruments or just a ‘fake Chinese guy’ or something, which is not what I am. I don’t pretend to be Chinese or anything. I am completely French. And it’s impossible. You can’t become Chinese because they won’t let you anyway. I think people maybe have a misguided vision of me when it comes to that, but in fact, my idea is more like going on creating the cultural bridge and also trying to open people’s minds, both in China and in the West, about the possibilities of communication in the modern world. A lot of people speak different languages now and we don’t have to be stuck in one idea of what things have to be. There’s lots of options and there’s lot of things to dig into, and we don’t have to just put up walls and stuff because that’s the end of the conversation. And we all know what happens when the conversation ends. Bad things.

AD: Can I ask a technical question? How do you electrify a traditional instrument?

DS: Well you take the instrument and you electrify it.

AD: But how do you do it?

DS: When I had the idea, I looked up how people did it with guitars. I looked up YouTube and I didn’t find any videos about electrifying traditional instruments, so I had to use the idea that people do for electrifying a folk guitar. I used the idea and I applied it to the Chinese instruments and then I had to modify that idea again to avoid a few more technical problems. I’m not going to go too much into it, but it was a two or three step idea to make it happen in a way that it would sound good. Because you can do it but it might sound bad if you don’t do it well. I wrote on the paper the different ideas and how I could do it and then I imagined the result. I always do it like that. I just write the steps on a piece of paper or on the computer. Little by little I find I have the concept completely in my mind, like I can see it. This is how it’s going to work and then step-by-step I start to do it, and then what I wanted is there. It’s always like that, I know in my mind it’s going to be like that. And I see how it’s going to go wrong if I don’t do the right thing and how it’s going to go well if I do the right thing. It’s like I’m on a road and I can see different tracks I can take, and I can see which one is the good one and lead me to the right result.

AD: Did you ruin any instruments in the process?

DS: No, because I didn’t have much money at the time to make this kind of mistake and I didn’t want to destroy an instrument. That’s why I thought very seriously about it before doing it. I really thought very carefully about what I was going to do and that’s why it worked because I had to be careful. It worked the first time, and then the pipa sounds even better.

AD: Thank you very much. Good luck on the show. Tell us the details again.

DS: The show is on the 26th of May at Yugong Yishan in Beijing, the famous venue that opened maybe ten years ago actually. The show’s about having a party for releasing this new album, called Eye.爱.Ai.I. There’s going to be a few guests on stage. There’s going to be videos and it’s be very interesting because it’s going also two parts, one part with Carlo on the drums and one part with Nico on the drums. So two different parts for two different shows, but in the same night. We’re going to have december3am opening the show. They’re based on two members of the band that was called Horse Radio before. I think it’s going to be a great show. I’m really happy I’m doing this. I’m also doing this because the fact that we got invited to Japan really motivated me to push the things a bit further. I’m also helping to organize the Fête de la musique this year, the French day. We’re going to have a few gigs as well on the 19th and 21st of June.

AD: Great. Well, thank you so much.

DS: No problem.

Loreli had lots of help on this piece from:

Angela Li 李梦格 studied in the U.S. before returning to her native Beijing in the summer of 2014. In March 2016 Angela became the official translator for Loreli China. Enjoy her work.

Michael Cupoli is an electronic musician and audio mastering genius. You can see him perform as Noise Arcade or with his band Comp Collider.

Brad M. Seippel stepped in last minute to help us out with transcribing and translating audio from the interview. He is also a musician who uses Meng Qi instruments in making music.

