Posts from December 2015.

Essay Contest Winner: Sophie Haas

Posted Dec 27, 2015

Our first annual writing contest had 15 submissions of a motley of topics, some closer to the prompt than others, but all fascinating to read. The panel of judges had a tough time choosing winners, and after much deliberation, one man and one woman of letters arose from the sands. This week, we'll share the essay of Sophie Haas, former Beijinger and current Hangzhou resident.

How did you decide on this topic in particular for the indulgence essay contest?

I read the topic and thought I had nothing much to say about indulgence. Then I had a three-hour, what-are-we-doing-here-in-China conversation with a good expat friend in Hangzhou. She helped put into words a lot of thoughts that had been running through my head, and something sparked.

What was the process of writing it like?

For a while, I just really had a lot to say about my experience being white in China and not a whole lot about indulgence (oops.) So I did what writing teachers have always told me to do -- I wrote out everything that was running through my head and then left it alone for about a week. I usually can't do this because I procrastinate too much. During that simmering process I started to get a better idea of how I could tie everything together (although there's a lot more I'd like to do with it now!)

How badly do you wish you could have been in Beijing to go to the party?

I CAN'T TALK ABOUT IT.

Also...

China Timeline?

I got here three and a half years ago, and I think this year will probably be my last one. Kind of like China College.

Three words to describe your time in China so far?

Confusing, incredible, delicious

Most memorable moment from my first year in China?

A conversation with a taxi driver in Nanjing about the Sandy Hook shooting in Newton, Connecticut, in which I realized that I didn't even know how to begin asking him the right questions, let alone make sense of the answers (and I'm not just talking about language.)

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life?

Junior year of college, and also this year.

My writing history?

I mostly like to write poetry, and it's the only form of creative writing that I studied seriously in college. But I love nonfiction, and that seems to be what I'm most drawn to these days. I'm trying to get more disciplined about writing--I'm really lazy and I often only write when I feel like a thought is being yanked out of me. Shockingly, this doesn't lead to an abundance of writing practice.

Favorite word to use in writing?

Don't have a favorite word, but I like the semicolon way too much.

One word to describe the process of writing?

Endless.

And now, Ladies and Gentlemen...

Death by White Chocolate

The realization struck on my very first day in China, when I was 17: during the 14-hour plane trip from New York, I had somehow become a tourist attraction. I’d landed in Beijing the night before, and my host family had decided the way to welcome me to China was a sunrise trip to Tiananmen Square to watch the raising of the flag. Apart from eating a cucumber and drinking overly sweet green tea from a bottle, I hardly remember anything about that day or Tiananmen itself. But one memory has always stood out as clearly as if it happened yesterday: many, many people wanted either to take my picture or to have their picture taken with me. At first I tried to refuse, but soon I started to get into it, putting a friendly arm around someone’s daughter or copying the peace sign that everyone else seemed to be making in pictures. I’d be lying if I said that I wasn’t flattered, or that I really minded the picture taking. I’d never been considered exotic in my life and that day I began to understand what it was to feel like a model.

This was back in 2007, pre-Olympics, when foreigner sightings generated more excitement than they do today—particularly for Chinese tourists from outside of Beijing. Yet I am surprised by how often something similar still happens to me, eight years later, almost on a daily basis. Parents want pictures of me with their children. Über drivers snap selfies with me. And most people want not only to know where I’m from but also to tell me that I am beautiful. I am told this by cab drivers, by teachers at the school where I work. It happens in grocery stores and from both men and women alike, sometimes even from my students. At this point, I’ve almost come to expect it, and I’m ready with my standard answer of, “No, no, you’re too kind.”

Let’s clear one thing up right away: this phenomenon is limited to my life in China. I am no Kate Moss. I would describe myself as attractive, but not in a particularly striking way. I have wavy light brown hair and blue eyes, and I am of average height. I think that sometimes when they say “beautiful” what people really mean is “different”—indeed, I do not look Chinese. But there’s something else at play, too: it’s that I’m extremely pale, one of those people for whom the beach, with its endless applications of sunscreen, is more work than fun. White skin is prized in China to the extent that most skin lotions contain bleach — an ideal that my American self (let’s celebrate everyone!) will never understand. As a boyfriend once put it to me, after two women had approached us in a restaurant to comment on my looks, “Of course I think you’re beautiful. But to Chinese people, because you’re so pale, it’s like you’re especially beautiful.”

