Premiering new and upcoming writers in China.

THE KING'S CROCODILE TEARS

This week we're showcasing longer piece than usual, an alluring tale by Beijing's Deva Eveland. So let's start with the author interview!

What inspired this piece? It’s inspired by Cambodian folklore. When I lived in Phnom Penh I was fascinated by these stories. They’re for sale everywhere as illustrated books, dirt cheap, probably for children or something. I didn’t understand them, but that made them all the more intriguing. For example, an image of two boys watching an elephant burn on a bonfire, and smoke rises up in which a green skinned being holding a golden scepter appears. What is going on? Are they cooking an elephant? Is it a funeral pyre? Is the green skinned creature the soul of the elephant?

Finally I persuaded my Khmer language tutor to try to teach me to read. The Cambodian script isn’t easy, but we went through some of these stories at a painstakingly slow pace. I frequently had reading comprehension problems that were as much cultural as grammatical. Cambodia has a very ancient civilization. A lot of concepts don’t translate and there’s no handy English language reference to look them up.

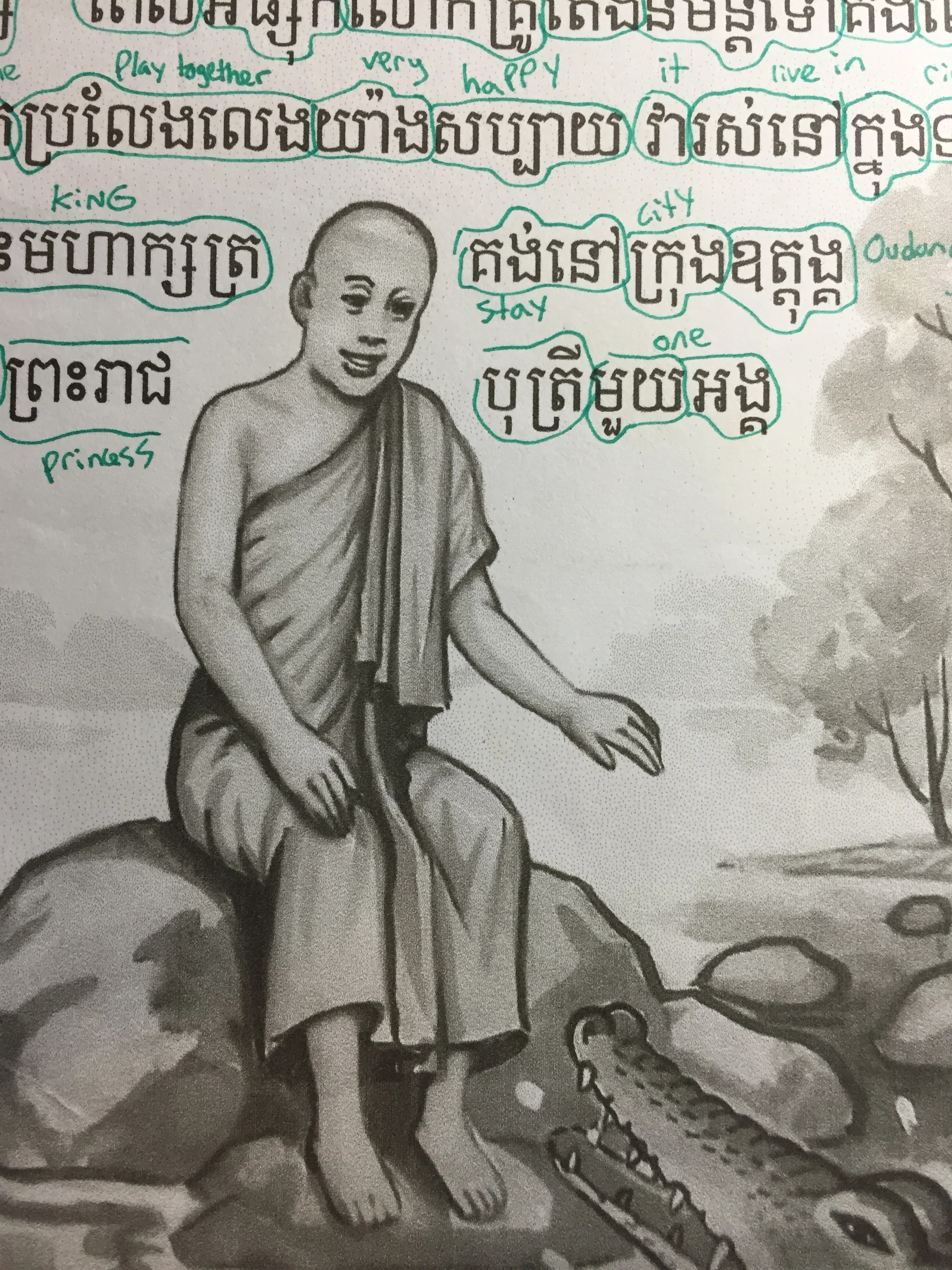

What do you want people to know about it? The King’s Crocodile Tears borrows liberally from a story about a crocodile who swallows a monk he’s trying to protect and accidentally suffocates him. The croc goes on a killing rampage until the king’s men hunt him down. I was fascinated by Ah Tone. He seemed to be the most dynamic character in the story in spite of being a monster. In the original story the king is heroic. Cambodians tend to be loyal to the monarchy, so making him a petty despot, having him unable to repel an invasion, having him influenced by a Rasputin-like sorcerer were all my additions. I also felt making him a despot might be more apt as Cambodia has been misruled probably for centuries at this point (though the king isn’t meant to represent any leader in particular).

