China's Rural Waste:

Waiting for a Tipping Point in Consciousness

Written by Roma Eisenstark (scroll to bottom for interview)

An expansion of her original article in Slate.

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

In the vast, garbage-strewn landscapes of China's countryside, waste has modernized while disposal practices have not.

When I first rode through rural Hebei province, I was immediately impressed with the scenery. It was not flashy, like Guilin, or some such mountainous region covered by mist. Instead, it was wide, flat, and empty. There were a few skinny trees along the side of the road, but for most part the ground was covered by one plant, corn, that stretched over the horizon like a green blanket. Interspersed between the swathes of green, a labyrinth of waterways fanned out like human veins. Every mile or so, the water would take over the earth, and corn fields would give way to wide, shallow marshes with reeds and mud islands springing up from below. Insects buzzed all around. The leaves of willows hung lazily over the water.

I'd come from the United States to teach English in Moucun (pseudonym), a small village about three hours outside of Beijing. Because I am greedy (or crazy), I decided that I'd live in the village for half the week and live in Beijing for the other half. I wanted to live in both a small town and a modern city, so that I could experience both sides of China.

Every week when I got off the Greyhound-like tour bus and onto a smaller one that would take me to the village, something else about the landscape would grab my attention-- it was covered with garbage. Along the side of the road were scattered heaps of plastic cups, candy wrappers, napkins, and an endless multitude of plastic bags, their translucent folds glistening in every possible size, shape, and color. From the bus I'd see more rivers and lakes, their long, steep banks having become de facto dump sites-- static waterfalls of discarded objects, waiting for a slight nudge to snowball down into the water below.

I took a closer look one day when walking down the road. There were the typical items of plastic food packaging, but there were more surprising objects as well: old sandals, hair brushes, broken children's toys, sweaters-- all coated in gray dirt. Their formerly bright colors were now completely subdued, as if they were trying to blend in with the fallen leaves around them.

One day, when leaving school, I saw one of the school's maintenance workers burning something on the ground outside the front gate.

"What are you burning?" I asked. He smiled at the foreigner. "Trash!" he said. I asked him why he had to burn trash. "Don't people collect it?" I asked. He told me yes, but he still had to burn it. I wasn't sure why. Communication in the village was always difficult. My Chinese isn't as good as it could be, and people tended to have thick accents. But the conversation got me thinking: did they really have trash collection? If so, why did they have to burn their trash? And why were there big piles of garbage?

Next to the school's front gate, a few workers spend their days in a little building with a bed and a TV in it. Together, they rotate security shifts. One afternoon I went over and asked one of them if he knew where our school's garbage went. It took a long time for him to understand. "Oh!" he finally said, amused. "Why do you want to know?" "Because I'm interested in garbage." I said. He laughed. He told me to talk to Teacher Wu (alias). "He takes out the trash," he said.

Luckily, I knew who Teacher Wu was. That evening, I found him and asked if he took out the garbage. He laughed. "Why are you interested?" I told him I was thinking of writing an article about it, and that garbage interested me. He laughed again.

"Do people come on a regular basis to collect your trash at home?" I asked. "What about in the nearby city?" "No, no one ever comes to collect the trash," he said, his tone one of frustration. "We have to take it ourselves."

"They come to our house," a woman who worked at the school joined in. "But not as much as they come to the city. In town they might come everyday, but here they come every three days. Something like that."

Teacher Wu nodded in agreement, although her statement contradicted what he had just said about no one ever collecting the trash. It didn't seem like there could be much ambiguity about when someone picks up your garbage.

I asked Teacher Wu where he took the trash for our school. Was it to a processing center? He laughed again. "There are no processing centers out here! It's just a pile. A big pile of garbage!" Although still laughing, his tone was tinged with frustration. I asked if I could go with him and see it. He smiled, incredulous. "You want to go see it!?" I nodded, earnestly. "Alright, fine. If you want, next time I take the trash out there, you can come." I thanked him profusely. I was truly excited to see the big pile of garbage. But I had to wait. Chinese New Year vacation began the next day, and I would go back to Beijing for a month. I'd have to wait all that time to see the trash.

Before I left for vacation, I talked to one of the science teachers who had grown up in the village. She said she had learned to swim at a nearby famous lake in the area. She told me that there had once been a huge fish population in the lake, and people would fish there often. Now the fish were nearly all gone. She said that even if you did catch any, you wouldn't want to eat fish from the lake. I asked if people still swam in the lake and ate the fish. "Yes," she said. "People don't pay attention to those types of things. They don't care." She told me that residents litter all the time. "They just throw their trash on the ground," she said. "There's trash all over the village."

