Showcasing upcoming artists in China.

Last post June 29, 2016

Angela Li 李梦格 studied in the U.S. before returning to her native Beijing in the summer of 2014. In June 2016 Angela became co-curator of Loreli China LOOK. Enjoy her work.

Ari Gunnarsson – A Film Kid and his Beekeepers

Documentarian, photographer

Interview 9th June at Amilal, Gulou

KL: So, you’re primarily a photographer?

AG: I came, actually, from a film background. I’ve been working more as a photographer in China because there are a whole lot less start up costs in any given project.

KL: I notice you’ve done portraiture for bands.

AG: Yeah, I just kinda started with The Harridans, I think a year or two ago now. Dan was seeing a photographer and she was unable to do a shoot so they asked me at the last minute. I think over an awful lot of baijiu at, if you remember, La Bas, they asked if I was available to shoot it and everyone involved was pleased with the result so I just kept doing photos with them and it opened the door to some other bands.

KL: Is that something that you enjoy doing? Is band photography a focus?

AG: Oh yeah, definitely. I’m happy shooting anything and bands are a lot more fun than kettles.

KL: Do you do a lot of commercial work?

AG: No, you know, I’ve done a little bit of food photography in the past and I’m available for it but, in my own mind, human beings are a whole lot more interesting than inanimate objects or even cute animals.

KL: Does video work come up very often? Obviously I’ve seen the Moon Tiger video, have you done many others?

AG: In Beijing it hasn’t come up as much. Video has been something that I have been pursuing my own projects on and I’ve spent a good chunk of my time over the past few years in Beijing but also leaving the country for at least four months every year and working abroad, where I’m still working in film, mainly documentaries.

KL: What role do you take on those projects?

AG: It depends, I used to work in the camera department then I was also ADing for awhile, which was never exactly my cup of tea, and these days on documentaries I’ll be camera operator, I will work as a second unit director and just take on roles like that for the most part. If the production is big enough or interesting enough I’ll work as a first AC, which is a focus puller.

KL: How do you find that work? How does it come about?

AG: Mainly good luck. No, I grew up in a film family. My mum was an art director, now she’s more of a producer and my dad’s a director and producer, Sturla Gunnarsson. Yeah, I kind of started out working on sets as a kid and, from there, moved into crewing when I was 16 or 17. Actually no, I might have been 15. I worked construction building a beer hall in Iceland. Yeah, I still would have been 15 then.

KL: If this comes from your family, did you ever want to do anything else? Is this like some families are like, you’ll be a lawyer, son, just like me?

AG: No, I think my parents did everything possible to push me towards a more stable career path. Based on growing up in a film family, when I was younger, I had an impulse to do anything else and avoid it at all costs… until I did and realised I didn’t like any of that stuff. So after stints in sales and labour, and I did a bit of teaching abroad, and realised I wasn’t too interested in any of those jobs. Particularly any job that isn’t project based. Working on something that has no end, for me, just sounds so horrible.

KL: I never thought about it like that but it’s so true. When something has an end goal it’s so much more satisfying.

AG: When you see what you’ve accomplished in a day in relation to something that will one day be completed and that you believe in, you can move mountains. You can do anything. The idea of sitting and fulfilling the same role in an endless process for the rest of my life, or until I save enough to stop doing it, is just grim.

KL: Did you move to China with the intent to actually concentrate on film and photography?

AG: I actually, first wound up in Asia through Japan. I’d been working on a documentary film in my last year in university which was called Force of Nature. I worked with my dad on that one, in the camera department. This was a film about David Suzuki, a last lecture he was giving trying to sum up his life, just about his life in general and his philosophy about things and that film took us, for about ten days, to Japan, to Tokyo and Hiroshima where his grandparents had been from and, after World War II in Canada, they eventually resettled in because, I don’t know if you know much Canadian history but, the Japanese were interned during the war and, following the war, they were told to resettle either east of the Rockies or return to Japan but they were not welcome back on the west coast of the country. So I ended up in Japan and, I’ve been all over the world, but I’ve never been to a place that was so completely alien to everything I knew. It fascinated me so I ended up going back there and teaching English for a few months and then for another year after that moving to Tokyo and modelling for a bit. From there, I didn’t want to do that for the rest of my life so I went to Korea. I didn’t like that too much so I hopped on a boat and ended up in China. I think the original plan was to travel down the coast of the country and then through Indochina eventually to Indonesia and just go as far as my money could take me and then go back to Canada and start real life. But I got to Beijing [brief interlude while Ari wrestles his sunglasses from an exuberant kitten, he may have called the kitten an asshole but the kitten deserved it] So I got on the boat from Incheon and five hours later I was in Tianjin. I didn’t speak a word of Chinese or have any idea what I was doing. I hopped in a taxi with some people who were heading to Beijing and, yeah, just kinda fell in love with the place and decided to stick around. I travelled around China a bit but realised it was kind of a special moment. This was back in 2012 and I’ve been spending a good chunk of my life here ever since.

NO VPN? TRY HERE: http://tv.sohu.com/20150720/n417126218.shtml

KL: Do you think that you can define that quality that Beijing has that makes it so appealing?

AG: I don’t know if I could define it right now but I can give you an example of it. A friend, Li Nian, he’s an actor here in China, if you saw Gone With the Bullets, he was the big general, the father of the girl and spoiled son with the big beard. So, I knew him from Canada, he worked as an actor in Canada for about eight years and then moved back to China and married a Belgian woman and they have two children. When I came to Beijing the first time, I got in touch with them and they let me stay in their siheyuan. It’s no longer there it’s been bulldozed to make a neo-classical hotel but it was a beautiful Ming dynasty siheyuan with a temple attached which was their art gallery. I got to stay in the east room and their children had the west room and they had the north room and it was about as spoiled an existence as I could get here in Beijing. He, today, as well as being an actor, playwright and director is also a furniture designer. He took me out to his furniture factory outside of the sixth ring road, way, way outside, it might have been Hebei, I don’t know. He took me out a few times to show me his operation, he had a big Tibetan dog out there he’d received as a gift from a monk that he was very proud of. We would drive out there and at one point it was farm fields and about two weeks later we came back and there was no farm fields anymore, it had all been dug up, the foundation was complete and the first storey of some major housing estate. A few weeks later I came back and the housing development was finished and the units were sold and he mentioned to me that this was all zoned agriculturally, whoever had done this had to have paid someone off to build the units and then no one would dare evict all these people en masse. I think, that level of energy and speed of development, not just in development but in everything, that appealed to me. Everyone here is a shark, they have to keep moving or they die.

KL: How does that work with your collaborative process? Do you find that you’re constantly meeting people who want to work with or that you want to work with?

AG: I’m constantly meeting people that I’d want to work with, in the film world. I have a very particular aesthetic and I, unfortunately, haven’t yet met too many people that are long-term collaborative partners here. I’ve worked with many people who are talented, and who I respect, but are not the basis of a long-term relationship.

KL: Not your soulmate?

AG: No, not yet.

KL: You said a lot of what you do here is your own work, what is an Ari Gunnarsson passion project?

AG: The one I’m working on right now is a film about migratory beekeepers. When I first arrived here in Beijing, back in Canada, I knew a documentary maker, Yung Chang, he made Up the Yangtze, and he suggested that I get in touch with his brother who was studying Chinese medicine. I was very late to a dinner in Dongsishisitiao which I thought was a different number at the time and he was a lovely person but I ended up stuck at the wrong end of the table with some very dull people. They worked in the cosmetics business and they were trying to move into organic cosmetics and they were very bitterly discussing the difficulty of getting Chinese organic honey because the beekeepers are migratory so there is no way to verify whether the flowers are organic or not. And I was struck with, there are migratory beekeepers, what the hell does that mean? They told me a bit, they didn’t know too much. I was just fascinated with this idea of a guy in a truck, travelling around China with a lot of bees so I did a little research, it’s actually a very difficult thing to research, there’s not much literature on it in English or Chinese, but eventually I found a beekeeping journal that sort of charted the course of one of these guys. I couldn’t get in touch with the guy but I got on the road and figured out where he was likely to be and thought there’d be other beekeepers there and got on a train and it was at Qinghai Lake where I found them. They were all set up around the lake and I walked along from beekeeper to beekeeper until found a guy that I found interesting. I didn’t know what the story was when I got into it, I just figured, a guy driving around China going from, the original course was Ningbo to Gansu via Qinghai but, the guy I ended up speaking to was from Hanzhong, Sha’anxi, and he goes from there to Yunnan, to Sichuan, back to to Sha’anxi, into Qinghai then up to Gansu so it’s pretty much the entire west of the country.