How long did it take you to write it, what was the process like, etc? Originally I tried to write it entirely from the perspective of the crocodile but that proved difficult. The writing went quickly once I put myself into the head of the king. Since then I’ve gone back multiple times to try to prune it down to a reasonable size. I know it’s still long for a short story…you probably deserve a medal if you’ve plowed through it and you’re still reading this.

Three words to capture your feelings toward China? 听不懂

Moment you realized writing was an important part of your life? If I don’t have a creative outlet my mental health deteriorates, so this moment of realization continues to assert itself from time to time. I’ll go about my life steadily growing ever more angry/depressed/paranoid/misanthropic for no apparent reason. Then I realize it’s because I’ve forgotten to take time out to write.

Your writing history/notable writing projects: I’m revising a novel, though this is notable to me only. I’ve published a few short stories published here and there. One at Pavilion Literary Magazine, another on New Dead Families.

Favorite word to use in writing: Friendlily. Actually I’ve never used this word in a story, but I do love adverbs. They’re forbidden fruit. Every fiction writing guide cautions against them, so whenever I feel justified slipping one in, I take a dark pleasure in it. Friendlily does appear right at the beginning of Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and I’m jealous, even if the result is clumsy as hell.

THE KING'S CROCODILE TEARS

by Deva Eveland

“My King, the invaders have overrun the Province of Lea Houv.”

“And what is so important there?” I demand, kicking aside the slave who plucks stray threads from the embroidery of my slippers.

Lord Veasna touches his forehead to the floor. “Prasat Pech, Liege. The empire’s ancient seat.”

How wearisome. There is nothing there but ruined palaces and jungle. Some delight in picking through the debris left by our ancestors. Not I. It is difficult enough to rule this land without enduring the judgment of all those dreadful stone eyes. Let the barbarians claim the mildewed statues if they wish.

“What else?” I ask.

Another minister creeps forward. I cannot recall his name. “O Sovereign, flooding in the South threatens to decimate the rice harvest.”

I snort. The ministers fret over the arrival of more boat people. They fret over a judge beaten to death by a mob. I listen wearily to these conundrums, nodding assent to whatever their consensus seems to be. If they cannot agree, the solution that requires the least effort.

As my mind wanders, I turn to the jasmine stuffed couch where Princess sips tea. Nothing pleases me more than to watch her dance; no other embodies Sita as she. With a wave of the hand I dispatch the gloomy courtiers that I may watch her practice. A bard plays while the stage is set. He annoys me, groaning away as he plucks at a two-stringed lute. The songs are ancient ones, and he wails them as dirges for those bygone days. Sensing my boredom, servants begin to coo.

“Truly, Majesty, your eyebrows arch like Rama’s bow.”

“He is correct Sovereign. For generations our empire has not been blessed with such a handsome monarch. Your regal countenance must be chiseled from the same stone as the colossal heads of Prasat Pech.”

Before I can cuff the buffoon, a symbol’s crash begins the recital. But as I watch Princess, knee raised, fingers bent back at the knuckle in the k’bach of a leaf, she begins to seize. Her headdress topples off and lands as a golden stupa in the center of the room. When the Ravana dancer grabs her by the shoulders, the whole court freezes up like a herd of frightened deer. The only sound is the shuffling fabric of her costume as she jerks around. The Ravana changes his grip, but cannot steady her, and her face swings into his mask, spinning the tower of blue heads clockwise. Now three sets of monstrous eyes are glaring right at me as though to menace the throne itself. The masked idiot gropes around, but only manages to clutch the hem of Princess’ costume, and she flops to the ground in a burst of skittering glass beads. The fool is left holding only one corner of her sarong. There is my precious girl, her twitching bare legs fully exposed to the court. The ladies-in-waiting look down at their feet. Perhaps she is dying, but none of them stir.

“Help her!” I bellow.

But they just cower. I run up and scoop her from the ground. Looking into her porcelain eyes, I see no iris, no pupil. She chews on her tongue as a dog tears at meat. Then she falls limp. Black blood foams from her panting lips. I hold her hair back as she hacks up a final wad of scum, then lay her on the reed mat where musicians play. Doctor Rattanat creeps forward to chant over her unconscious body, his assistant fumbling with the incense. I look over the court—what good are any of them? So many frightened deer. Two guards present the Ravana for punishment. His quavering legs cannot hold him upright, so they must lift him by each arm. The stack of heads on his mask is still leering at princess as though to plot some further violation. I run the idiot through with a sword. An arrow would be truer to the Ramayana, but I haven’t the energy. Anyway my temples pound with a searing pain, so I retire to my chambers, proclaiming, as I depart, that the ladies-in-waiting are to be executed the following afternoon. The agony clouds my thinking; I announce that I shall costume myself as Rama and slay them with a bow.