I wish I could say that this attention was limited to aesthetics. But do we treat people differently when we find them beautiful? I still remember what my tenth grade English teacher had to say about this when we read The Great Gatsby: “Everyone likes Daisy because ‘she’s so pretty.’ But she’s horrible!” Of course, I don’t want to be horrible.

But last year, when I was living in Beijing, I went over to China Unicom during lunch one day to figure out why my cellphone wasn’t working. My spoken Chinese is pretty decent but reading characters is much harder for me, and I struggle to read the texts from my cell phone company. The store was packed (totally typical at lunch time), so I took a shortcut. I found a frazzled employee and asked if he would read the texts and diagnose the situation. I then told him that I couldn’t use the machine that he directed me to (it was in Chinese). The man ended up cutting about twenty people in front of me in the line in order to do it for me. When I got back to the office a mere fifteen minutes later, my friend C, who is Chinese by birth but moved to America at the age of nine, was surprised to see me so soon. He’d warned me that given the lunchtime crowds it could take a while. “How did you get back so fast?” he asked me. “Oh, they helped me,” I said vaguely. C shot me a dark look. “You mean you asked them to do it for you.” Well, when you got down to it, yes. “I hate that,” he said. “Hate what?” I was confused. If anything, I thought he’d be pleased with the success of my little adventure. After all, he and I spent quite a lot of time complaining about the helplessness of our non-Chinese speaking colleagues when it came to dealing with things like cellphones and train tickets. “They just let you cut the line because you’re white,” he said, shaking his head in disgust and turning back to his computer. “And you can even speak Chinese! You could have done it yourself. That’s so unfair.”

He’s right about that, of course. I was given special treatment because I am a foreigner, and white at that. To me, the concept of indulgence has always been laced with caution—indulgent is something you’d only want in small quantities. Chocolate that’s delicious in the first two bites, and nauseating by the fifth. Perfume that smells great in the store but makes your head spin after three hours of wearing it. But in the best and worst sense of the word, my existence in China, as an expat, is in many ways an indulgence. I chose to come here, and I make enough money to have enjoy nice things here. I feel safe here. And much of the time, I am granted special treatment based on my looks. Many, many things are made easier for me here. If I don’t want to write down my order in a restaurant, the waitress will write it down for me. Could I take the time to look up the characters on my phone and write them down myself? Of course. But why would I do that when it’s so much easier to ask the waitress to do it? Why would I try and call the airline on the phone when it’s so much easier to say, Oh my Chinese isn’t good, can you do it for me? Because here’s what happens when you are treated vaguely like royalty: you start to think that the regular rules don’t apply to you. It is indulgence gone truly rancid.

The problem, of course, is that I didn’t fall in this trap right away. I only became truly aware of how much I was abusing my whiteness one day when I decided that I didn’t need to show my ticket to an airport employee as I left the baggage claim so she could check my luggage stub, which is a requirement for all passengers. First I pretended that I didn’t hear her and then that I didn’t speak Chinese. I was eventually apprehended by a guard and forced to take my slip out of my pocket and show it to the very disgruntled employee, a woman of about my mother’s age. As I left, she shook her head disapprovingly and said aloud, “Can you believe that? She thought she didn’t have to follow the rules just because she’s a foreigner!” It was, unfortunately, a completely accurate assessment of the situation. I’m not sure which is worse—white privilege as an invisible backpack, which you constantly abuse unknowingly, or white privilege that you are far too aware of and use to your advantage. The one thing I do know is that being considered beautiful should never be license to behave like an asshole. Look no further than Daisy Buchanan.