Meng Qi 孟奇

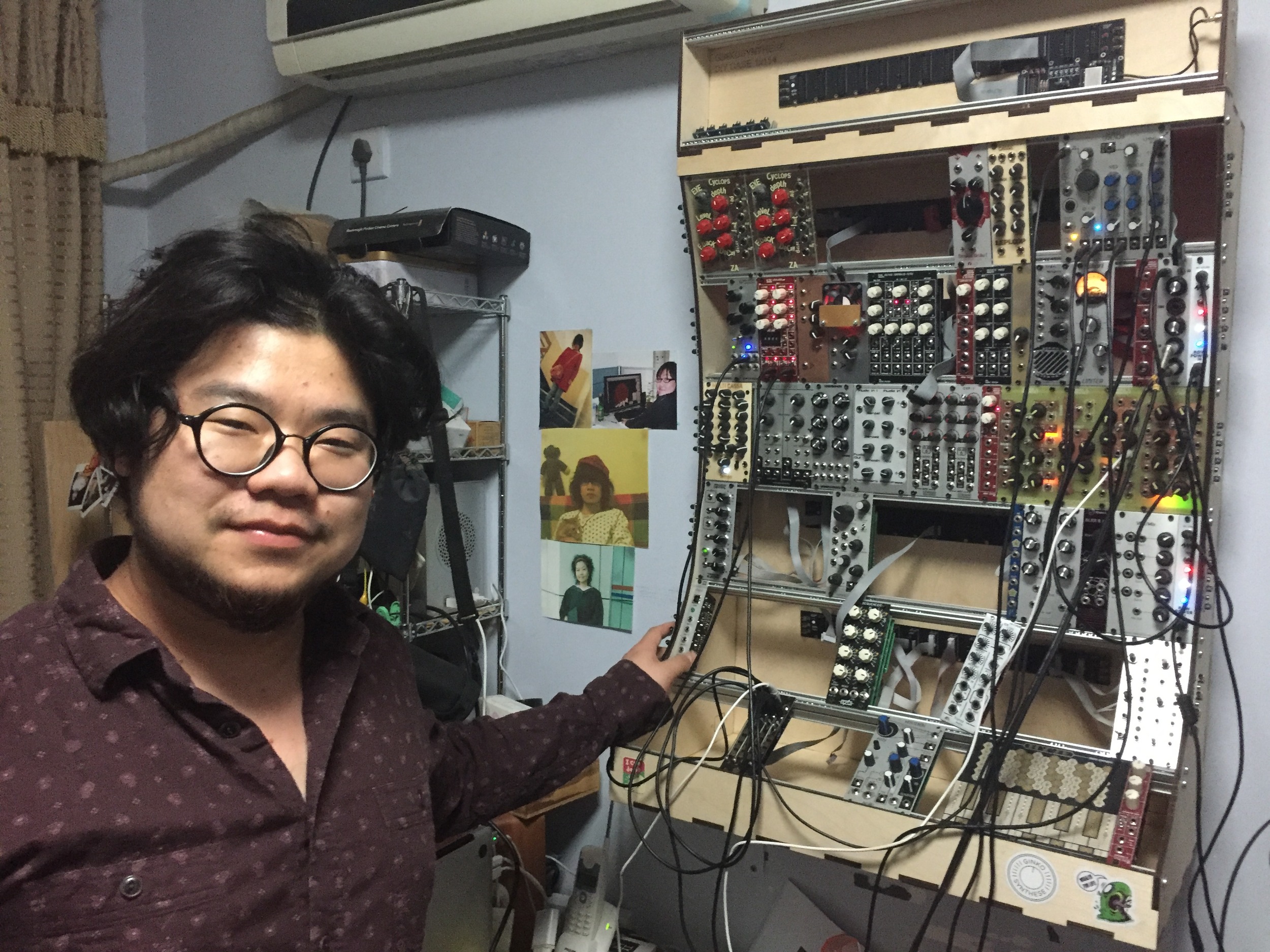

Meng Qi invites Loreli over for a chat, some delicious hotpot, and a tour of the ultimate electronic musician's laboratory of cables, patch bays, soldering irons and cats! If you wanna catch this guy in action, using his own self-made synths and other equipment, make sure you get a front row place at Old What? Bar this Saturday for a collaborative showcase put on by Live Beijing Music and Seippelabel. Mastering for the music on this piece was done by Michael Cupoli. Check out Meng Qi's music and self-designed synths at mengqimusic.com.

Posted May 19, 2016

About Meng Qi 孟奇 (from mengqimusic.com):

Meng Qi is a musician with multiple identities. He’s not only a electronic music artist, but also a synth designer, a programmer and a teacher. Meng Qi had various music works released including “landscape in love” / “landscape on live” and more, and has published a series of modular synthesis tutorials on midifan mag and ZiHua.

He also had given instrument building workshops and lectures in de Cidade de Macau, Beijing Maker Space, Shanghai XinCheJian, Maker Carnivals, Shanghai Conservatory of Music, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing Contemporary Music Institute, Beijing Zajia lab and so on.

Meng Qi is a pioneer of Chinese contemporary digital art, and is fame for his music and distinctive devices and instruments, which have been using by electronic music artists all over the world.