The next morning I know Princess will come imploring me to spare their lives. I await her in the Garden of Longevity, sipping a bowl of rice wine. Four peons bear her upon a litter in the form of Hamsa, the king of lovely birds. Inside the gilt frame she reclines on lime and turquoise cushions. Her brow is damp with sweat, though the sun is still low in the sky.

“I would beg you, My King.”

“Do not beg.”

“You mustn’t execute them. They did nothing.”

“But flower, that is precisely why I must do it. Execution is a king’s privilege, and so I must exercise it, lest they forget who I am. I would that you grasped the order of things.”

“And I would that you as adept at slaying the invaders as you are at slaughtering my handmaidens,” she mutters.

“They conspire behind your back. They dilute your medicines.”

Princess begins to weep. Why does she wound me so? Rather than prolong an argument her frail constitution cannot bear, I unveil the special gift I have prepared for her. It is like an intricately constructed dollhouse, only for mice. There are balconies and a portico carved with bas reliefs of makaras. Behind the façade a hidden system of ladders allows the rodents to scamper from window to window. I have ordered them dyed different colors that she may tell them apart. Though she is peaked, princess smiles at the diversion. After a time she can no longer focus, and I give her leave to return to her chambers.

#

That afternoon I act as though I had never ordered the execution. The ladies-in-waiting are cowed, as they should be, but the ministers are not. They hover about like flies, handing me contradictory estimates of the invaders’ cavalry. Am I now a stable boy, counting horse tails and elephant trunks? For what do I pay my generals?

My dying flower. Her once honeyed voice rumbles with black phlegm. She must have coughed up buckets of the stuff by now. Her hand, though trembling, is still feminine as she draws a silken square to her face. Then my delicate blossom is wracked with spasms. Black tendrils droop from her nose to the handkerchief. Through the violent clacking of her bangles, her tears of shame, the courtiers try to conceal their alarm, but their careful nonchalance gives them away. The ladies-in-waiting hover, always smiling as they fold her soiled dainties away with tricks of palmistry. They rinse her fingertips with rosewater, adjust her tiara. Too cheerfully. They echo the physicians: “The quantity of phlegm is not so great as before. You are recovering, my lady.” Privately, they gossip about her funeral arrangements.

“Leave, all of you. Bring Doctor Rattanat.”

What can anyone do? Rattanat maintains that she is affected by evil winds, but he cannot drive them from her. His assistants coat her spine with bitter smelling medicine, and when they scrape it off with a bronze coin they press so hard they leave bruises like slender eggplant up and down her back. A week later, when the bruises disappear, they apply the hot cups. The thought of red rings branding her soft teak skin—only just healed—anguishes me. I pace up and down the patio as the physicians light their candles, on the point of seizing Chief Doctor Rattanat by his long beard. Yes, I could easily order those whiskers braided into a thorny bush where fire ants nest, but princess stays me with a tender glance. When Rattanat finishes her back looks like a treatise on lunar cycles. This helps nothing.

#

“My King, the port of Kompong Klah has fallen to the invaders. What should be done?”

What should be done? What should be done? Princess should be cured, that is what should be done. I refuse to lift a finger until the cure is found.

“Please, Your Highness. Their general demands—”

“You should concern yourself with my demands, not those of foreign devils. A foul wind torments Princess and attracts malevolent spirits. Now go and solve this problem. Only after will I attend to these other trifles.”

My ministers are not loyal. It is only the hope of winning Princess’ hand that keeps them from hatching a palace coup. Once I delighted in feeding their ambitions, privately letting each think he might be the one. Now, I would rather marry her to a river monster than one of these foul sycophants. All of them so eager to slip a ring on her dying finger. Not for love, no, only so that they might don the crown. My crown. I am the one who loves her. Still, let them think they are her suitors.

The ministers resume pestering me. First, they beg to levy more peasants into the war effort. Once I grant permission, they are emboldened to beleaguer me with every annoyance they can cook up.

“More boat people arrive daily, Liege.”

“Have we not border guards, Lord Veasna?”

“Illustrious Sire, they have been mobilized against the invaders. The boat people’s numbers swell and they have erected a most exotic temple. It is said the walls are washed as white as boiled rice—there are neither murals nor statues, as though their gods are in hiding. It must be torn down My King, for they are planning to install a great warlock inside it. They say he is capable of causing stones to grow in his enemies’ stomachs. He need only ball his fists to do so. Then by cracking his knuckles, he may dispel the tumors of those who pay his ransom.”

I start. “Dispel them? Cure them?”

“He is skilled in all manner of witchcraft, My Liege.”

“Leave their temple unharmed. Bring this sorcerer to me.”