Perhaps I feel that I “need” my privilege. The fact is that most of the time China is difficult for foreigners to navigate. Nobody “picks up” Chinese. Even reading a newspaper requires years and years of intense studying. Things happen every day here that are hard for me to understand, from the way my Chinese colleagues approach problem solving to paying my electricity bill, or figuring out which line I should stand in at the train station. Since I read at an elementary level, these things seem even harder to navigate — and I know that for those with less Chinese, it’s even more difficult. Sometimes I feel that I cave to the temptation of getting special treatment despite my best intentions because without it, I often feel like I’m walking around blindfolded. I think I can make out shapes and outlines through the blindfold, but half the time I’m not sure if what I’m seeing is real or just the insides my eyelids. Being a foreigner in China is never boring, sure. But exhausting? Always.

I’m not sure that there is any way to let go of this indulgence completely. But perhaps the most I can do is try to follow the rules, try not to cut lines that I don’t need to cut, push myself to write the characters and buy my own train tickets. The history playing itself out in America precedes us: we should all know better by now than to claim ignorance of how our skin color changes things. But most of all, I think I’m afraid of what will happen to me if I don’t. It’s not that different from fancy chocolate, after all: you don’t want to get sick.

Creative Non-Fiction by Nick Compton, posted Dec 18, 2015.

Best Friends

by Nick Compton

Jake’s house wasn’t much to look at. He rented a weather-blasted two bedroom on the edge of town for a couple hundred bucks a month. The roof was caving in and the exterior scraped clean of its white paint by winter winds and too little attention. What remained was gray lumber streaked white by curling chips. It looked mean. Haunted, almost.

He was my best friend growing up, but I didn’t know where we stood now. I’d left for university, moved around, ended up working in China and never really looked back. It was rural America. A tiny town in the hills of Northeast Iowa. My home, but no place I wanted to stay.

I pulled my car into his driveway and parked next to a shed filled with split wood. It was my first extended time back in three years, and I was stunned by the raw beauty after the blurry sameness of Beijing. Unlike the rest of the state, this corner of Iowa wasn’t covered by glaciers in the last ice age. Because of this, the terrain remained unpolished, rugged and hilly; laced with trout streams, soaring bluffs, and deep hollows. The culture in the area developed accordingly. In these hills, generations lived off the same land, raising huge families and forming blood bonds and clan extensions that wouldn’t be out of place in the back woods of Appalachia.

Jake’s house was settled onto an old-growth prairie hill, and behind it, stretching for miles, was rolling forest cut by small acreage corn fields. As I walked to his side door carrying a case of Coors Light, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the scenery. In Beijing, for so long, I’d hungered for this wildness.

I walked in without knocking. His porch was flooded with crushed beer cans andempty whiskey bottles. I saw him sitting at his kitchen table sipping a beer and tapping on his smart phone.

“Niiick,” he said, getting up to shake my hand. “How you been, bud?” He cracked the same smile he had when we were 12.

“Hey man,” I said, shaking his hand and smiling. “Been good, brought you some more silver bullets.”

He laughed. “Well good. That’s the only shit I drink now, can you set it by the fridge?”

Earlier, I’d stood in a grocery store beer aisle for 10 minutes trying to decide what to bring. Finally, I looked at his Facebook page and saw pictures of him drinking a Coors Light. I decided it was a safe bet.

I popped open a can as I set down the case and took a good look at him. Aside from a few added piercings and a tattoo of something that looked like an eagle on his neck, he hadn’t changed. I’d always envied his eyes, which seemed to have the magical quality of melting a girl clear down to her panties in a matter of minutes. Even when he was drunk they were bright brown and sturdy. The eyes of a man you could trust.

I pulled out a chair at the table across from him and we both sat in silence for a few seconds. His kitchen was dark and humid, empty pizza boxes strewn across the room and his counters stacked with dirty plates. He didn’t have an air conditioner and the early summer air was already heavy and stale. The smell reminded me of my high school wrestling room.

“You had dinner?” I said, pulling for conversation.