NO VPN? TRY HERE: http://www.tudou.com/programs/view/Z8KjQoIqFzw

KL: This is all done by car?

AG: This guy has over 200 crates of bees so several million bees and he and his wife basically set up and when they are looking to head out of town they look for a truck that’s going in the same direction they’re going, they pay the guy a fee to haul them to their next location and drop them off on the side of the road and they set up camp again.

KL: So, they’re living a purely nomadic lifestyle following their bees?

AG: They’re basically following the youcaihua and pingguohua, rape and apple flowers. The bees can basically feed off any flower and in the west bees are kept in a single location, the sort of honey that’s produced changes throughout the year as apples come in, or pears come in, whatever is growing they’re pollinating it and of course every plant’s pollen and nectar have different flavours and so does the honey. What these guys have found is that the honey produced by the youcaihua and the pingguohua is more profitable and better tasting so they follow these ones. When they get to Gansu there are certain high-altitude wild flowers that only grow there. They say that honey is the best they get but it’s a very narrow window.

KL: This is incredible. What kind of lifestyle do they lead? Do they earn much money?

AG: You know, the guy I’m talking to, I think he’s done quite well. He’s a well-connected man. He was actually a school teacher before he got into this. He grew up during a politically sensitive period and was unable to finish his education and he always felt like somewhat of a fraud teaching children when he had not been properly educated himself. He only received the post because his father had been a teacher and, I don’t know the exact details about this, in China there were the proper full teachers at the schools and there are different teachers who are less than that and the government made a deal with his father that after X number of years at the lower category, he would be made the full teacher. The father died a year before that happened and the officials in the town felt that the way to make good on the promise to the family was to give that job to his son who is the man that I’m following. Teaching didn’t agree with him. I think, for a number of reasons he doesn’t talk about as well as the ones he does and he said that he was giving his notice, they offered to train him and educate him and he said he’d already made up his mind. He wanted to be free, that life in small village as a farmer and a teacher, there’s no freedom there’s just obligations. On the road, he’s his own boss. It’s a hard life but he’s able to live the way he wants.

KL: Is it idyllic? Is it more hard work or more spending all day in fields of wildflowers?

AG: It seems like both. They work all day, especially him. He’s sort of a godfather of beekeepers up there. People come to him asking for advice - he’s been doing this for 26 years. He and his wife are working pretty well round the clock but once the sun goes down, there’s nothing to be done. With 200 hundred crates of bees, making royal jelly as well as honey plus pollen, they’re saving this pollen, some for sale some for feeding the bees in lean times. So, they’re busy but it’s not backbreaking labour. With the royal jelly it’s produced in little capsule they have for the bees about half the size of last part of my pinky finger and just scooping out these little things and filling little buckets with this very valuable jelly. And just going through and taking the racks out of the crates and putting them in a centrifuge and spinning the honey out, putting them back in and just sort of keeping track of the hive, making sure the bees are healthy. So, it’s hard work but there in some of the most beautiful places in China in the most beautiful times of year. You know, he seems like a very happy man. For his children he doesn’t want the same life, he wants them to have the exact life he turned his back on but he has no regrets about the decision himself. I think the greatest difficulty is that they live in an aluminium and canvas tent they set up with a satellite on the roof to watch television and army cot bunk beds and they travel with a couple dozen chickens, a goat or two and some dogs to guard the whole thing. They have their eggs going, meat for special occasions.

KL: What are the logistics of filming them? Do you speak Chinese well?

AG: You know, I speak decent Chinese, if I’m conducting an interview, I’d say at this point I understand about 90 per cent of what’s said. I can expect to understand 90 per cent of what’s said and I can express myself adequately. I still work through an interpreter because, that last ten per cent, you can’t be without it.

KL: How big is your team?

AG: Well up to this point, I’ve been going with basically a team of two. I’m just going with my girlfriend who has been interpreting for me and going around shooting myself. I’ve put together a perfect concept and I probably have enough material to make the film. What I’m now trying to do is get the funding to get myself maybe two Red Epics and a particular DP that I like and go back and basically shoot it now knowing the story beginning to end. Starting at Spring Festival as his children come back from school and spend Spring Festival on the road before they return to the home town where the grandparents watch them and going from there, in every location trying to get at least five days. I was thinking basically getting two to three days on the arrival and set up and two to three days on their departure and then do the same thing in the next city. Their life is pretty stable once their set up, the drama is in the move. That’s when anything that’s interesting is going to be taking place.

KL: So where do you look to for funding?

AG: I’ve been looking in Canada to the various cultural funds, which has been of some use, but, unfortunately, without a Canadian subject it doesn’t fall under a lot of the mandates. Having grown up in the film business in Canada and having worked there a good amount, I have some people I’ve taken it to over there and have been able to secure a bit more out of that. Now in China, I’m trying to find a number to round that off with. It’s the kind of thing, I’ve yet to determine if it’s possible to serialise it rather than it being a feature documentary that I’m making, I could sell it to a documentary station here as a six part miniseries because travelogues are always popular here, interesting people and interesting places and it’s related to food.

KL: So other than heading out to shoot what will you fill the rest of your time with?

AG: Well, various things. Right now, I’m putting together a TV show with Su [Zixu], it’s called Brunch with Su.

KL: Oh my God, tell me more about brunch with Su and then invite me to brunch with Su.

AG: One day I was speaking to Su and he invited me for brunch. I hadn’t seen him in awhile and I didn’t know brunch had become a big thing for him. I assumed it was some joke he was telling that I didn’t get. When I realised he was sincere in his brunch invitation, I went for brunch him, it was a great time and before coming here I’d been thinking of doing something to show the Beijing music scene off to a wider audience, outside of the city itself, domestically and also internationally. When you leave this country and tell people about what’s going on, they look at you as though you’ve drank the Cool Aid, gone mad and live in North Korea and don’t know it. So I’d been trying to think of a good vehicle for this project and I suddenly realised, Su! He’s got a great personality, great presence, he’s entertaining and he knows everyone.

KL: And everyone loves him.

AG: Yeah, you sit down, talk music, talk life with Su and record a couple of sets to break the thing up with and feature a couple of brunch spots to get our brunch for free.

KL: Have you made any yet?

AG: No, right now, I’ve got Su on-board and we’re looking to shoot our pilot on the 15th. I’m actually looking to lock down our first interview today. I’m cautiously optimistic. I thought Su and Da Wei would be a perfect opening. Everyone’s friends so it should be able to guilt people into doing things either way.

KL: Is it going to be purely local musicians?

AG: I want to mix it up with whoever is doing interesting things in the music scene right now so it will be foreigners, it will be Chinese, it will be mixes of things. I think separating the Beijing music scene into Chinese bands and foreign bands is stupid. The form itself has come from abroad and been adopted here in China and there’s a lot of bands nowadays doing their very own take on it and the foreign bands, I think, have been influenced by China just as much as the Chinese bands have been influenced by foreign form.

KL: So many of the bands are not purely one or the other now. There are people from all over.

AG: Exactly, that’s what’s so fucking wonderful about it.

KL: That’s excellent! I’m looking forward to watching Su.

AG: I’m also looking to do a small companion piece but if I’m going to tell you about that you will have to turn the recorder off.

And that is our enigmatic end. I know and you don’t. Keep watching Ari and you might find out.