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

According to an April 7th article on the People's Daily site entitled, "Waste Surrounding Villages, The Urgent Need to Bring the Countryside's Garbage Administration Under Control," the situation in Moucun exists in rural areas all over China. Trash just builds up around residents' homes, or they are forced to throw it in natural gullies or water ways. Sometimes they burn it or bury it. Statistics from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development show that in 2013, the country had 588,000 administrative villages, and of those, only 37% had any kind of waste disposal system. Fourteen provinces had waste disposal in less than 30% of their villages, and in a few provinces, not even 10% of villages had any means of disposing of waste. Wang Ning, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Vice-Minister, said that his country has 650 million permanent residents living in rural areas, and together they produce 110 million tons of garbage every year. Of that, 70 million tons cannot be properly disposed of.

People's Daily claims that the central government is playing close attention to the situation. It quotes Premier Li Keqiang as saying this year, "As for trash and sewage, we must hold environmental governance in the highest importance. We must make the countryside into a beautiful, suitable place to live." These kinds of articles, emphasizing the scope of the problem and the determination of the central government to fix it, can frequently be found on the People's Daily and Xinhua sites. If People's Daily and Xinhua publications are "the mouthpieces of the Party," than its intention toward rural waste is clear-- we recognize the problem, and we will solve it.

In the United States, a Gradual Evolution in Mindset

Sometimes when I speak with people in China about pollution, they ask me if we have the same problems in the U.S. I often tell them that, though the U.S. now has better capacity to dispose of its waste, it wasn't always that way.

"You know, when I was a kid, we might have thrown a candy wrapper out of the car window without thinking," my mother told me recently. She grew up on in Pennsylvania in the late 1950s and 60s. She remembers an important moment of change being when First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, wife of President L.B.J., told everyone to, "Plant a tree, a shrub, or a bush," in her typical Southern drawl accent. Lady Bird Johnson was also famous for the phrase, "Where flowers bloom, so does hope." She believed that national beautification was intrinsically intertwined with other issues such as poverty, crime, and mental health. If the land was beautiful, it would raise the spirit of the people.

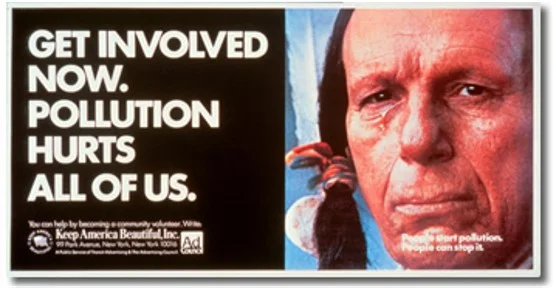

My father remembers a tipping point as being the famous "Crying Indian" public service announcement of 1971, in which a Native American, "Iron Eyes Cody," sheds a single tear when he witnesses pollution. My father said that the ad was on television several times a night. He also remembers huge billboards encouraging people not to litter. At the time, my father was living in a small town in Kansas. His garbage was collected about once a month. In order to cut down on waste, the family would burn their trash regularly in an oil drum in the backyard. "The trash was better to burn back then though," he said. "There was much less plastic." Once a month, collectors would come take the ashes away. He recalls that by 1965, the collectors came more often and they stopped burning trash.

More public awareness developed in 1987 when the Mobro 4000, a barge carrying 3,168 tons of garbage from New York, was denied permission to land at its intended destination in North Carolina. The barge then traveled from place to place, as far south as Belize and all the way back to New York, each time being refused permission to dispose of its cargo. The case may have been an isolated incident, but the wide media coverage it drew alerted the public's attention to the issue of solid waste management. It may have been one factor that led to the dramatic increase in recycling rates that occurred in the late 1980s and 1990s.

I remember getting our first recycling bin from Los Angeles county, where I grew up, in the early 1990s. It was a big yellow tub. Now, recyclable items outnumber other waste-- the recycling bin is always more full than the trash.

Practices in Beijing

After learning that the village probably had little by way of waste disposal facilities, I didn't feel comfortable throwing out my garbage there anymore. Only living there three days a week though, I didn't produce very much. I figured it wouldn't be too much trouble to pack my trash back to Beijing each week. But that got me wondering: how did Beijing dispose of its waste? Was it any better?

Everyday, an army of small vehicles--9,797 of them, according to the 2014 China Statistical Yearbook-- penetrate the city. They take what they collect to transfer stations, where it is compacted and shipped in specially-built containers to disposal facilities. These disposal facilities consisted of seventeen landfill sites, four incinerators, and three composting plants in 2013. The main waste disposal technology in Beijing is landfills, with 56% of the city's waste disposed of that way in 2013.