“Yeah, mom dropped off a casserole,” he said. When we were kids, his parents were still together, but as we drifted apart in high school, they got divorced and his dad remarried. His mom gained a wild streak, multiple boyfriends and a near permanent stool at the town tavern. I could tell it hurt him, but she was good about things like this. Dropping off leftovers and helping out with bar tabs.

“God it’s probably been four years since we seen each other, ain’t it?” He said, shaking his head at the notion. “What’s it like over there, you got a girlfriend?”

I thought for a second. “It ain’t like here, man,” I said, incapable, somehow, of explaining. “I do have a girlfriend. Met her in school in Beijing. She’s from the Philippines.”

He nodded his head, taking it in.

“How about you?” I asked, “Girlfriend? You still welding?”

“Na, I’m through with that shit, man,” he said. “Been single going on a year, but it’s been bad. Pretty much a non-stop party.”

I understood. “What about a job?”

Jake, like most people back home, graduated from high school and found work with his hands. He learned to weld and last I knew he was commuting 30 miles every day to a company that worked with sheet metal.

“Had to quit,” he said. “Coming back from Manchester smoked one night and flipped my car. I snuck away and called your dad, but the cops found it the next morning and took my license.”

My dad was the town lawyer, and I respected him for not telling me things like this.

“Christ. You were drunk?”

“God I was smoked,” he said, laughing. “Started drinking at 10 that morning and road tripped to Cedar Rapids. From there I don’t remember what happened, but I knew my car was fucked.”

I asked him where he worked now, and he said he was doing part time installing car stereos in a dumpy little building behind a shuttered gas station.

“Stuffy as hell in here.” He said. “Wanna sit outside, got a side stoop that’s alright.”

We grabbed the case and moved to the stoop. The sun was beginning to sink, and the sky was streaked pink and purple. The horizon stretched on forever and I could smell blade-cut grass.

“Man I missed this,” I said as we sat down and popped fresh cans. “I been a lot of places, but there aren’t many prettier than this.”

Jake smiled and took a loud gulp of beer. “Yeah, it’s pretty out here, but goddamn there ain’t shit to do.”

“I hear that.” I said, “What about crystal? Still all over?”

In the mid-90’s when I was just a kid, meth roared into our community with the force of an F-5 tornado. The farm economy was on the downspin and many locals had lost their hats to giant ag processers gobbling up their land at cut-rate prices. We were rural and poor and desperate for something. For as long as I could remember, an ocean of Busch Light filled up those holes, but when meth came, it was different. It tore up families and shattered good people. We all had neighbors, brothers, friends or colleagues who were involved.

It was a stain on our community, and with our Midwest sensibilities, we winced at the thought of talking about it head on. When we had to, we talked sideways, in low tones. It was a problem, we knew, but it was our problem. We would fix it. When a big city reporter came to write a book called Methland about the situation in our area , he couldn’t score an interview in Strawberry Point. He wasn’t one of us. We weren’t talking.

“Aw hell, that ain’t changed,” Jake said. “You wouldn’t believe how much of it is out there. It’s only getting worse.”

In college, I’d caught rumors floating around that Jake blew smoke. In a sense, I couldn’t blame him. If you were single and young, with no prospects or way out, the isolation and monotony of Middle America had a way of crushing you. You looked for something, anything, to break the depression.

“I seen a helluva lot of it, but I never touched the stuff,” he said, maybe a little too defensively.

I peered at the horizon and nodded solemnly. We threw our drained cans next to a cooler and popped our next ones. Since I was in high school, the dri nking habits I’d known at home had carried a breathable sense of destruction. Here, you drank enormously and quickly with the singular dark goal of getting fucked up. We satat the bar or in our cars cruising the gravel roads, pounding cans of cheap beer to crush the boredom and chase away whatever demons we couldn’t name and didn’t dare speak out loud.

For a stretch, neither of us said anything. In a field below, we could see a big orange doe and two young fawns lazily eating corn shoots. The cicadas and crickets chirped in a frenzied pitch.