NO VPN? TRY HERE: http://pan.baidu.com/s/1eSseDN

Ari Gunnarsson is a Canadian photographer and filmmaker living in China. He is a graduate of University of Kings College and McMaster University in Canada and has studied Chinese at Bejing Normal University. Gunnarsson has worked on film productions in India, Japan, Iceland and Canada, as cinematographer, camera assistant and second unit director. Chasing Spring is his first feature documentary.

Tan Siok Siok – Accelerating Serendipity

Photographer

Interview on April 26th at Beetle in a Box, Beixinqiao

KL: Please tell us a little about yourself.

SS: My name in Tan Siok Siok and my Chinese name is Chen Xixi, I’m ethnic Chinese from Singapore so a foreigner but I’m very fluent in both languages and I write professionally in both languages. The interesting thing about me is that the combination of things I do is very unusual. I am a documentary filmmaker but I also run an internet video company start up and then the photography part really came about quite accidentally. I had quite a full slate with the filmmaking and entrepreneurship and the photography came up about, a bit like you guys - you started to do what you wanted to do, and then it started attracting a lot more attention than I thought it ever would. The beginning of the photography is a funny story. I bought an iPhone much later than most of my friends. I bought it at the end of 2012 and before that I had a very simple Nokia phone. I joke that the phone will outlast me, I’ll be dead and the phone will still be running.

KL: Like cockroaches after the apocalypse?

SS: Yeah cockroaches and Nokia phones. So I bought an iPhone and I actually wanted to learn about mobiles and how they change our lifestyle because part of running a start-up is really understanding the trends and the best way to understand it is to use the stuff yourself. So I starting taking photos and my thought was really very simple, I've always wanted to make something every day but working in video and film it's very difficult, you can't make a video every day. On top of that, I'm running a company so I can't go very far away for long periods of time so I just had this idea that I should take a photo every day and share it. The sharing part was encouraging myself to keep doing it. I just assigned myself that every day when I get off the subway I walk into work, in those eight or ten minutes I take a bunch of photos, I post one. I think what was surprising was how quickly it caught on. About two months into doing it I already had people encouraging me to publish, encouraging me to hold an exhibition, and I've never really learned photography because when I used to work as a TV producer there was always someone else filming. They wouldn’t allow me to film because I’m not a professional videographer. So that was very interesting and I also noticed that my photos had a very specific aesthetic. I don’t know where it comes from, I’m just drawn to certain things.

KL: So that was initially surprising to actually look at your work and see that there was such a strong visual style?

SS: Given that I’m not trained in the fine arts. I’m not a painter, I’ve not really properly learned photography which is why iPhone is “what you see is what you get.” I’m trying to convey what I see so it went on for a while and there were some very touching incidents. This Indian film director who I used to work with when I was working at the Discovery Channel, he literally every five or six weeks when he sees a photo he really likes, he’ll leave a message on my facebook saying, “It’s time for the book.” It would be the same message over and over and over again. I went on for awhile just taking the photos mainly because I think within the context of my creative career, I already have a body of work as a filmmaker and I'm already running a company, there was no bid rush to publish a book. It was not like I'm new to this creative process and also sometimes it's all about timing as well. You know, people approach but it has to be the right collaboration and the right partner and all of that, and also, working in documentary, I have a very different sense of time. For me to work on something for three to five to seven years is perfectly normal. A lot about photography is showing up because it’s an accumulation over time. In terms of technique, when you take a photo every day you become good very quickly. It’s amazing because it really sharpens you when you keep practising and practising and practising. Then an iconic photograph is really a confluence of light, shadow, someone in the frame and you being there when it happens. It’s not repeatable. I’ve walked down the same street every day for three years now and the combinations do vary. One of the things I’ve really learned is it’s really a meditation on time, a passing of time and how every moment is unique. Just to give an example, yesterday I took some photos in front of my office and I walked down the street to see what else is there to took and when I walked back, within 15 or 20 minutes the light had changed.

KL: Is this the series that you just posted this morning?

SS: Yes.

KL: What I’ve noticed with your work in the way you use light and shadow is that you’re much more interested in strong contrast than a lot of photographers. I’ve seen often a flare of light then dark spaces that make them quite atmospheric. In those photos are sometimes very ordinary looking people but there is this extra intensity that’s lent to the photos because of that light.

SS: I think what informs the setting is partly because I’m a documentary filmmaker so a lot of my work, people often ask, “how do you take such photos?” because I take them with a phone and I think several things. One is the use of natural light. The reason why the time of day is important is because it’s when you take it and a very simple principle with phones or cameras is under good lighting conditions there’s not much that separates a phone camera or a much better camera. A lot of my photos use natural light and what is interesting about natural light is that people don’t realise it because they’re so used to editing the photos in post, natural light is much more dramatic than anything you can stage. I think that's why many of my photos are so focused on light and shadow and a very high contrast. The best street photography we know today, the classic ones, are all in black and white so there's a purity about it, there's a use of natural light. I think the other thing is because I'm a documentary maker, there's a lot of capturing. Essentially I'm just waiting for the moment to happen. And you can see the moving images influence because every time you see a series of photos I take, I've locked the frame and essentially I know when the person will walk into frame but I know where the best light is. Roughly it's usually when the person is to the right of me, in front of me. I'll take the first two just to focus so that I don't miss the person altogether but the third one is usually the good one. I feel that my photography is informed by documentary by capturing people in dynamic motion. It’s a funny story, it’s not easy to photograph people well and to convey emotion and I think the reason why is that you feel that ordinary people seem to have this additional quality in my photos because it’s emotion. It’s either anxiety or happiness. I think capturing the emotion when people are moving is actually a very difficult thing. This whole thing about taken the photographs for me was my daily practice. It's almost like sketching something every day so the interesting thing is that I will probably never give a photography talk, I'll probably only ever give a social media talk because I think that all that happens around the photography would not have happened without social media. If I had taken these photos and kept them at home for three years or five years, they’d still be good photos but none of all that has happened would have happened for it. I think posted it on social media is an important part of that creativity, creating a community around your work.

KL: So the social media aspect is just the regularity of the work?

SS: I post across multiple platforms: facebook, weChat Instagram, twitter but I think the important part is, to give a sense of the magnitude of it, since January last year these other things that have happened around my photography, I have had a friend help me organise an exhibition, that’s one thing, I had limited edition postcards released in partnership with the China Postal Service – official China Postal Service postcards – I had an installation in the hutongs that got a thousand people to send postcards to themselves or their friends, and I licensed a photo to be the cover of a Chinese novel, I was signed by one of the top literary publishing agents in China, I got two book deals, and they are both coming out this year. One is a collaboration with a novelist who happened to be writing a book of essays about his memories growing up in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, his name is Ning Kan [please check] and so that book I’ve finished the manuscript already. And there is my own photo book. Both are by top publishers, one is the top literary publisher in China, the equivalent of The New Yorker in China, the other is a top publisher of art, photography cinema books, also some very popular books as well and prior to this book they've only, as far as I know, published master photographers or famous directors. All that has happened because of social media. Why is that? It's because that thing about people following it every day. It becomes part of their daily routine and then out of 100 people one person will say, "This is really good. Can I help you make something happen?" And when the number of those people increase, then something big happens. One of the key things that happened was August 2014, one of the fans of the photos, there were stretches of time where he would just leave a comment every day and he'll re-post it to his weChat moments and he came to me and said, "Hey, let's do a crowd-funding campaign for your photos." So we took a couple of months with that and then we launched a crowd-funding campaign Januray last year. That was really what mobilised some of the people to hold an exhibition for me, people came the second day of the campaign, one of my friends and a fan of the photos brought her classmate and said, "I noticed in your crowd-funding campaign there was a reward that was postcards, my classmate works for China Postal Service so I think that she can help you release it with the China Postal Service." So it was all these things that when they happened it was like, Oh my God what's happening here?" All these people who have been working some of them don't even "like" your photos every day or comment, they suddenly came out of the woodwork to support it and the funny thing was that the campaign still failed. During that period was when the novelist noticed my photos and wanted to collaborate and I licensed a photo to be the cover of another novel. Despite all that the campaign failed mainly because of my inexperience. I think I didn't understand how crowd-funding worked in China where people were a lot more price conscious. I think we set too high a budget and people became wary, "Why is the budget so high?" Also, I think there were a lot of issued surrounding simple things like the mechanics of payment. It wasn't easy to pay for it. Also, people were waiting for other people to form the critical mass before jumping in. All this psychology, things that I didn't really know but by the end of that one month I was so happy because I just realised that within a month I have achieved what most photographers would take ten years to achieve. I've had an exhibition, I've got a deal with the postal service to release my postcards, I got a book deal with a novelist, I have licensed a photo to be the cover of a novel, in one month I did what most people take ten years to do. I think that is social media and the fact that essentially you’re developing community around your work and this community has varying degrees of engagement. Some people stay in the background but some people come forth and offer their resources and it’s a very powerful thing, that coming together of people.