“Your word is law, Sovereign.”

#

When the warlock enters the throne room, the court physicians are already lined up, sulking behind kindly smiles. Though the foreigner is vibrantly turbaned, the rest of his ensemble appears to be cut from the sort of tarp one finds on the floor of a fishing boat. A wisp of gray hair the length of a buffalo horn sprouts from a mole on his cheek. He smells like a cooking fire. I press my palms together and raise them so that the tips of my middle fingers are level with my eyes. It is an absurdly respectful salutation; his deranged mien would merit chest level at best. The warlock does not acknowledge or return my sampeah. Instead he creeps directly to the jasmine stuffed couch where princess lies whimpering. Doctor Rattanat coughs, entreating me to call for the warlock’s head. Ordinarily I would. Today, the physician’s discomfort amuses me more. Princess complies with the examination like a sleepy child. The ladies-in-waiting flop her to a seated position so the warlock can wind a piece of straw around her finger. As he flicks the loose end of grass, he grunts. Perhaps he is muttering incantations or perhaps suffering from abdominal gas. Next he pries open her lips with his grubby fingers as though she were a horse. Doctor Rattanat stifles another cough.

“You sound ill,” I suggest, “perhaps he should examine you next.”

“I am well My King, but your concern for my health is humbling. I do not deserve it.”

When I turn around the warlock has taken off her tiara, unpinned her coiffure, and holds her long black hair extended in his hands. He is sniffing it. The guards petition me with their eyes, but even if I were not desperate for the cure, to acknowledge the trespass so far into the examination would bring greater shame. The warlock approaches my throne neither kowtowing nor erect, but stooped. He speaks in the high, lilting accent typical of a foreigner:

“Her bones, Highness. They shall jelly before the season of rain. And her eye sockets are loose; she must scrunch closed the lids when sneezing else she loses the balls. This will only work for a while. In time they will fester like peeled lychees left on a sill. This shall attract flies. Immense ones, of a size never seen before in your kingdom. And her nails, Highness. Brittle. Brittle and also loose. Whether they snap apart like cockroaches underfoot or slip from her fingers like dead leaves, they shall not last until the mangoes ripen.”

I try to demand the cure, but my throat is so weak that only a whimper escapes.

“That is not all, Highness. Her tongue is graying. The blood, you see, which makes it pink, is draining into another part of her body. Where, it is too early to say. But when she loses the sensation of taste, check her stool for blood. Yes, bloody stool would be the best. If not, the sanguination will clot somewhere else, perhaps as ballooning in the head, or clumps that dangle from her elbows—”

I cannot bear it. I am a cavern home only to swarms of dirty, fluttering bats. From this darkness, I watch the warlock’s fingers dance in the air, drawing out the shapes of who knows what—entrails unraveling or ash being scattered into the wind. I strain to pull the image of her pure beauty up from the depths of my mind. Her perfumed hair being combed by slaves. A smile of curiosity blossoming on her lips. Her delicate hand as she dances, the thumb and middle finger pressed together as a bud, the index finger arched back as a shoot. Only this reverie keeps me from tumbling off my throne. When I recover, the court is in chaos. The ladies-in-waiting are sobbing. The physicians are engaged in a heated debate over the benefits of sliding a live snakehead fish down her throat to suck the evil wind from her belly.

“Would it work?” I ask the foreigner. He sniggers.

“Certainly, the fish could survive down there for months if she ate nothing but guppies and tadpoles. The occasional water insect, Highness.”

“But would it cure her?”

“No chance at all! None of us can cure her—”

The guards’ spears snap to attention.

“—but—” He grins at the spearmen with a twinkle in his eye.

“—if there is such a doctor, I will locate him, for I have the knowledge of far seeing.”

#

From the treasury I select a shallow basin of wrought silver ringed with sapphires. This piques the ministers, for the sorcerer will be allowed to keep it after the ceremony. Let them grouse. What have they done to earn their own baubles and silks? They only present me with problems. A solution would be well worth a few jewels. I have many, after all. Not so many as my great, great grandfather, but enough. The dish has a beautiful wheel of reincarnation etched in its bottom, but the design is soon submerged under a pool of blood. First, the warlock drains the throat of a peacock over it using the sharp edge of a sugar palm frond. Then he slices the leaf across my own hand. While slaves wipe my palm, whimpering and apologizing, the warlock stirs his concoction with a straw whisk.

They are closing the shutters one by one. Only golden threads of the afternoon sun sift through cracks in the joinery. It is better in this gloom, for I will not be able to see him cut Princess. There is a smell that reminds me of the countryside. At first I presume it is only the body odor of the warlock, but then I realize he is burning bunches of dried grass. No sooner are my eyes adjusting to the darkness than the smoke obscures everything again. The warlock seizes my wrist. I know it is he, for he rasps in my ear, “The moon, Highness.” He is presenting me with the round dish of blood. It could be like a pale moon, yes, as though appearing on a dark night from the mist, which is the smoke from the smoldering grass. And then I feel a terrible stinging as the warlock pinches the wound to squeeze out more blood. I try to focus on the moon, but it goes wobbly as dribbling liquid ripples the surface. In my dizziness I am swimming. Shapes congeal.