“How about your family?” Jake asked. I answered politely, sugarcoating the drama and fuck-ups like we all do, and asked about his. He told me his dad was still married, two more kids. His younger brother, forever five in my mind, had knocked up a 20 year old when he was 15. He was raising the kid and working construction. His sister cut hair on the highway and lived with a soybean farmer.

We continued to drink and make small talk about mutual friends and college sports. Jake pulled out a pouch of plug tobacco and asked me if I wanted a dip. I declined, he said suit yourself and grabbed a fat three-fingered pinch for his cheek.

Just as the sun had sunk completely and darkness was starting to settle in, he looked at me with a new sense of urgency in his eyes.

“Nick,” he said, “I gotta make it out of here. I’m thinking of moving to Robins, down by Cedar Rapids. I mean there just ain’t shit here. I’m almost thirty. ”

I asked him what he’d do there.

“They got plenty of welding jobs down there,” he said. “I just need to find someone to introduce me.”

“That’d be great,” I said forcing a smile. “I’m sure you can find something, I think it’s a great idea.”

“I mean this ain’t much of a life,” he said, sweeping his hand toward the broken house and spitting a long stream of brown juice on the dirt.

“You’re lucky to get out of here, you know that,” he said.

I looked at him. “Sometimes I think I am, but other times all I want is the peace and quiet. “ I said. “Big cities are so busy, man. It’s no place to raise a kid or settle down.”

“Shit you remember when we were kids?” He said. “Playing catch, riding bikes, little league. All that.” He smiled.

When we were about eight, we’d buried a time capsule deep in my yard. Inside were some baseball cards, Nerds candy, and a sheet of paper. On it, we wrote “Jake and Nick, Best Friends Forever.” We dated it and both signed it in red ink. For many years after, we’d quiz each other about the date we buried it. Jake was always better at remembering than me. By our senior year in high school, we’d both forgotten.

“Hell yeah,” I said, sipping beer, “I don’t think a kid could do better than we did.”

Darkness had now almost completely engulfed the fields below his house, and we could just barely see the outline of oaks in the distance.

“I know you’ll find something in Cedar Rapids,” I said, turning the conversation again in hopes of convincing myself as much as him. “I wish you the best, man. I really do.”

He smiled. “I know you do, man. Thanks….”it sounded like he wanted to add more, but instead he let loose another strand of tobacco juice.

“I better get going,” I said. “Don’t wanna keep you too late, know you probably have to work early tomorrow.”

“Great seeing you bud,” he said, shaking my hand goodbye. “Next time you’re back give me a holler. Who knows, maybe I’ll be in Cedar Rapids.”

“I know you will be.” I said. “Take care, man.”

Backing my car out of the driveway, I stole one last look at the house and at Jake, still on the stoop, starting on a new beer and staring at the ground in front of him. I was resigned to the truth that when I came back, these hills, and Jake, would still be here.

Introducing:

Nick Compton

China Timeline? Have been in China on-and-off since 2007, in Beijing steady since 2011. Have been a student, journalist, and communications professional here.

Three words to describe your time in China so far? Promise, doubt, demolition

Most memorable moment from my first year in China? Realizing that there was a huge and fantastically foreign world outside of Iowa

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life? Volunteering for the news service at the Beijing Olympics

My writing history? More inconsistent than I'd like, but something close to my heart.

Favorite word to use in writing? said (h/t to the previous Loreli writer)

One word to describe the process of writing? Courageous

Posted Dec 9, 2015

Last week's party was fun. Thanks for indulging us.

In particular was this item of interest, the Drunken Poetry box:

"I went to the worst kind of bar hoping to get killed.

instead I just got drunk again." - words on the poetry box. name that poet.

This box swallowed mounds of literary detritus that night, some of which I'll share below. This is one of the only times you'll be seeing commentary on this site about people's creations. Enjoy.

There was the predictable gibberish of an unpracticed poet on a few beers (bless the effort):

Why is it always me?