SS: It’s also because by sharing your work online for free, you’re generating good will. That’s a question that comes up a lot, “Aren’t you afraid that people will steal your photographs or post them without attributing to you?” It's the last thing I worry about because I have friends who are very good professionals and they will often post online about people who use their photos without attribution and all that and I notice people posted my photos and re-posting my moments without attribution and I never call people out, I think the reason is because for most independent artists the key challenge is not piracy, it's actually obscurity so if people are starting to repurpose or appropriate your work it means that you have reach. It means for every one person who does that you probably have two or three people who would support you. I was giving this example that when I was doing the crowd-funding campaign we had these sample chapters and literally the selection of the photographs, they are quite a small size and would fit onto a thumb drive, the hundred photos would fit onto a thumb drive, the designer took the thumb drive and was joking with me, “I have your whole life’s work! I’m going to post them on the bridge or something or outside the subway!” And I said, “By all means because I have the community.” The value is not in the individual photos that get pilfered, the value is the community that has built around my work that will support me now and also for all the future work that I create. I think that’s the essential insight. That’s why I don’t mind because the community will follow my work and I’ve had that experience because I’ve also made independent films and they’re literary online now. People who have followed my work across the years, you know from the first film to the second film to the photographs and all that so I think the reason why social media is important, you build community around your work and they are your most ardent fans and patrons and some of them will go to great lengths to help you succeed. I always find it interesting, in China especially, the lurking phenomenon because I find that people when they first know me, the first couple of weeks they will "like" the photos quite actively, every day, every other day, especially if they are working on a project with me but then after awhile they will stop doing it but they are still following. For example, one week ago I went to Shanghai and then they will literary just start private messaging me asking, "Are you in Shanghai? I'm working at this school now, can you come and give a talk because I've been telling everyone at our school about you and how you should be on our committee for helping Chinese kids be more creative," so I get that quite often, suddenly they'll come out as my fan. I think the value of social media or blogging is consistency, it’s goodwill, the awareness that you’re building in this community. The interesting thing is, this is probably the second time it has happened to me that, because my identity was not that of an artist or a photographer because I started as a producer for television, so for me I have never elevated myself to the level of artist, it was my job, I was good at it, I worked for a big network and all that but the first time I realised that other people would think of me as an artist was the summer of 2012 in June, I suddenly got an email. The email was from the World Economic Forum Davos office in Switzerland. It read, “Dear Siok Siok,” it was very formal, “I’m so and so from the Davos office in Switzerland we’ve been following your work for a few years and we’d like to invite you to come speak at the World Economic Forum in Dalian,” they have one in September every year, “as part of our artists programme.” So that was the first I realised that other people think of me as an artist.

KL: So you were called out as an artist by the World Economic Forum before you’d even considered yourself one?

SS: Yeah because I was just doing what I wanted. I was just creating things that I felt had a reason to exist and then two days later, to confirm that the email wasn't part of my delusion, this very handsome young fellow showed up from Davos, he is the curator of the artist programme. He took me out to dinner in Sanlitun and invited me to speak at the summit in Davos and Dalian. So that was the first time. I think the second time that this has happened to me with the photography was that people now refer to me as a photographer, it's only this year that I would mention it as a footnote. If you look at my bio it doesn't mention photography in it because I didn't set out to become one and also, I think for me it was more just my latest endeavour, my latest attempt to solve a problem, to figure out something for myself. So I don't classify it as photography or literature or whatever but lately, people have started to call me a photographer. As opportunities have come up, I take them but if all of this dried up tomorrow I would still take photos.

I was signed by this agent, she’s a very top level agent in China and she was trying to introduce me to the publisher of that first book, the top literary publisher in China, and she said, “It would be good for you to meet him because he has asked me to because another novelist has insisted on using for photo for his cover,” but my response was, “That’s very nice but I’m not in a rush.” I think that’s the thing in China that surprises people, I’m not in a rush. It’s very odd when someone is not in a rush to be mega successful or very famous. I think people don’t understand that. I think we live in an era where everybody seems to be driven to become famous for no particular reason.

KL: On Loreli will are interviewing mainly emerging artists, some of them have big dreams, some of them have small, but the idea that is constantly drilled into them is that you need to have ambition and you need to seize on opportunities when they arise. Obviously, you are in a situation where you have had all of these opportunities handed to you without you seeking them, do you think that is purely luck or do you think that's the social media connection?

SS: I think social media accelerates serendipity so that in a way creates more good luck. That’s the function of social media but we need to understand that if your work is not any good or it doesn’t create resonance, there is nothing that social media can accelerate. I think the main thing for me is that I do think of myself as ambitious because I don’t have to do all these things because I already have a body of work, I’m already running a company, I don’t have to be a photographer on top of all that. The ambition I feel for me, first comes from the conviction that whatever I’m attempting to express has a reason to exist and it gives encouragement to some people. I’m not sure how many people because they are lurking. I think that to me is the premise of the work. I think where it differs is that I have a different sense of time. The emerging artists that you meet, I always get the sense that in China they think if it doesn’t happen in one year then it’s no good. The thing is for me, in some ways I am very confident so I’m not scared that it will go unnoticed because the very encouraging thing that I heard from the publisher of the photography book, he has published all these top photographers around the world, he said that, “Although so many photographs are produced every day because of the smart phone, there are very few good photographs. Haoshi haode pianzi zhen shao. So that’s the encouraging thing. It’s easier and easier to create work but the really god work is still very rare so I think on one level it’s confidence, commitment to the work, belief that if I do good work it will be noticed. You know of course I’m skillful at relating to people on social media, it’s not contradictory to being an artist, I think. Really simply, it will come, but it will not come because you are in a hurry.

Tan Siok Siok is a filmmaker, entrepreneur and a honorary geek with a deep passion for great storytelling in the age of real time web. Siok is an entrepreneur who has built Kinetic ONE, a social video platform in China with channels focused on youth culture, fashion and lifestyle as well as parenting & pregnancy. Siok previously worked as an executive producer for Discovery Channel in Asia,. The shows she produced have clinched more than a dozen awards and nominations at the Asian TV awards and the Golden Bell Awards.

Siok holds a Bachelor of Arts degree (Honors) in Comparative Literature from Brown University, USA.

Surzhana Radnaeva – From Pyramids, to the Steppe and Back to the Hutongs

Photographer

Tour of exhibition “Captured” on May 22nd at Zarah Café

SR: The first photo of the exhibition is a self-portrait. I would be always curious who is behind the camera or brush, behind any kind of creation actually. That's how I start the exhibition with a camera ready to capture things, people, buildings, forms, lines around me.

KL: Quite appropriate. There’s quite a lot of variety on your work. What we can see here is a lot of sculptural, architectural shots. With the diversity of what you do, what is it that you’re trying to capture?