孟奇是有着多重身份的音乐人,不仅是电子乐艺术家,还是合成器设计师和大学老师。孟奇发表过很多音乐作品,包括专辑《山水恋》《山水颤》等。他发表过一系列的模块化合成器教学文章(midifan月刊)和模块合成器教学视频。他曾在澳门艺穗节、北京创客空间、上海新车间、创客嘉年华、上海音乐学院、天津美术学院、中央美术学院、北京现代音乐学院、北京杂家实验室等地开设乐器制作工作坊及讲座。

孟奇是当代中国数字艺术的先锋人物,他创造的音乐和独一无二的乐器和设备让他名声在外。这些设备已经被世界各地的电子音乐家所使用。

Interview Transcript

Transcript translation: Brad M. Seippel, Live interpreting: Angela Li 李梦格

Loreli: Please introduce yourself.

Meng Qi: Hello everyone my name is Mengqi. I’m a synth designer, teacher and musician.

L: How did you get into making these synths?

M: I started making synths in 2007. I wasn’t that satisfied with the products on the market at the time and wanted to make instruments that could express what I had in mind.

L: How did you start making them?

M: At first I would follow other people’s circuit diagrams. A lot of people doing DIY electronics share information online and I started working on simple schematics that way.

After that I began increase my knowledge of digital and analogue synthesis. This included basic analogue circuitry and digital design. Later I slowly developed the ideas that I had in my mind.

L: Are your current models all your designs or do you still use other people’s diagrams?

M: I use all my own designs now.

L: They are really cool. They look like toys.

M: They are toys.

L: Would you describe your music as “Toy Music”?

M: Yeah, sure. You could put it that way.

L: Since you’re also a teacher, what’s the basic principle of a synth?

M: Well, basically it’s a human thing to create a sound or oscillation and control it. From there we need to control the pitch and timbre in order to play melodies and make harmonies as well as adjust the volume to express the appearance of the sound. There are different means in creating a sound. In my mind there are three properties to sound and over the years there’s been a great deal of exploration in it. There are many scientific methods in creating and controling sound, for instance subtractive and additive synthesis, frequency modulation and amplitude modulation. These are many techniques typically used in the synth world. If your are interested there is a lot of information on South Synthesis online.

L: You also have lots of information online and often do workshops, right?

M: Yes, I have videos online. Actually, last year I worked on a series of tutorials with an educational company called Zihua Creative. These videos provide information on Sound Synthesis for a fee. Besides those most of my other videos are about the products that I make.

L: Do you make anything besides synths?

M: Well, I used to cook a lot more before, but not so much anymore.

L: Is there anyone famous or important people who use your synths?

M: There’s one artist who I’ve listened to since I was young that I’m quite proud to say uses my devices and that’s Trent Reznor ofNine Inch Nails.

L: Oh yeah, there’s a picture of him on your website.

M: Yeah, that’s in their studio. I made those instruments on the table.

L: Did you get to meet them?

M: No, not yet. I’d like to go to America and meet them though.

L: That’s pretty cool they’re using your stuff. How does that make you feel? Does it make you want to raise the price?

M: It makes me feel really happy. Oh, not at all.

L: Do any local musicians use your stuff?

M: There are a lot of people in China who do. I’m not sure if you would know them, but Jason Hou and Li Yan just to name a few. Not necessarily big stars, but people behind the scenes if you will. Thruoutin uses a lot of his stuff.

L: Do you use your own equipment when you perform live?

M: Yeah, I don’t use anyone else’s stuff.

L: What got you into making music?

M: I guess it all started when I was really little. I was especially interested in music from an early age. I had a sense for it and it became my hobby. It’s hard to say. Why does anyone like music? I can’t really tell you, but from the beginning until right now I have never gotten sick of it.

L: Why electronic music?

M: When you’re little you don’t always have a choice of what music you learn. I didn’t choose electronic music, electronic music chose me. It’s a very solitary process and I like to put a personal touch to my work. I’ve been in bands before and it was a great experience, but with electronic music I can put whatever i’m thinking directly into my work. There’s simply more freedom with tones and harmonies that traditional music just cannot obtain. It’s not to say that I’m super qualified or anything, it’s just a natural development. Sometimes when you are playing with an idea you’ll find a really deep beauty in it and that makes it even more interesting.

L: Do you work with other people?