The one they seem not to see

Leaving only the slightest trace

Of a man without grace

A man without a place

Just trying to find

Somewhere kind

Somewhere outside my mind

Somewhere with a penguin

Perhaps with Ursula Le Guinn

But not the mighty Qinn

‘Cos you’ve not seen nothing like him

It’s gonna be a bumpy ride

‘Coz, son, you ain’t got nowhere to hide

except over there in the closet.

**

Ba rumpa rum rum, drunk drum tongue.

Badum dumb dumb, badum um drunk

Drum tongue; tower, ban, stunned –

Bell tower rings for whom + flowers of evil

Bauderie blooms, fungus on the tombstone

Shrooms above bones + blood in the womb –

I mean blook boils in the room.

Bride and groom loom looney as

Cartoons, Beijing car zoom zoom

Ba rumpa rumm, drunk drum tongue

Banging punk rock fun, blunders and no plan

Like Alice in Wonderland.

**

Scary place, the mind of a cat

Fuck that shit, I gotta scat

Nevermind, nevermind, you twat

And what can anyone say to that?

**

He’s too hot to need a fan

So chill, cool off, at least pretend

To like him for who he is, a simple man

That only needs a friend.

**

On a wintry Friday night in Beijing I wandered my way among a bunch of drunken poets.

They handed me some paper, I hoped I wouldn’t blow it

Shit

I blew it.

**

Tomatoe, tomahto

Go fuck yo-self.

Despite this majority flotsam and jetsam, there were indeed real signs of literary prowess at the bottom of those bottles:

A bee goes from flower

Red to flower yellow.

Son takes cookies mom said no about.

Your CEO rounds pennies

None are ever the wiser

The details are never shared

And they die with you

Greed is small in any amount.

**

Lolita’s relief

Children read poems in fields

And put on lipstick.

**

My company is a zoo

All my co-coworkers are animals

There’s a parrot that repeats

And the giraffe in high heels.

All the pigs wear suits

My company is a zoo

Everyone has a pen

Everyone slithers to lunch

Everyone fingerpaints with poop or powerpoints

Everyone is trapped

**

Do not go gentle into

that goodnight,

Old age should burn and

Rave at close of day;

Rage

RAGE

Against the dying

Of the light.

And how can we miss out on the brown-nosers:

There once was a literary gang

Whose launch went off with a bang!

We all got drunk and high

With the ladies of Loreli

“Look, read and listen,” we sang!”

And the cautious mockers:

AMY PLAYS A LOVE SONG

KERRYN RELINQUISHES HER DIGNITY

HANNAH APPLIES LIPSTICK

THE LADIES OF LORELI

PROCREATE LIKE BONOBO

And of course, the heartsick:

The pulses throbbing

Thoughts pounding

So many Jing-A beers pounded

And you, heart throb, on the brain.

**

For too long,

Far too long,

My heart held on,

To something not worth,

My time spent.

It’s time to discover,

What Beijing life has to offer.

To new beginnings! <3

Yep, everyone's favorite, the RAUNCH:

Part 1

Sex is good

Sex is fine

Doggy style

And 69

Part 2

69 is so high school

you try to preserve your virginity

but you think you’re cool

and try to have anal

Part 3

Gotta keep your man satisfied

Gotta keep hymen intact

At sex, you might not be qualified

Other than at having a vagina compact

Part 4

You like to read

But you also like to give head

It’s okay, one day you’ll be dead.

But what came up as unique, which I guess shouldn't be surprising, is people's love-hate tension toward the party, the people, and the Jing:

I can’t read all these characters,

On the signs and streets and the dance floor,

In this city where no one stays.

We’re like beer cans washed up on distant shores,

And there’s snow down in the Sanlitun if you

Know where to look late at night,

And the girls down in the Gulo [sic] dance on

The old things the boys drink and fight.

One liver, and ten more Beijing bars.

One liver.

In this city you can’t see

The stars.

**

Ah, mulled wine – what a drink!

How I love your happy orange slice!

So many hipsters, o so little time

How many hipsters does it take to line

A hutong? Don’t answer that –

More than the milled wine’s spic

**

Beijing’s out to kill.

It’ll lure you into the hutong

To sniff your blood,

And to suck

The ticks of your lifestyle

Out of the flesh they seek.