SR: I’ve been always looking around since my childhood and would notice things like wind, rain, mood of people etc. that eventually grew into a love for photography. I don't make many projects or series, I'm more of an “eye-traveller” and I always have my camera with me and then when I see something that has to be captured - I do it. After a while, I look at my photos and see that there are connections between some of them that could go into series, so it's the other way around. I'm really in love with compositions, light, lines and forms and that's what you see in this hall mostly.

KL: You are largely led by the eye? When you see something you capture it and that leads to a variety of different styles through your work?

SR: Yes, most of the time led by the eye. Sometimes it’s not so easy to take a photo. I saw these stairs -name of the photo) for example and I really wanted to take a photo and I was walking around for a long time and then I went below the stairs, almost lying, and I found the right angle. The name of this photo [Vertigo] came to me right before exhibiting, I was looking at it and would feel some kind of a dizziness, a feeling of movement. Static movement. And yes - different styles form by themselves naturally.

KL: So you’re happy to take your time? You’re not like a street photographer, generally speaking, snapping as you go, you wait and you find the perfect composition?

SR: True, it takes sometimes a while to take just one shot, I like to take my time and find the ideal angle, I don't rush.

KL: Of all the photographers that I’ve interviewed, you are one of very few who name their works. So you think there is something important about naming the works?

SR: I don’t really like naming works as it gives some frame for the imagination but sometimes it is needed to hint, to show a way, because many people complain that the “artist makes whatever he wants and now I have to guess what he wanted to say." I believe that artists should explain something. Photography is the creation of the photographer. I have a real dilemma I still want to give some direction but also freedom for the imagination.

SR: This is Pyramid Triptych. These two pictures on the sides are inside of the pyramid. You can see the skin of the pyramid and how light is going through. In this one [Pyramid 2] I tried to capture rotation, like when you look up and spin you get this kind of feeling its like Sufi whirling.

Pyramid is my favourite work. It's very minimalistic triangle black form, but you feel so much in it: it's very strong, big and wise, you feel its power and protection. Here it’s really an ideal triangle right in the middle but I also like to break it like in Pyramid 2 to give it some freedom, give it some movement. Dance is a big part of me so you might notice the influence of it in my works. And as a little funny detail you can look up when you stand right in front of Pyramid and you will see another triangle in the roof, it was just a coincidence.

KL: This has got to be every photographer in Beijing’s favourite architectural subject. Do you find there’s pressure when you’re using a subject that has been photographed so prolifically to try to present it in a unique way?

SR: I never really care what people think, at least it wouldn't stop me from doing something that is important for me and I love this building. I spent four hours just walking around, getting lost in lines and enjoying Zaha Hadid’s creation. So the main answer is I don’t feel any pressure or competition with other photographers while taking photos. And also no matter how many times different people take photos of the same thing they always look different and give you different feelings.

KL: So you’ve got some portraiture in this room?

SR: I like to take portraits, but it turned out that in this exhibition not many of them. On this picture is Irene Sposetti - contact improvisation dancer and educator, I managed to capture a specific mood that I really like in this picture. And here is my friend Jing Jin, she is an artist and wonderful model, I have many good photos from our sessions.

This wall I call Zen Wall. It’s more of a reflection, observation of things, moods in a lighter scale.

KL: This wall feels distinctly more Chinese than the other work.

SR: Maybe the Zen mood, hutong and Jing Jin give this feeling.

Diagonal was taken in Moscow. I was walking and suddenly saw these birds flying and sitting on the wire like beads on a thread, I took out my camera fast, took this photo and felt relieved.

Sharp fragility - these needles are very sharp and dangerous, you can get poked by them, but they’re also really fragile, they have these little drops that couldeasily fall from a slight touch or wind. Everything has its fragility. That’s what I saw in this.

KL: So when you’ve hung them you’ve grouped them together into series? This one is your zen wall, you’ve got your geometry wall. What have we got here?

SR: This one is a mystery wall. I would say that this wall is really connected to my childhood. The first one [No name], I was always afraid of dark places, dark rooms without light and my imagination would play on its full volume. What do you see in that dark room behind the curtain?

KL: The matte printing makes that black space look even more inviting.

SR: Haha, true.

The photo in the middle was taken in my hometown. I’m from the Republic Buryatia in Russia. In Russia, we have 22 republics and Buryatia is on the border with Mongolia. We have the steppes around city and I went with my cousins to have a ride.

So when you don't know anything about this photo you might have many questions: Who are they? Where are they going? What have they done?

KL: That one is definitely enigmatic for sure and it looks a little be shady. Looks like they are up to no good.

SR: And it’s an open space. You can’t help but wonder why they would come here. You cannot also really hide anything in this wide open place, it makes a lot of questions. Actually, if you enter the picture and go to the left there was a huge cemetery, maybe that also affected the mood.

KL: So tell me about the bunch of bones.

SR: I grew up in the steppes with sheep. In the winter, we keep our sheep in big houses, really warm ones so they wouldn’t get cold. When you enter that place it really smells like warm wool and I would spend a lot of time every evening with sheep. In the steppes sometimes you might run into bones, and wolves used to attack sheep before, not anymore as all the wolves have disappeared now. For me it’s not really a dark picture, it’s just my childhood. Maybe for some people it’s kind of scary. It’s just about how different lives are of different people.

KL: So it’s just a case of decay where a whole lot of animals have died there?

SR: This picture is a part of an installation from one exhibition that I went to, it's not from steppes where I'm from, but it directly sent me to my memories.

KL: You’re right. It’s not a sinister picture at all.

SR: With this wall, a lot of people have told me, even though it’s colour, it is the coldest wall, maybe because of the blue, maybe because of the cold composition.

KL: The colour palette is definitely very muted and you seem to go for pattern and texture over the actual colour use.

SR: Yes. So when I take pictures in colour, I try to find something even more minimalistic than when I'm taking in black and white. Even if the frame is noisy I try to find the minimalistic part of the noisiness. If for example, there are many, many things so I just try to take a picture of these many, many things in order that they look just like texture. I like to play with these kinds of things.

KL: I particularly like this one. It’s so clinical and then you have this one odd blue chair. Tell me a little about it.

SR: This one I took on Lamma Island in Hong Kong, it’s at the pier. You can see that it’s not in the city, it’s in some weird place because behind the windows you don’t really see anything, it’s just fog or sky. Maybe some house in the sky flying or on the sea. I was really late for my train and for everything but I saw this picture and I thought, I have to take this picture. Didn't have any choice, so I took it and was happy and now it’s here.

KL: It definitely has a Kafkaesque waiting room in the clouds kind of feel.

SR: It gives a weird feeling, right? One of my friends had funny thoughts like this one here looks like R2-D2 [a rubbish bin] and it's trying to talk to his friend [the blue chair]. It’s funny.

KL: This one is just purely textural.

SR: It’s somewhere in the hutongs. I don’t usually make series but this one is from a series Landscapes. I take horizontal lines with different textures - an abstract landscape from different worlds.

KL: How many are in this series?

SR: For now, I have about ten.

KL: So you’re gradually building on it?

SR: Slowly, yes. I don’t know yet when the time will come to exhibit.

KL: And then the garlic cloves.

SR: That one I called Nature Morte. At the end of the exhibition, I wanted to add something with humour. It would also be relevant to the landscape series because of the horizontal lines but I’m not sure that it works.

KL: Again, there is almost no colour at all.

SR: You can see so many cloves of garlic with different shapes and lights so you don't need any more color in it anymore.

Also, some hutong people, you know, just dry their garlic on the floor and then they use it. I like it that they are so simple in this way. In Russia, we would never do that. We’d either wash it really hard or we wouldn’t dry it directly on the floor, we’d put something under it, newspaper or something…

KL: …and out in public where anyone could take it. There’s just that natural trust that no one will disrespect anyone else.

SR: It makes everything much more simple, it's nice. I'm for simplicity.

Surzhana was born in Ulan-Ude, republic Buryatia (Siberian part of Russia on the boarder with Mongolia). Until the age of 5 her home was vast steppes, later she lived in Moscow where she earned Art History bachelor, moved to Beijing in 2010. She takes analog photography, mostly black and white, in love with dance ( member of the group “Lunatic Moires”) and fashion design that all together effect her photography. She loves forms, compositions, lines, moods, light. In constant Search for beauty around her.