M: I have a group (Liquid Palace). I collaborate with people and it’s not that I only do one or the other. It’s that the style or workflow of producing stuff on my own is more suitable in my case. There’s a lengthy working method to it, but a high level of freedom within it. If you take traditional music into consideration for example, there are more people involved and not to mention all the writing that’s involved. In more traditional collaboration it takes time to get going and execute the vision that the composer might have. I feel that the possibilities are greater and the preparation time is less. Some people might disagree, but I consider it to be a quicker, freer and more extreme way of doing things. Anyway, that’s just how I see it.

L: What’s the scene like in China?

M: It is getting better everyday.

L: Is it mostly Chinese or is there much collaboration between international and local artists?

M: There a bit of everything.

L: How would the scene here compare to other places?

M: Well, honestly I’ve only really been to Europe and it’s not that much different. You could say it’s a little more vibrant here as there are more people.

L: You have several albums up on your website which i’ve listened to. Do you have anything else coming up?

M: Aside from making these interments I want to spend more time producing my music. My plan is to invest more time using my instruments in my work.

L: When’s your next show?

M: My next show is on April 28th at fRUITYSHOP. (Meng Qi is also playing on May 21st at Old What? Bar)

L: What’s the name of your website?

M: www.mengqimusic.com

L (2nd interviewer): When electronic music was in it’s earlier stages there were bands like Kraftwerk who would often encounter difficulties with their equipment when playing live. One night it would be amazing, but the other night might have a lot of problems. Have you ever experienced anything like that before?

M: When you play live it’s never going to go exactly just the way you want it. Making interments is the same way. There are two types of failures. Sometimes it’s the gear that malfunctions and others it’s when the result doesn’t match up with the initial intention of the artist. As long as it’s successful then I’m happy.

L (2nd interviewer): Many of your instruments look like hybrids of acoustic instruments and electronic ones. How do they work together?

M: That’s a good question. In fact, over the years a lot of electronic instruments have been incorporating aspects from more traditional instruments in their design. Traditional instruments are quite sensitive and electronic instruments can’t fully replicate them. Take this drum for example. If I hit it with a stick, bottle or even rub it with my hand the sound is completely different. It’s the same with a violin. You can bow it or pluck it and you’re going to produce a distinctly different sound. On the other hand with something like a keyboard you’re only going to get the intensity of the sound.

So with electronic music there are two significant ways of thinking. The first idea is how we as humans touch acoustic instruments to make sounds. For example Haken Audio’s Continuum (http://www.hakenaudio.com/Continuum/) or Madrona Labs’ Soundplane (http://madronalabs.com/soundplane). These instruments do a good job of encapsulating how people actually play.

The second type of thinking is through Audio-Engineering. An example of this might be by patching different instrument cables together in order to make new sounds, which do not exists in the natural instrument world. You’re not actual playing notes or timbers, but rather playing the connections.

I’m actually working on a new product that will utilize this. Electronic instruments revolve around these two concepts. On one of my instruments I can produce a violin sound and through analogue synthesis I can alter it’s original sound. With an organic instrument you wouldn’t be able to do this.

Physics and nature are the best sources of inspiration when I’m designing instruments.

L: What’s your next instrument?

M: It’s a synth module that in which you use your hands to make the connections. With this interface you’re actually playing and connection signals between oscillators and sending them to filters. It can control anything really… pitch, timbre or volume and you can combine them all together to achieve a complex result. You might be able to see me use it in an upcoming performance.

L: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

M: Thank you for your time.

Interview by Liz Tung. Liz is a lady person who has been writing about music in China for about six years.

Dr Liu and the Human Centipede

Posted May 11, 2016

Despite having been around for six years and establishing themselves as one of China’s foremost hardcore bands, Dr. Liu and the Human Centipede have largely flown under the radar. That’s not a complete accident – though the band take their music seriously, as frontman Liu Fei explains, prominence in the China underground scene has never been one of their priorities. We talked with Liu the day after their album release show for Weekend Punk, their third full-length album, in the back office of School Bar, a local rock club of which Liu is part owner.

Dr. Liu and the Human Centipede are a Beijing hardcore band started in 2010. Their members include frontman Liu Fei, guitarist Wangzi, bassist Chacha, Cai Xiang on drums and Cao Pu on synth. They recently released their third full-length, a double album with fellow hardcore act Zankou, entitled Weekend Punk under the label Robust Husband.

Interview translation transcript:

Liz: So can you talk a little bit about how you chose your name? Is it based on the movie?