A cluster of river rocks extends from the shore beside a pagoda. Atop this rock pile sits a monk. I move towards him, swishing my tail vigorously against the current. With perfect serenity he raises two hands up to his mouth. “Ah Tone, Ah Tone,” he calls. What does this mean? It is not from any prayer I know, but I sense he is using the right words. He reaches out with gentleness to stroke my snout. His fingers tickle my nostrils. I bite his arm, softly, playfully. He laughs from his belly. The sight of such a wise teacher giggling like a child fills me with warmth. “Ah Tone,” he laughs again, and I realize it is my name. I nuzzle in his orange robes, and though my jaws are closed, a sharp tooth jutting out of my lip catches on the cloth. I feel him un-snag me with fatherly affection. Then we are splashing in the water, wrestling. He wraps his arms around my fat neck and his legs around my belly. With his stomach to my back we dive down to the bottom of the river. It is murky again. Yellow flits of light stab the clouds of swirling mud. Or no, they come from gaps in the wooden shutters of a room. The smell of brine fades, is choked out by the burning sweet grass.

I find myself flat on the floor, fingers splayed, elbows crooked, hips writhing against the dark wood. I am a human again. The ministers cower around a lamp in the corner of the room. I gnash my teeth at them and roar like a crocodile.

“Muster every soldier! Leave only a skeleton force to repel the invaders and dispatch the rest up and down the waterways inquiring at each pagoda. The monk who summons the river beast Ah Tone to play with him must be brought to the capital. Search high and low till you find him, it is a most sacred duty to the throne.”

Looking into their dumb eyes, I doubt their enthusiasm and add, “I will behead every minister under this roof unless the monk stands before me in a week’s time. So say I, your king.”

#

By the time the monk arrives at court, Princess has lapsed into a coma. There is no time for formalities; the healer is rushed straight to her side. While I watch his shaved brown head bobbing over the saffron folds of his robe, Doctor Rattanat sidles up to my throne with an air of urgency.

“Highness! With this new development, a cure will be far beyond the reach of a simple monk.”

I pretend that I cannot hear him over the chanting and take a sip of rice wine. Resuming in a stage whisper, he tries a different approach.

“I would be careful of this one, My Liege. The soldiers who apprehended him tell a most peculiar story.”

“Yes, go on.”

“Well, as they pulled anchor he preferred to hang back at the rear of the barge, gazing behind with a sort of expression. ‘Forlorn’ they said. At first this seemed natural, as he was so reluctant to leave the pagoda. There were throngs of monks weeping at his departure, you see.”

“Ridiculous—have our monasteries degenerated into schoolyards? Have they no self-discipline?”

“Quite right, My King. Well, he kept looking back, long after the pagoda was out of sight. So a few of the soldiers, they began to follow his eyes. He was looking at something in the water—a great crocodile. It followed the barge, Highness, maintaining a distance, but always there. It was an ill portent. Yes, quite ill, so the captain ordered them to shoot at it with their crossbows. They could not kill it, but they drove it away.”

“And how did the monk react?”

“He is a gentle man Highness. Quiet and peculiar. Fitting for a cloistered life, if nothing else.” The physician flutters his hand at the monk’s back as though to shoo him off to the pagoda. Leaning in closer, he adds, “There are still other cures My King.”

As he tells me this, he motions to his assistants. They are hauling in a sloshing urn, presumably with snakehead fish inside it. I imagine the fat, slime-coated creatures being stuffed down Princess’ throat, I feel a headache coming and signal the steward for another bowl of rice wine. No sooner do I begin to slake my thirst though, than Princess is already sitting up, rubbing her eyes. The monk has dispersed the foul wind with a simple prayer. It is gone!

“What reward may I offer you, teacher? You need only ask it, for I am king, and all that is within this realm is mine to parcel out as I please.”

The monk lowers his eyes.

“For the monastery of course! A new library perhaps, or a great golden Buddha…?”

“I only wish to return to the pagoda, Your Highness. There are many novices to train. I fear the burden is too great on my brother monks.”

Monks cannot dissemble well. He pines for that loathsome river monster, Ah Tone. There is nothing natural about a man, even a holy one—especially a holy one—bathing with a giant lizard. Besides, what if the evil winds return to torment my flower? No, the monk must remain at court. It occurs to me that if he married Princess, she would always be safe.

#

It is well that the monk shows little interest in the wonders of the capital, for as the war draws nearer, we are obliged to sail downriver for a period. To save face, I tell him it is a pleasure cruise arranged as a reward for his service to the throne. We make our way through the little used Moon Gate, where a cobblestone path winds down an overgrown embankment and onto the riverbank. There docks the most splendid of my royal barges. It appears as a great fat naga floating on the water, not only because of the seven snake figurehead blooming out of the prow, but also because of many thousands of tiny mirrors cut in the shape of scales and inlaid into the gilded hull. The cluster of cabins rising out of the deck are capped with layered roofs and a great golden spire that the world may know it is no mere boat, but a floating palace. My barge shines with a heavenly radiance under the sun, blinding those peasants who would dare to gaze upon it from the shoreline. I look at the monk to confirm his understanding of these things, but he is watching the coolies loading it with supplies.