Exhibitions in China:

Solo exhibition at Zajia Lab Project, 2012

In 2014 had an exhibition in Russian Cultural Center

In 2014 May exhibition in Beijing Polytechnical University

To see more photos: www.surzhana.com

To contact: surzhana@hotmail.com

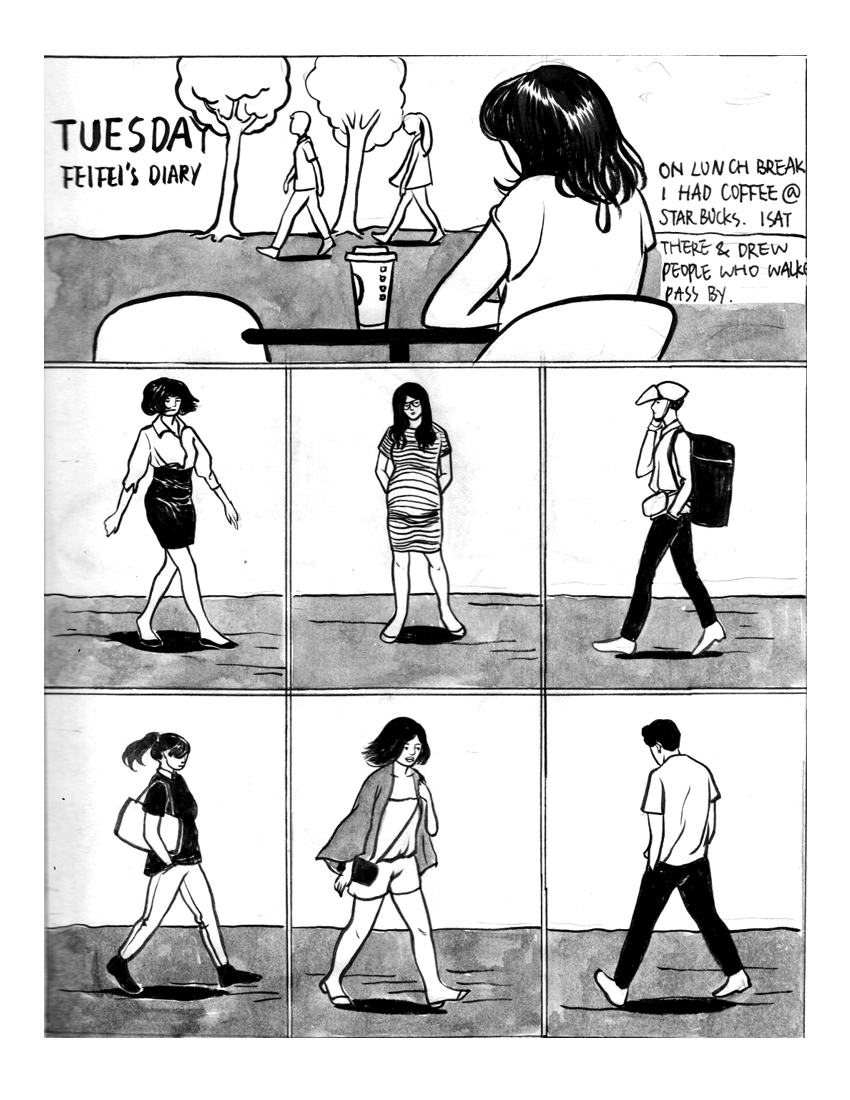

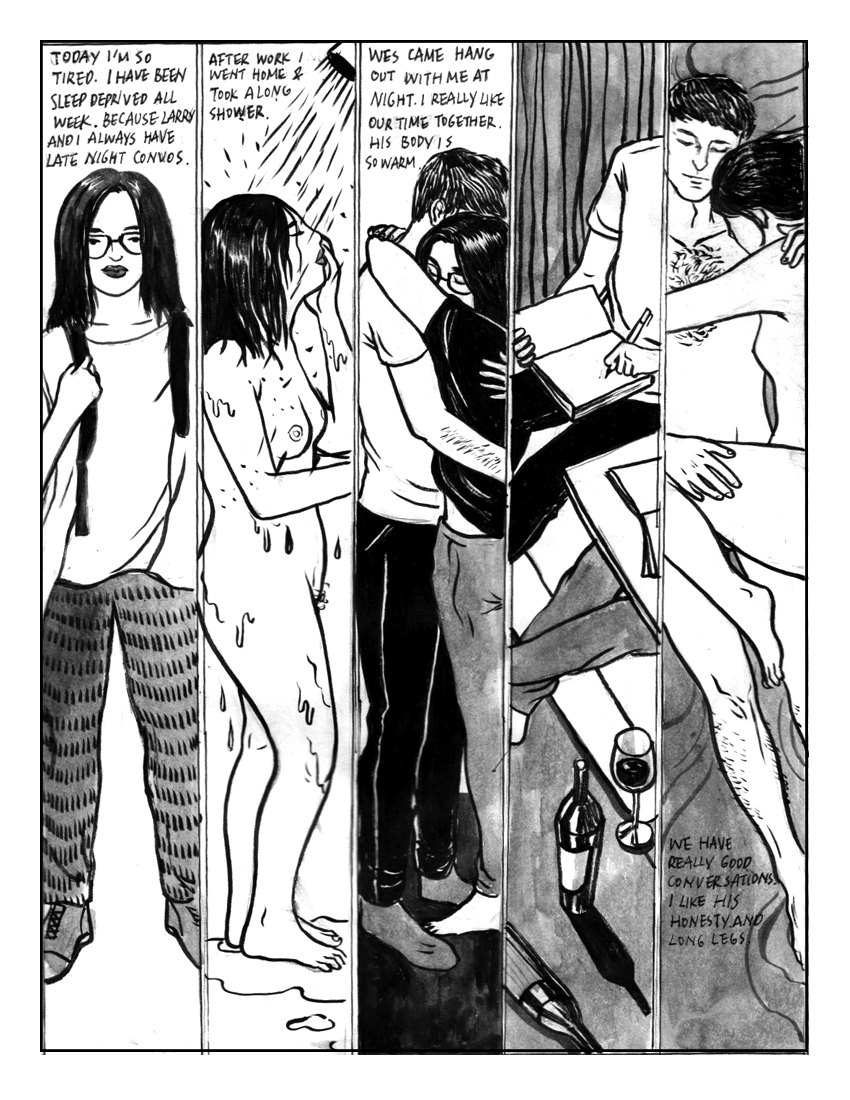

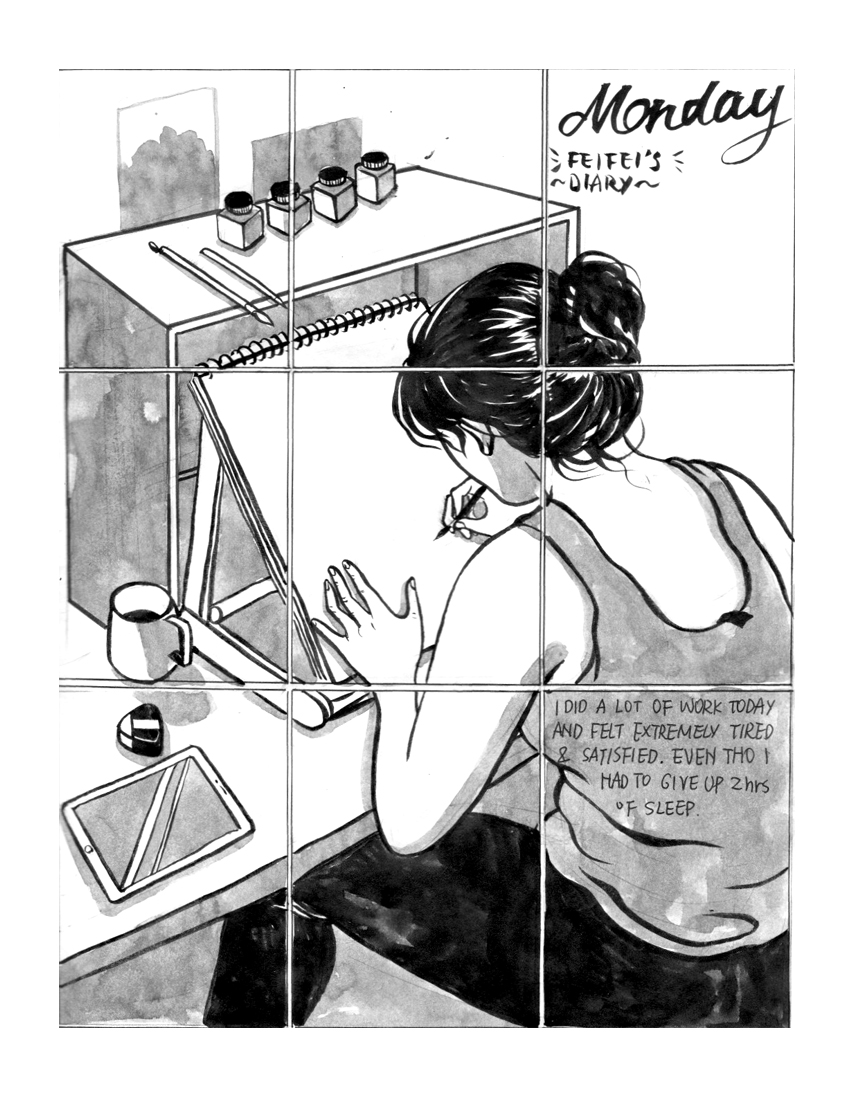

FEI FEI - Creative Block becomes a Redwood

Illustrator

Interview with Loreli's newest curator, Angela Li, via email June 7th 2016

AL: A lot of your illustrations have a very charming ‘slice of life’ appeal. How do you go about making those moments seem organic and authentic on paper?

FF: Mainly for two reasons. 1, I make drawings about me and my life. And I embrace the imperfections both in my brush stroke and life. 2, I use a brush or brush pen to draw, the tool itself gives off an organic feel.

AL: 你一部分的插画有种‘我的日常生活’的色彩,很吸引人。你是怎样在你的画里让这些片段保存它们的真实感呢?

FF: 有两个层面。第一个是我画的是我自己和我的生活,我会拥抱我生活中和我的作品中的不完美。第二是我选择用刷头笔来画画,从而使我的画有一种很生活化的感觉。

AL:You have made a series of women of different ethnicities generally in traditional costume yet the flowers in these works contain the most Chinese calligraphy influenced brushwork that I've seen in your pictures. How does this series reflect your ideas of gender and your own sense of identity?

FF: I have been thinking about the definition of gender a lot since I took a women’s studies course during undergrad. I had a lot of trouble identifying myself with “woman” growing up. And it wasn’t until recent years that I learned to appreciate femininity and women’s power in general. Through this series of portraits I aimed to express my affection and admiration towards femininity. These portraits are based on a group of close friends of mine. I just wanted to show how beautiful and powerful they are to me despite their own opinions on themselves. So I added a lot of fantasy elements to them. In the process of making these, I’m fueled with energy and warmth because it takes beauty to see beauty.

AL: 你有一系列画专门展示不同穿戴传统服饰,不同种族的女人。这些画里的花的画法有着很强烈的中国书法元素,超出了你所有其他的组品。这个作品系列如何表现着你对你自己和你的性别的认知呢?

FF: 关于性别的意义和含义,我想了很久。我在读本科时曾上了一个女性学的课。在我长大期间无法完全和我的性别,或“女人”,产生共鸣。直到不久之前我才学会如何去欣赏女性的一些特质和强大的精神。我希望可以通过这一系列的人像来表示我对女性的爱和欣赏。我的一些好朋友们是这些画像的原型。我想要展示他们自己有时都意识不到的美和精神。我在画里加入了一些奇幻元素。在创作这个系列的时候,我所看到的美让我身体里充满着温暖和能量。我的美使我在其他人身上看到美。

AL: Let’s talk about this piece of work:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BFtTSofvUme/?taken-by=feifeiart

There’s a trend on the #interwebz nowadays celebrating self-deprecation and the broadcasting of a purge of intense emotions by an individual. How do you relate to this? is there an equilibrium between finding catharsis for yourself and jabbing at the absurd norms to which we’re subjected?