Liu Fei: Right, I really like the movie The Human Centipede. It’s a fucking cute movie. I just like the first one. And I feel like the movie teaches us how to see the world and how to see society. So I love the movie, so I chose it as the name for my band.

Liz: What do you think the movie has to do with society and seeing the world?

Liu Fei: You know the end of the movie made me think about what kind of person you want to be – maybe the first or the third or the second or the third. You want to see the shit and you want to eat the shit and shit the shit or you want to only eat the shit. I feel like that’s the three kinds of people in society, and which one do you want to become? Now in terms of whether you’re talking about Chinese people or all people generally, I think most people choose the second kind; it’s the safest position. I can see really fucked up shit, and I can also pass on fucked up shit to other people. But I don’t want to be that. I want to be the first kind of person – well, not that I want to be that kind of person, but I’d rather take that position than any of the others. I think… rather than… passing shit onto other people is not as good as just laughing about it.

Liz: So a lot of people who listen to this record or read or hear this interview don’t speak Chinese. So can you talk a bit about what the songs on this album are about and what inspired them?

Liu Fei: Ok, actually my lyrics are very simple. My lyrics have a lot of political elements, but I won’t like a lot of other Chinese punk bands whose lyrics are very direct because I want to use my own language to say out my own thoughts and ideas. But actually it isn’t just this aspect, it’s also life, but we very rarely sing about love. We don’t want to sing love [songs] (laughs). Yeah. But most of our lyrics have to do with my opinion/point of view about a specific thing. You know when I see the news on TV I think about I want to see something of the I don’t want to be a nerd, you know. I don’t want to be a stupid pussy. So I must think. AndI must sing the song. And make more people understand what I’m talking about. For example, [the song] “Die Like a Dog” (不得好死) is kind of about, so before there was a high-speed rail that collapsed, it was a big accident, and CCTV tried to conceal it. For example “Back to the Murder Field” is a new song about the military parade on September 3, 2015. I wanted to express this, but I didn’t want to make it too sensitive or obvious, that would make people as soon as they hear it go, “Oh, I know what he’s talking about.” And of course there are some things in our lives that if we don’t like them, then we’ll talk about it.

Liz: When you say the nerds or the pussies or whatever, what do you mean by that?

Liu Fei: I think it’s just some shabi who don’t actually think about things, the kind of people who just care about earning money and living a comfortable life. For instance, the kind of people who we call in China jianpanxia or wangluoxia (“keyboard warrior” or “online warrior” – people who express outrage about social wrongs online, but not in real life) – people who only know how to curse other people from the safety of their computers, these numb jingoists, these left-wing advocates. And they think of themselves as really active or like justice warriors, but they’ve just been brainwashed until they’re crazy. I think that’s what nerds are – people who just swallow these ideas from the time they’re young. And you don’t know how to choose what you want or what you don’t want. I think they are really shabi.

Liz: Could you choose one song from the album and just talk a little bit about what it means and why you wrote it?

Liu Fei: Like “Dingfuzhuang Thugs” (定福庄暴徒) is probably our most famous song. It was also used in a Jackie Chan movie, a kung fu movie, as the theme song (Police Story, 2013). But they didn’t know what it was about. The truth is, it’s about a very anti-Japanese period in China in which, because of the Diaoyu Islands, there emerged this problem in a lot of places with thugs who would go around smashing cars or use this opportunity to hurt people. Now actually these people have no idea of the Chinese government's real motivation. Because the government knew that there was a lot of unrest, and they needed somewhere to transfer this anger against the government, so they realized they could move that over to the Diaoyu Islands Issue. And let's be honest, who do the islands truly belong to? Not you , in any case. Regardless of who they belong to, you need a visa before you can go there. So this song is about that; it's telling people to stay awake. Because at that time, I did see a lot of so-called patriots going around smashing Japanese-made cars, attacking Yoshinoyas and then being taken away by the police for disturbing the social order. Fuck, these government agencies will be exposed. So the meaning of these lyrics is nobody remembers that you occupied the streets - you are all just puppets, government stooges. Under normal circumstances I won't explain the meaning of the song, and anyway every person who listens to the song will have a different idea of what I mean.

Liz: Do you not worry that writing about things like this, your band could get in trouble if someone from the Culture Bureau hears it? Or do you think that the lyrics are vague enough or that they don’t pay enough attention to rock music that they won’t care?