“Have your parents selected a bride for you yet? You never told me.”

He looks startled.

“My Liege, I am devoted to the Awakened One.”

“It is commendable to take the cloth for a period in one’s youth and you have acted to bring honor to your parents, but one must lead a full life. Indeed, it would be tragic for a man of your talents to languish in the cloister. Surely, when you have coin, you will start a family?”

“I love women as my sisters, Highness.”

I interrupt him with a great belly laugh.

“Or perhaps your parents have saddled you with some ugly sow, and you are looking for a way out?”

“My parents were killed in the border clashes of three years past, Highness.”

For a time we watch the coolies passing bundles and urns from their tiny rafts to the royal barge.

“Well then,” I say. “You have saved the royal bloodline and I mean to offer you Princess’ hand as guerdon.”

His face turns the color of steamed crayfish. “Most Potent Sire, I am without words…”

“Yes My King would suffice.”

Without meeting my eyes, he only fiddles with the creases of his orange robe.

“There are several days until we arrive at the site of our glorious new capital. Think on it and give your answer then,” I say, pressing my palms together and raising them to the level of my nose. He folds his hands above his bowed forehead, and shakes them in submission. I leave pleased.

We set sail the next dawn. Watching scaled rooftops and varicolored flags fade into mist, I am seized with the dread that I shall never again set foot in the halls of my palace. Was this what my ancestors felt as they fled Prasat Pech? They lived in palaces of stone, and I of wood. Will my descendents live in palm thatched huts? I turn my gaze to a cluster of stilted hovels perched above the shallows. I wait for their crooked poles to disappear from view, but we do not seem to be moving at all. It is as though the current were an illusion, my barge wallowing as aimlessly as a buffalo in a mud pit. I shut myself in my private cabin and snuff out the lamp. The pain behind my eye is greater than ever. It is so strong I batter my head against the walls to try to knock myself out. The lamp smashes on the deck and I roll around in the glass. Slaves prattle at the door, but I have barricaded myself inside. Could the monk, who has after all cured Princess, also relieve my headaches? I will broach the subject when we arrive at the wartime capital.

#

The next morning, as I breakfast in the dining cabin, my mood improves. Through the wooden colonnades, I am soothed by glimpses of the sparkling current. Birds glide on the breeze, chasing insects and chittering their morning songs. I order one of the slaves to summon the monk. He will cure my headaches and he will agree to marry princess here and now, for I am king and that is how I wish it. But as I await his presence, there is a loud crack of splitting wood, and my breakfast catapults across the deck. Ropes snap, sailors call out, boots thump. Lord Veasna rushes in, tripping over himself to deliver the ill tidings.

“My King—the monk—a great crocodile has attacked the royal barge. It’s unbelievable…it tore up the planks with the fury of a typhoon. The teacher, deep in meditation, would not heed the shouting of the deckhands. O Radiant Lord, he is feared dead.”

Feared? Unlikely. I know this ingrate gloats beneath his exaggerated grief.

“Please Sire, I know he was as a son to you. Let his funeral be the grandest ever witnessed in our lives. If I can assist in any way… Let the procession hearken back to the halcyon days of Prasat Pech! Whatever you ask of me, I am at your disposal.”

“Very well, fetch me the sorcerer of the boat people.”

Lord Veasna stutters like a schoolboy. He would rather I were so overwhelmed with grief that I would place my confidence in him to oversee the cremation. Step by step he would weasel his way into my graces, eventually marrying Princess and stealing my crown. I can see it all in his eyes. But I do not for one moment believe the monk is dead.

“I tire of repeating myself. You asked my will, and I replied that I would counsel with the sorcerer. Now go and bring him to me.” As I speak, I jam my knife into the neck of a prawn on the floor, pulling up the impaled head as a prize. I hope Lord Veasna understands that I could do the same to him.

#

I meet the sorcerer aboard another barge, one with the prow of a garuda clutching snakes in its taloned fists. It is not so magnificent as the naga, which had to be scuttled after the crocodile attack. At least most of the treasure was salvaged. From the coils of cloisonné beads and stacks of sparkling diadems I pull out a small silver dish, one I won’t much miss, to act as the scrying basin. The warlock examines the filigree with displeasure.

“It will suffice Highness, if you do not wish to go so deeply into the crocodile’s mind.”

I sigh, and flutter my hand at the open chest. The warlock picks through it, and then another, before selecting one of my most treasured heirlooms. The brazier is shaped like a lotus flower with petals of electrum converging around a diamond-studded seed cup. I will miss it. Princess moans as her blood dribbles over the dish’s embossing.

“Does it sting, Flower?”