FF: I think self-deprecation is both inevitable and manageable. The reason I made this zine is because I want to stay true to myself, and my audience. My mother suffers from severe depression and it had affected me more than I’m aware. On one hand, I’m very content and have a good control on my emotions. On the other hand, when I feel depressed, it always seems to hit me heavier than happiness. Some days I will feel paralyzed and stay in bed all day and drop all plans. And the only way for me to “talk” myself out of it is to stare straight at it by illustrating it. Only then, “I” will have nowhere to hide. I think make art about depression is important. I always try to be humorous about it too.

AL: 我们聊聊这个作品吧:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BFtTSofvUme/?taken-by=feifeiart

现在自贬和在网络上把自己最深的情绪表达出来似乎已经变成了一种潮流。你对这个怎么看呢?在为自己找到情绪的发泄和嘲讽现在社会里一些荒谬的准则两者中有平衡吗?

FF: 我觉得自贬是不可避免但也可被操纵的。我做这个zine的初衷是想不背叛真实的我和喜欢我的艺术的人。我妈妈有严重的忧郁症;这个对我的影响比我想象的还要强大。有时候,我感觉很满足,我可以控制自己的情绪。而有时,当我忧郁的时候,那种感觉总是比快乐带给我的影响我深很多。有时候我觉得自己瘫痪了,我会抛掉一天的事儿,自己躺在床上。唯一一个可以把自己“带出来”的方法就是正视它,把它画出来。只有这样我才能无处可逃。我觉得通过艺术表达自己的犹豫是有意义的。我也喜欢用幽默的方式表达它。

AL: How was your experience studying art in Connecticut? Do you think art is taught differently due to geographical differences?

FF: My college education basically shaped how I am right now as a person and artist. I had some of the best mentors and artist friends one can ask for in life. The program had taught me the tools of becoming an artist. I have never studied art on a college level in China so I can’t make a fair comparison. But from what I have seen, I think art is taught differently for sure. It’s not just art though. It’s more about the mindset that one brings to art making. From personal experience, I spent half of my college unlearning, undoing what I was taught in China, in order to take in new information.

AL: 你在 Connecticut 学画是一种怎样的经历?你觉得在不同的地方,艺术教学有什么区别吗?

FF: 我的大学经历直接的影响着我,不管是作为一个人还是作为一个艺术家。我在那里遇到了我这辈子几个最棒的导师和志同道合的朋友。在哪里我学到了作为一个艺术家所需要的技能。我从来没在中国在这个层面上学艺术,所以我不能正确的衡量他们的区别。但从我所知道的来讲,艺术课程在这两个地方有很大的区别。这不只局限于艺术,其实根本的是在艺术方面的思维方式。从我的经验来讲,我大学的一大部分都用来忘记我所学到的,丢掉我在中国学到的东西,去接受新的东西。

AL: Your project, Fei Fei’s Diary, manages to capture some very raw moments in your life - it’s certainly more than an Instagram-esque documentation of your day-to-day experiences. What’s the story here? How did it come about?

FF: The story began with that one time when I was depressed and had a creative block. I wanted to commit to a project that runs longer than a day. And I want to make something contemporary and relevant to my life. I was obsessed with Sequential the app, buying and reading graphic novels all day long. I stumbled upon Noah Van Sciver’s More Mundane and was so inspired by it. It’s a diary filled with not-so-well-drawn-drawings. It made me realized that I won’t get better by waiting to make a book, I will get better by making and finishing a book. I was so empowered because I realized that I could make art with the skills I got right now, right here. So I started to draw diaries in my sketchbook, and I did get better with craft and story telling skills. Due to the nature of it, I want to replicate my days as real as possible, so I rarely make up anything, but I did change some of the names though, to protect their identities..