We think we will be purified.

Instead, we puke,

Listen to Compact Dicks,

And find joy in the defiled.

I get it -- why else do we write if not to unravel the tangle of our heartstrings? And why else be a writer in China if not to ache over our braided feelings toward this country? Just be sure to have a drink and a friend on hand -- no one should be tackling that heartache without serious assistance.

"IsraelPlan" posted Dec 3, 2015.

"IsraelPlan" (以色列计划) is a public WeChat account that introduces Israeli and Mideast cultures and issues to a Chinese audience. Kelly Yang is among the contributors and curators of this platform, which has 30,000 followers.

Introducing:

Kelly Yang

Kelly Yang (杨燕) can easily be considered a mover and shaker across Beijing's various circles. She co-founded Vericant, an education consulting company that helps North American schools interview and evaluate their Chinese applicants. Vericant is known among Beijing foreigners as a coveted employer, and is internationally recognized for its commitment to honesty. After building up the company, she recently left to run an Ed-Tech incubator in Beijing – helping other educational entrepreneurs grow their startups, and in the meantime is training to be a life coach. She is an active church member of Solomon's Porch, and a frisbee player in her free time.

She also helps running a WeChat account that is of poignant importance today, "IsraelPlan" (以色列计划). She writes posts in Chinese on Mideast issues. It goes without saying that this discourse is regrettably under-explored in this country.

Kelly also writes about her personal travel experience and shares with her friends. She has a public WeChat account called "The Beautiful Life" (美好生活), where she shares her suggestions and insights based on her travelling experiences. So far, she has written about her travel experiences in Pakistan, Kenya, Israel, Qinghai, Wuyuan (Jiangxi Province), Japan, Bali, Hong Kong, Paris, Chicago, Shanxi, Xitang (Zhejiang province).

Let's cut to the chase -- in China, what is missing in common discourse about the mideast and specifically Israel?

The impression of Chinese people on Israel as a country and Jewish people as a nation is very limited. When talking about Israel, all Chinese people know two things: small country and always at war. When talking about Jewish people, two other things come to our mind: they are smart and good at doing business. However, there is a lot more to Israel and Jewish people that Chinese don’t know about. Like Israel’s beautiful scenery and advanced technology, the innovation and openness, the deep culture and long history. Israel is a real melting pot. It is also a startup nation. One will only know how safe Israel is after being there. Our WeChat blog wants to help those who can’t personally be there experience a real taste of Israel.

If you could say something to all Chinese people about Israel (/the Mideast), what would you say?

Israel is a safe and modern country.

Scan to follow IsraelPlan on WeChat.

Before my first trip to Israel, I thought all of the people there will be praying all the time and people would lock themselves in the house to avoid danger. But I was so wrong. Tel Aviv is like New York, and Jerusalem has a lot in common with Beijing. People there are super modern and open. Not everybody is religious. There are bars open 24 hours. I think sometimes we rely too much on TV to get information, and we also use too much imagination. You just need to get out there to see the real world.

What's your relationship with Israel?

My husband is from Israel. Before I met him, I was already very familiar with the country because there is a lot of information about it on Bible. I’ve been wanting to go and see the place where Jesus lived.

I actually didn’t start the WeChat account. It was started a few years ago by a Jewish person and I joined earlier this year to help run it. I think the mainstream media has misled its audience on this country. We want to bring more objective information to Chinese audiences.