“I only mourn the loss of my inheritance, Father.”

At least her cruelty is queenly.

The leaf slices across my hand and I spurt out of the cut, blistering hot like the seed of Shiva. I fear I will dissolve into a million particles, for how can a small spray of blood hold its form in the cosmic ocean? But the warlock’s chanting presses into me from all sides, forging a new corporeality. I am a tadpole of blood, bobbing along the glittering surface.

My snout glides firmly through the ripples, holding the center of the river. Normally, I would hug the shores, but today they are dangerous, for with the teacher on my back I cannot hope to hide below the surface. As we glide down the river, astonished fishermen greet us with cries of wonder.

“Behold, a monk standing upon the back of a crocodile! Still as a statue, his robes catch the wind like a great orange sail!”

Crabbers drop their traps, farmers abandon their oxen in the fields, and grandmothers let their sour soups burn as they stare dumbfounded. There is singing, crying, chanting, and laughter, but my only care is to bring the teacher safely home. I hasten to maneuver myself into the waters of the tributary where men seldom tread.

A breeze, dappling the water’s surface, soothes us. The teacher voices his relief in a chant that hums along the ridges of my back and lulls me into a gentle bliss. My tail swishes like a calligrapher’s brush. Breathing in the cool air, I taste rambutan and follow the odor to swaying bows along the bank. A band of macaques was here, grazing on the fuzzy red clusters and perhaps drinking from the river’s edge. Their dung is sour and fruity. Stippling this musk are the fragrances of wild grasses and blossoms. But there is another odor shelved in the air. It is an unfamiliar breed of humans; these ones are foreign. A catalogue of violent deeds wafts from their bodies—caked blood, burnt flesh, stale adrenaline. Though human, there is also something crocodilian about them. It is the brash odor of a young beast who first wanders out of his mother’s territory to challenge an older male for dominance.

How can I protect the venerable teacher? Spear points gleam from the riverbank. Without thinking I unhinge my jaws and arch my back that the teacher may climb into my mouth. I will protect him inside the vault of my own belly. The teacher knows what he must do, but his hand rests unsteadily on my jaw. He is too far beyond the vulgarities of our world to understand the savage tearing of flesh. But I know, and I will shield him from them. I grunt this urgency. The teacher gingerly probes the roof of my mouth with his leg. First one foot tickles my tongue, then another, and he slips down my throat. I have felt many creatures wriggling inside my belly: Turtles, carp, serpents, shrews, macaques, and once even a young calf, but this being I must protect with my life. If I cleave to the center, gliding just below the surface, the clumsy horde will not notice our passing. I’ll vomit teacher onto the soft grasses that grow along the bank beside the pagoda. The golden spire will gleam, sweet incense wafting from its porches. As I picture the young monks running out to cheer his arrival, the image blackens. Is the grass beside the pagoda on fire? No, I am not there yet. But there is clearly smoke. Perhaps it is from the invaders, burning everything in their path. Thick smoke, I cannot breathe. I cannot identify myself. I cannot feel the monk’s heartbeat. I cannot see. I cannot breathe.

“Majesty! You are alive!”

Only the warlock looks unsurprised that I have journeyed back into my own being. My eyes are too bleary to concentrate very much on the courtiers crowded around, but I suppose they are struggling to feign sympathy. “Wine,” I groan, but fall into a deep sleep before taking even a single sip.

#

I have not separated my mind from Ah Tone’s as cleanly as before. My royal barge smells too strong, and sometimes I feel the monk’s heartbeat as though it were issuing from my own stomach. It is imperative that the crocodile be captured soon, for the monk will suffocate in the dumb beast’s gut long before they reach the pagoda. Unfortunately, Lord Veasna’s efforts disappoint me at every turn.

“O Potent Sire, we have captured twelve more crocodiles.”

“So, what was in their bellies?”

“Fish, Sire.”

“And upriver? That is where you must look.”

“Each hunting party we send upriver is intercepted by the invaders, King.”

Now Princess flings open the cabin doors and strides up to my throne, a parade of ladies-in-waiting mirroring her urgency like a trail of ducklings. This barge lacks the privacy to which a king is entitled. I glance out the window at my new palace, still only a stack of lumber piled in a jungle clearing.

“Father, the coin you expend on this crocodile hunt could be put to better use. Troubles abound, and our house is not so grand as in the days of Prasat Pech.”

“But flower, that is precisely why I do it: For the stability of our house. Your groom lives still in that beast’s belly.”

“Such a groom is unlikely to produce heirs, Father.”

Princess raises an eyebrow, but I cannot interpret her meaning.

“Father, I have secured an army of mercenaries from the Kingdom of the East.”

“Ha! King Dara IV is little more than a fat rice merchant wearing a king’s crown. How much, I pray, does that greedy tyrant demand?”

Princess and I watch in silence as grunting porters take each urn and chest, leaving my cabin as bare as a beggar’s cup. When there is but one lacquered case left, I strike the hand of the lout who moves to take it, and he shuffles away.