AL: 你的作品, “Fei Fei’s Diary”,完整的捕捉了你生活中一些很真实很原始的时刻 – 它没有运用Instagram上那种以流水账的方式去记录生活。这个的由来是什么呢?有什么故事吗?

FF: 故事的开始是有一次我感到挺犹豫的,遇到了灵感障碍。我想把自己投入到一个能做的比一天长的一个组品,一个比较现代,跟我的生活有关联的作品。我当时Sequential (一个app) 特别上瘾,整天在那上面看漫画小说。我无意中发现了 Noah Van Sciver 的 More Mundane (日常),让我有了很多灵感。More Mundane 以日记的方式展示他的很多不是很完美的画。这让我发现我不能一直等着我画的更好的时候再去做一本书。反而,我可以通过从头到尾画一本书来让我画得更好。我突然充满了很多力量和自信。我发现了以我现在的能力,我已经在这一刻就可以做自己的艺术了。然后我就开始在我的画本里画日记,我真的一点点学会了如何去更好的去画,去讲一个故事。因为这个东西是个日记,我想让它真实的反映我的每一天,所以我也很少会加虚构的元素进去。我倒是改过故事里的一些人名,来保护朋友的隐私。

AL: I for one think that presenting the raw form of an event in your life to an audience takes a lot of balls. Do you relate to that at all with this project, and if so how?

FF: Thank you, I think it is a very important question to ask. It does take a lot of courage to fully expose my life in such detail. But I think that’s the beauty of art. As soon as the ink hits the paper, the character no longer belongs to me. It belongs to the audience and the void. When I draw myself out, it’s not “me” anymore. It’s some twenty-something-girl who lives in a metropolitan. And my role is to document and illustrate the things happen in her life. I used to be self-conscious and full of self-deprecation. I was so scared of what people might say when I draw myself in different stories. I feared the judgments. But surprisingly, I got 100% positive feedback from my readers. They appreciate my honesty in storytelling and the ability to expose emotional vulnerability. I don’t want to hide anymore. I choose to not feel guilty about who I am and what I do. I choose to be honest and true to myself. I found out that the “fear” in me was caused by ego, not me. My ego is always judgmental, mean, fearful, and harmful to my mental health. By going the ego’s opposite way, I’m taking over the power by exposing my fear (ego). Therefore free myself from it.

AL: 我觉得以这种方式在别人面前展现自己的日常挺胆儿大的。你做这个作品的时候有这种感觉吗?

FF: 谢谢,我觉得这个问题应该被回答。去以这种方式展示我生活中的一些细节确实需要一些勇气,但我觉得这也是艺术的美。当墨碰到纸时,这个人物就已经不是我的了。它是虚空中的,也是所有看它的人的。当然在纸上画出我的时候,我就已经不是“我”了,而是一个大城市里二十左右的女孩儿。我所做的只是去记录和描述这个女孩儿的生活。我以前挺缺乏自信的。我很怕别人对我在不同故事里画自己有各种的意见。我害怕他们可能会说什么。让我挺惊喜的是一直到现在我只从读者那里得到了正面的反馈。他们喜欢我故事里的真实和我毫无保留的表现自己情感上脆弱的一面。我不想再躲避了。我选择不去为自己的所作所为而解释。我认识到我身体里所谓的恐惧完全来自我的自负。我的自我总是苛刻的,刻薄的,害怕的 – 这一系列的情感都在伤害我的精神健康。一旦我跟它分道扬镳,一旦我展现出我的恐惧和自我,我其实就占了上风。然后我就彻底自由了。

AL: You manage to blend the raw and the naiveté into visual stories that could otherwise be mundane. How did you find this voice?

FF: I’m glad you can find a voice in my work. Maybe I’m too close to it to realize my voice. I think you just summed up me. I’m a mix of raw and naivete. I love my fellow homo sapiens. (is that a weird thing to say?) Truly, I love humans, as a species, I adore them like s’mores on a stick. I just want to hug every human and tell them how beautiful they are. The stories I make are the way they are, because my work is always a reflection of my environment and me. When you draw mundane, it will no longer be mundane. Like Andy Wahol’s soup can on a canvas.

AL: 你通过融入露骨,原始的一面和纯真的一面把原本“日常”,平淡的东西变成了你现在所创作的视觉故事。你是怎么找到你自己的声音的呢?

FF: 我很开心你可以在我的作品当中察觉的我的声音。可能因为我跟这个东西太亲密了,我都无法指出我自己的声音是什么。我觉得你刚才完整的概括了我。我很爱我的同类,我的人类们(这样说挺奇怪的的吧?)真的,我爱人类这个物种,像我爱拿着一个串烤S’mores一样。我想拥抱每一个人,然后告诉他们他们有多美。我的故事就是我身边的人,因为我的作品总是反映着我所在的环境和我自己。当你画出“日常”时,它就已经不只是无聊,不只是空虚的了。就像Andy Warhol的金宝汤罐头一样。

AL: How did you find your artistic style and medium? Especially the visual novel format on which your Diary project is based.

FF: Although I’m very experimental, my primary tool has always been ink. I struggled with it for a long time in college, because I was eager to try something new. I tried micron pens from 005 to 3, acrylic painting, and mechanical pencil, etc. I always go back to ink. Maybe it’s because I studied Chinese calligraphy for 3 years when I was in elementary school. I guess the influence never left me. In the diaries I choose ink as the primary medium is because I need something definite and quick. I can’t afford to spend 2 days to color it with paint. I need something bold.

AL: 你是如何找到你的风格和你的平台的呢?尤其像你的 Diary 作品里的视觉故事这种方式?

FF: 虽然我非常喜欢实验各种东西,我一直以来用的最多的工具还是墨水笔。我在大学时跟墨水笔有点儿波折,因为我当时特别想试试其他的东西。从005到3的 micron pens到亚克力,再到自动铅笔,我都试过了。但是我总是回到用墨水。可能是因为我在小学时学了三年书法,一直影响着我到现在吧。我的diary主要采用了墨水,因为我需要快和准。我没办法花两天的时间去用颜料上色。我需要能跳出来的东西。

AL: Your Insta description says “full-time illustrator, part-time alien.” Does one serve the other? How are those two identities balanced?

FF: Yes. I often get this feeling that I’m not from this planet. So I find my surrounding very intriguing. I enjoy being an observer and outsider. That definitely helps my illustrations because I’m sensitive to visual details.

AL: 你在你的Instagram上说你是“全职插画家,兼职外星人”。这两个是互相衬托的吗?这两个身份如何共存呢?

FF: 是的。我经常会觉得我不是来自地球的。我觉得我周围的食物很有意思。我喜欢做一个观察者,我对视觉细节很敏感。这一点对我的画起到了很大的帮助。

AL: Anything else you wanna say?

FF: I want to be a redwood when I grow up.

AL: 你有什么其它想说的吗?

FF: 我长大以后想做一颗红衫

FEI FEI with her co workers, she is the one in yellow.

FEI FEI (b. 1993, China) makes drawings, prints and mixed media artworks. By documenting her daily life in the on-going visual diary series, FEI FEI tries to understand and articulate her life as a twenty-something contemporary Chinese female artist. Her work deals with identity, sexuality and the active effort of being present. FEI FEI’s work has been exhibited mainly in the US, including The Museum of American Illustration (NYC) and Benton Museum of Art (CT). When she’s not drawing, she finds comfort in reading sad memes on Instagram.

GIANT - Graffiti Artist

An interview with Nate Rood for Loreli at The Neighborhood Meeting - Do the Write Thing on May 14th 2016.

KAYO - grafitti artist

An interview with Andrew Smith for Loreli

A series of interviews with graffiti artists who attended:

LOOK ARCHIVE

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.