Recycling exists independently, in the for-profit sector. Migrant workers from the countryside sift through trash cans or make house calls to collect bottles and cardboard from residents. Oftentimes you see them riding through the streets with giant bales of empty plastic bottles, sheets of cardboard, or broken electronics strewn together on the backs of tricycles, several feet up in the air. They ride to the outskirts of the city, where they sell their wares to recycling depots. Plastics are then resold to mom and pop operations further from Beijing, where individuals mostly in small-scale, family businesses then clean, melt down, and process the materials. In his book, Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade, journalist Adam Minter describes the plastics recycling industry that was formerly centered in Wen'an County, Hebei Province. Before the county banned plastics recycling because of environmental concerns, it was where almost all of Beijing's plastics ended up. None of the recyclers had safety equipment or took any measures for environmental protection. According to Minter, although Wen'an's industry no longer operates, these small-scale, environmentally unsafe plastics recycling businesses still exist all over northern China.

It's clear that Beijing's waste management system is overburdened. Beijing's landfills are running over capacity, and many will have to close ahead of schedule. For the future, Beijing is looking to develop more incineration plants with technology in place to limit air pollution and potentially create energy. Many incineration plants, however, have met opposition from locals who fear that air pollution will not be adequately controlled.

One potential way to limit the amount of waste that needs to be incinerated or buried would be to increase recycling and composting efforts. This, however, would require greater knowledge and participation on the part of city residents, in addition to increased city infrastructure. Because the majority of residents are not educated on how to sort garbage-- landfill waste, recycling, and compost-able kitchen scraps usually get tossed out in one single bin. Unless independent trash-pickers remove recyclables, a bin's entire contents typically get picked up by one truck and taken to a transfer station. Most transfer stations don't have the capacity to sort through the waste they receive. As a result, a great deal of recyclables and kitchen waste ends up in landfills.

Outside Big Cities, Rural Communities Struggle to Keep Up

Beijing still has a long way to go. And yet, along with Shanghai, it represents one of the most sophisticated operations in the country. There's been a high level of investment both from the government and from the environmental technologies industry. A great deal of attention has been paid on how to make it better.

But what about the countryside? As incomes rise throughout the country, it is not only residents of big cities like Beijing who can afford to buy more stuff. Rural residents now have much greater purchasing power, and many of the new products they buy come covered in elaborate, "modern" packaging. While access to new products has improved in rural areas, the means to dispose of the waste they create has not. Most local governments don't have the resources to install waste disposal facilities like landfills, environmentally sound incinerators, or composting plants. Even if they are able to, many local governments lack the knowledge and manpower necessary to staff such operations. The problem of "heavy construction, light management," is typical. In such scenarios, local governments are able to acquire short term funds to build waste management infrastructure, but lack the resources to keep the projects running.

Only a few decades ago people in rural areas produced little waste, and much of that was biodegradable. Something like a glass bottle was highly coveted, and always recycled. Now, it seems, China has adopted Western trash, but not yet the infrastructure to deal with it.

Most of the people I spoke to in Moucun expressed frustration about the lack of waste disposal in their village. They were certainly aware that it was a problem, but they felt that there was nothing they could do to change it. The pervasive attitude was one of reluctant acceptance. Even if people don't like seeing trash everywhere, they aren't fully aware of the potential health and environmental risks that trash can cause. Despite their frustrations, rural communities lack the money and knowledge necessary to combat the problem.

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

Spring in Moucun

After Chinese New Year, I went back to Teacher Wu. "When are you taking out the garbage next?" I asked. He laughed. "You don't want to come with me. Don't worry about it." "Really, I do want to come with you," I told him. "I go late at night. How could you go with me? Never mind it," he said. He was blowing me off. I asked him why he wouldn't take me. He shrugged and didn't answer. I tried to keep pressing, but he ignored me, talking to his friend and refusing to make eye contact. I didn't know what else to say.

I went back to the security guards at the front gate. I asked if they knew where the school's garbage went. "Oh yes," one of them who was particularly friendly, told me. "You go right down that road, then turn left, then keep going..." he drew an imaginary map on the table with his finger. I tried my best to memorize the route, but I knew it was no use. Seeing my confusion he offered, "After lunch, if you come here, I'll take you." I thanked him and told him that would be great. I asked him, just to make sure, if they processed any trash there. "No, no, in the countryside there is no processing. It just gets dumped next to the river," he said.