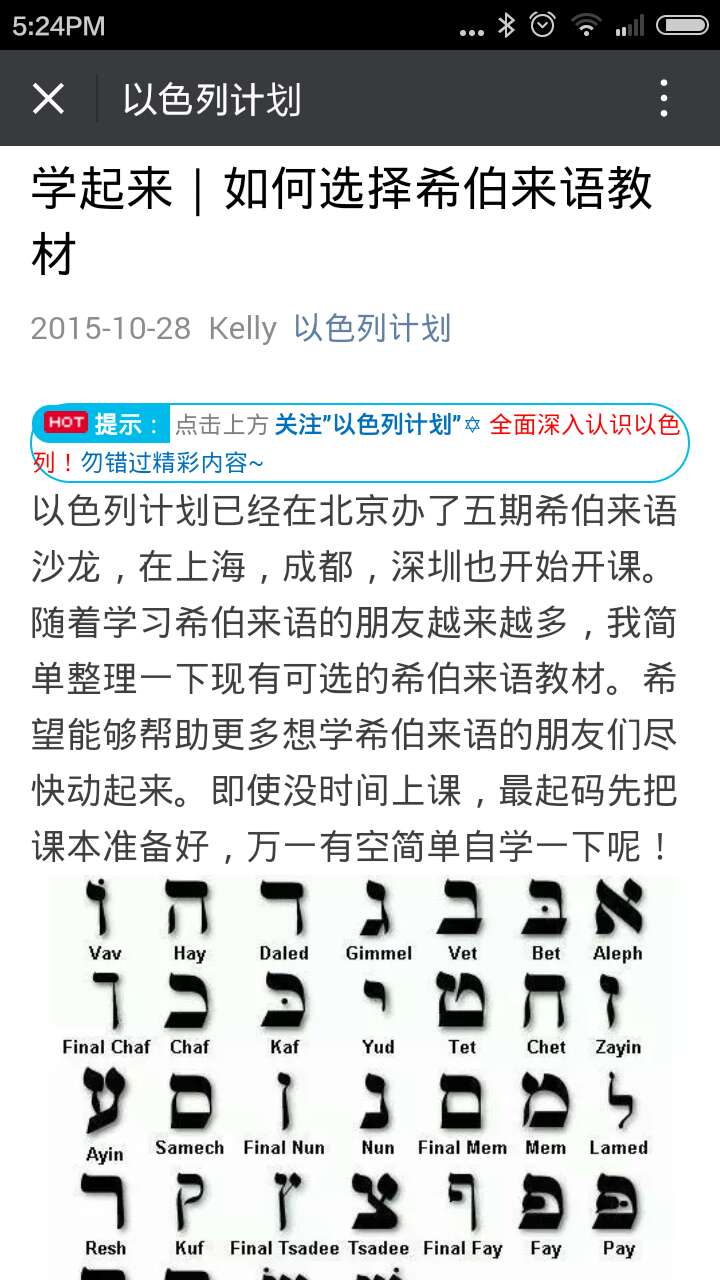

What would you say have been your pinnacle articles?

I wrote an article about learning the Hebrew alphabet, and I think that reflects my attitude the most. In the article I wrote about the “mysterious Hebrew alphabet” and how much more you will learn behind all the letters once you really start learning. There are a lot of similarities between Hebrew and Chinese in this way. To me, Hebrew and Chinese are representatives of their two countries. Both are very deep and mysterious, both had changed a lot over a long history, and yet they have so much in common. The article has got around 6000 views last time I checked.

How has reception of the blog been?

The WeChat account is ran by 6 volunteers and we have 30K followers and readers now. In addition to the articles we are posting, we are also planning to organize some more bilateral events. Like taking our Chinese readers on a tour to Israel and bringing Israeli youth to experience China.

And for your personal WeChat account, why do you write about your travel experiences?

I am a very curious girl. I like doing new things and going to new places. I also learn by seeing and doing. Whenever I go to a new place, I learn so much about local people, culture and food. It works much better than reading on books or watching TV. I decided to write my experiences into wechat posts and share them with my friends not to show off, but to encourage my friends to do what they want to do. I heard so many people telling me they want to go to this and that place, but they don’t have time. I want to show them you can actually go to those places even if you have a busy job.

READ ARCHIVE

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.

January Curator:

Charlotte Smith

Charlotte is a nomad multipotentialite whose various projects, creative pursuits and side hustles can be explored at https://clisviolet.journoportfolio.com/. She deeply values connection and the exchanging of ideas. Her greatest accomplishment has been finding people who are a continuous source of inspiration. (Photo credit: Phillip Baumgart)