“Not this one,” I tell Princess. “The treasure it holds is as old as our line.”

#

“O Great King, it is as you feared. The crocodile climbed onto the bank and ejected the great teacher from its mouth before the assembled monks. Inspecting the corpse, they were astonished to discover no tooth marks at all—he suffocated in the belly. O, it is a ghastly affair Majesty!”

Tears dribble down my cheeks. After a moment I realize that I weep in error, for I am not the crocodile, I am the king. A king does not pity. Even so, I cry for several days without interruption. It is a great annoyance. My wine turns salty after only a few sips. Royal documents are destroyed before I can affix my seal. Concubines must crouch at my bedside to mop up the excess liquid as I sleep, or else my pillow grows too soggy. Even then, my dreams are still overrun with visions of the crocodile’s despair. One night I am awakened by the screaming of a concubine: I have snapped my powerful jaws onto her pinky. She must have been too careless as she dabbed the tears from my cheeks. Her revolting, puckered face, a caricature of agony, makes me want to let go. Yet the taste of blood holds the river beast Ah Tone inside me. I roar and thrash until I have ripped the digit free, then slip back under the covers to imagine that it is Princess’ finger in my mouth.

The next morning, I do not need Lord Veasna’s breathless report to know what has happened.

“…Highness, I cannot bear to tell you…yet another crocodile attack. O Worthy Liege, it is Princess! She was bathing under the shade of jacarandas along the bank, when the demon lizard shot out of the water and swallowed her whole!”

Yes, a single gulp. I already know, and the knowledge comforts me, for she is still alive. The monk did not die at once; I felt his heartbeat weakening over several days, but the stupid beast didn’t understand why. Ah Tone’s revenge will fail.

“Fetch the sorcerer,” I command.

“Though I am loathe to add to your troubles Majesty, there are those—not I—who claim that this foreign seer has undue influence over you, which he exercises to the detriment of the very outcomes you would seek. Very incorrectly, traitors assert that the gods no longer favor your rule. Perhaps the best way to nip such nonsense in the bud would be to distance yourself—”

“I said bring him to me you ninny! Are you deaf and blind? Unless he stands before me within the day I shall slice off your ears, scoop out your eyes, and deliver them to fishermen along the docks, saying ‘The owner makes no use of these, but perhaps you can use this offal as bait!’”

Lord Veasna scurries off stooped in a continuous bow.

#

I run my bandaged hand over the lacquer case holding the final treasure from the era of my great-great grandfather. I open the lid and lift out the brass bowl, admiring its intricacies for the last time. It mimics a woven basket for gathering rice, symbolizing the plentiful harvests of a burgeoning empire. But the playful workmanship also suggests the undulations of nagas, the celestial custodians of the river, the empire’s lifeblood. The warlock snatches it up and turns it over, unable to find gems he could pry off to sell.

“Do you see the detail with which the scales are wrought?” I ask. “No living artisan could match it. Each is engraved with a blessing upon my house. It shall bring you good fortune.”

The warlock holds the dish to his nose with a look of impatience more than admiration.

“Of course, it is in the old script, such as we can no longer read.”

He plops it back on the deck with a shrug. Shame overwhelms me as I struggle to remember how my grandfathers would have explained the brazier’s import. When the warlock rips the edge of the palm leaf across my cut hand, the searing of the wound comes as a relief. The brazier is powerful; my essence melts right into the crocodile’s.

Men scream out their death throes in several tongues. A burning village on the shore sprays volleys of cinder into the afternoon breeze. We are hiding in the cool mud, content despite the mayhem around us. The part of us that is Ah Tone is content with the fullness of our belly. The king is content too, because he feels Princess pulsing inside. For a moment the sovereign fights to swim out into the open water to be captured, but the crocodile would rather not. Even as we hear humans crashing through the bamboo along the bank it is difficult to act. Now Ah Tone would rather jet into the open water, and the king would rather not. So we do nothing. Spearmen swarm around, yelling in sharp voices like honking geese. The sovereign recognizes them as the mercenaries he has paid for, and grows impatient for us to be captured, but the crocodile is too frightened to surrender to them. The soldiers balk, confused that we do not respond. The king is confused too, until the crocodile explains that a predator finds the courage to kill in the struggle of his prey. It seems for a moment that the soldiers might just leave again, but then the first spear flashes hot in our back. It provokes another and another. They stick our snout, causing us to twist up. The king, overcome with pain, commands them to stop.

“Stay your spears, for I am ruler of these lands. Princess lives inside me—you’ll kill her too! You have been paid to save our house, not snuff it out you rodents.”

But it is the crocodile Ah Tone who voices this protest, bellowing a guttural roar that eggs the soldiers on. A shrieking brute leaps forward and impales us with such force that his spear snaps apart. The broken shaft tears through the crocodile and the king. It slides through Princess as though she were a hunk of meat roasting on a spit inside the lizard’s hot belly. We are the blood of three beings, seeping out of a thrashing animal husk. As we diffuse into the lapping waters, our only form is the pull of the river’s current.