I never made it back to see the security guard after lunch. Before that, I was intercepted. My supervisor, Teacher Wang (alias) stopped me and told me to stop asking people about garbage. He said that though everyone knew it was a serious problem, it was also very sensitive. Environmental issues were sensitive to the Communist Party, as were foreigners. I could potentially get myself and the school in trouble. He reminded me that it was my job to teach, not to write articles.

My instructions were clear: stop asking about the trash. I knew he was in part warning me for my own benefit. And I was, after all, a visitor in the community. It wasn't my place to judge, or to get involved in such things. My writing an article about the village's trash wouldn't solve the problem. But it also seemed to me that no one could solve it if they weren't able to talk about it. I decided to push on, but to be discreet.

One day, I walked out the front gate and instead of turning right like I normally do to get to the main road, I turned left. I walked down the road toward an area of the village I'd never been to before. Almost instantly I was met by whispers by everyone I passed. "Foreigner, there's a foreigner," they said. I could tell that Teacher Wang was right, the presence of a foreigner was sensitive indeed. I had a sense that I wasn't supposed to be there, and a paranoid fear that all these people were spying on me. After I left, they would immediately alert the administration of where I'd been and that I'd probably been looking for a garbage pile.

It was a beautiful day, one of the first that felt like spring. The air pollution was down, and the sky was bright blue. I passed a bunch of people standing in a clearing. They were gathered around a big cement mixer, shoveling in gravel and water. Foreigner... foreigner... foreigner... I heard the whispers as I passed. I turned a corner, and entered what felt like a little neighborhood. Houses sat around an open space. I started to walk through it cautiously to the other side. A dog, who was lying lazily in the sun, stood up and growled. I tip-toed back to where I had come from. I worried the dogs might be trained to protect their property. They seemed to be saying what I assumed everyone else was thinking: "You don't belong here. Get out."

Finally, I saw a lady walking the other way through the open space. I decided that if the dog went crazy, she'd protect me. She was older, and looked stern. Her face was covered in lines. She gave me a quick look and continued walking past. "Hello," I said. She looked a little surprised and said hello back. I asked her if I should be afraid of the dogs. "Don't worry about them," she said. "If you don't bother them, they won't bother you." She asked me where I was from, and what I was doing there. "It's such a nice day," I said. "Yes," she said. "Walk around. Go anywhere. Don't worry about the dogs." I felt welcomed after that. I walked on confidently, passing the dog who had growled at me. He had lost interest and was fast asleep.

Eventually, I reached a river. Speckles of white light glistened above the emerald green water, which careened off in both directions as far as I could see. I looked down at the bank below me. Unsurprisingly, it was covered in trash. I couldn't remember exactly what directions the man at the gate had given me, but I knew the dump site must be somewhere close, probably along this river. And then it suddenly occurred to me: I was never going to find this long anticipated garbage dump. I didn't need to, because I'd already seen it. There was no massive pile of garbage where everyone went. It was just the same trash I'd been seeing everywhere. The whole river was the dump. Like many rivers were.

I had a strong sense of futility as I decided to end my research of the village's waste disposal. As an outsider, it wasn't my place to get involved. For things to change, the local government and residents themselves would all have to get on board. There would have to be massive infrastructure development. Investment would need to come from somewhere. A collective change in consciousness would need to happen.

I wondered what it would take to set those events in motion. For people to reject the status quo and take responsibility. What would it take for everyone to face the problem together? What will be the tipping point?

Introducing: Roma Eisenstark

Lived in Beijing in 2001-2002 as a high school exchange student, and then again in 2006. Roma returned to China as an adult in 2014, teaching and freelance writing. Originally from Los Angeles.

"When I got here in my late 20's, I realized China was something I actually cared about."

Most memorable moment from my first year in China: Walking out the door of my host family's house and locking it behind me without realizing I was still wearing my house slippers. Worried they would fly off, I biked to school barefoot and got lots of looks. My Yeye, (host Grandpa) later noticed my shoes still at the house and biked them to school. I knew he had a lot of concern for me.

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life: When I came back as a real adult. The other times had been in high school and college, and I went because someone handed me the opportunity. When I got here in my late 20's, I realized it was something I actually cared about.

My writing history: I think my best work I wrote in the first grade and was entitled Can't Walk Melissa. It was about a disabled child whose best friend was murdered by her teacher through the use of a "killing machine." Now I'm less interested in child abuse and spend more time thinking about values and the intrinsic assumptions we all make.

Favorite word to use in writing: Turgid.

One word to describe the process of writing: Connection.

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.