Liu Fei: I just don’t care. Because Human Centipede has been an “amateur” band from the beginning. So if you say I can’t play shows, fine, I won’t play. You don’t let me make music, then I just won’t make it.

Also my lyrics, even though people might be able to remember them very clearly, there’s not a single line of me like saying “fuck your mother” or whatever. I think we’re actually quite cultured. So my lyrics are more about venting or saying what I want to say. Also, I have no interest in participating in some fucking festival, some dickwad something-something “berry” festival in this place and this place. They can go fuck themselves. This is rock and roll, I just want to play what I want to play, so I just don’t care. But yeah, we don’t include the lyrics in our CDs – if you get it, you get it, if you don’t, you don’t. I don’t care. If we’re talking and you want to ask me what this song means, I’ll tell you. But you know I don’t want the lyrics to be a signal or be a bible or something else, you know. Like having people go, “Oh! I know that line, that’s from your lyrics!” I don’t like that.

Liz: I noticed that on this record you have a few songs that have not very traditional hardcore elements, like in COPS you have the girl who was singing, and then in another song you have the guy who is rapping. So why did you want to include these kinds of different elements in this album?

Liu Fei: First, we all love hardcore, but there are some differences. Like I like Black Flag and the Germs and Circle Jerks or like Bad Brains, 7 Seconds, like more traditional hardcore punk. And maybe our guitarist, who’s also Zankou’s guitarist, he loves Japanese hardcore punk like BBQ Chickens, Razor H. But we all love maybe Maxiumum the Hormone, a Japanese hardcore and metal-fusion band. But I hope because this is something we do for fun, so I hope that – like for instance, our bass player, he loves Ricky, he loves ska, so all of the members, when we practice together, we each bring our [influences]. So you have one, you have one, you have one, ok we get together. So it’s maybe not traditional hardcore punk. I want several elements to get together and [like, for instance] Beastie Boys I love. So I hope our music can include some old-school rapping and maybe even some ska, just as long as it’s fun. I think it being funny is important.

Liz: Hardcore is often thought of as an angry aggressive genre. Is that what it is to you? Like, when you’re writing songs, does it come from a place of anger or excitement, or what are your feelings when you’re writing songs?

Liu Fei: I think when I’m writing songs, it’s very simple, it just has to do with what I’m thinking about at any given time. So for instance if there’s something that’s been going on lately that I want to talk about, when I write songs that’s going to come out. So it’s not like they come from a place of always being angry or always being happy.

There’s often a specific thing that will make me want to write a song. And then because of a story or some detail, I’ll write a song, so actually for me… because I really don’t understand music, I just know how to write lyrics. So usually when we’re at band practice, they’ll come up with the musical concept and I’ll have a listen and then spplhy the lyrics. Anyway, for me it’s very simple. For example today, ok in the afternoon, I saw the movie of the fucking CCTV on BBC or CNN so I want to talk about something of this news, talk what I want to talk. So that’s how it works for me.

Liz: I think the hardcore scene in China is fairly small. I could probably count on one hand the number of hardcore bands in Beijing. Why do you think that is?

Liu Fei: I think hardcore is still a very small community in China; it will never become a mainstream genre in the world or in this society. But hardcore isn’t necessarily mainstream in the US either. So I feel like in China… how to say it? The people who know about punk are already pretty exceptional, so I don’t have very high hopes that people will be able to accept hardcore punk or something as extreme as trashcore and on and on. As long as everyone is doing their own thing, that’s good enough. And it’s also not a big thing for me that everyone accept it. If it became like this, I think… the country will be changed.

Liz: So in addition to this band, you’re also one of the owners of School Bar, which gives you a pretty good perspective on the punk scene and of course you’ve played in punk bands in the past, you’ve been involved in the punk scene for a long time. What would you say is its status at the moment? How has it changed in the past five to ten years?

Liu Fei: I think the most China punk golden age was maybe 1997 to 2005. So I think now punk’s time has kind of passed in Beijing, I think at least at School you can still see, not only punk, or not what I think of as punk, but a lot of bands that have the punk spirit. I think in the past, most people’s understanding of punk had to do with the music itself, or like how you dress, what your life was like, but I think now it’s more about spirit. A lot of people say School is a punk bar, but I don’t agree, you know. I think School is a rock and roll bar but our understanding of rock probably is based on the punk spirit, and for me, that’s enough. But I do think that right now Beijing and also Chinese punk is beginning to see a resurgence. At least that’s my hope.

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.