September 2015

Showcasing new writers in China. Posted Sept 29, 2015.

My Overeating Grandma

Original fiction excerpt by Carly Hallman (scroll down for interview)

Seven p.m. and the dusty streets buzzed with lights and life. A stream of workers trickled from the factory gates. Walking in groups of twos, threes, and fours. Laughing and smiling. Off to buy snacks or to enjoy an evening stroll after a grueling shift. The resemblance to the usual afternoon scene in front of my school's gates was uncanny—these workers weren't much older than me or my little sister, and looking at their young faces I understood that it was just circumstance that had created our differences: we were building our futures; they were building our country's export surplus.

We took a train here to Guangzhou to get Grandma a special wheelchair because she's so fat she can't fit into a regular one. Dad wants her, his mother, to be able to go outside and “experience life” in so far as life can be experienced on a sidewalk under a ceaseless cover of pollution. Mom, while understandably fearful for Grandma's safety if such freedom is attained, just wants the old woman out of the house occasionally so that she can have more time to pursue her own interests, which include drinking wine, shopping for dresses online, and gossiping with her cousin on the phone. As for me and my sister, we're just sort of along for the ride, my sister less so than me, and so that's how I found myself outside the factory with Dad while she and Mom stayed in the hotel room digesting their dinners and watching HBO on satellite.

“Hey,” Dad accosted a group of three tittering young workers as I played bodyguard in front of a Sichuan restaurant. I could've stood anywhere, but I liked the way the wafting spices tickled my nose.

Dad adjusted his glasses and held out a hundred yuan note. “I need a chair.”

One of these workers, a pock-faced girl with severe bangs, lunged for the money. “What kind of chair you lookin' for, mister?”

Dad dangled the note just out of her reach. “A fat one.”

The girl glanced at her friends, who nodded with what could've been either approval or indifference. “Yeah?” she said. “Maybe we can work something out.” She and Dad, seeking a little privacy to negotiate, stepped under a liquor store awning. I bit my lip. I had watched and would continue to watch similar scenes play out dozens of times on this week-long trip. Dad paid out bribe after bribe, but no one was able to deliver because this factory only made some, not all, of the parts; unbeknownst to us until later, the chairs were assembled and given their finishing touches in America.

***

Maybe I should've begun this tale of Grandma's wheelchair by saying this: Truth is very important to me; maybe the most important thing in my life. I'm only sixteen, so a lot of people think I don't know what I'm talking about when I talk about this, but I do. I know that truth is often misunderstood, misinterpreted. I know that truth differs from honesty; that honesty is the act of telling the truth. I know that without truth, there is no justice, there is no peace, there are no stories.

When I grow up, I want to be an investigative journalist. Mom always jokes that I was born in the wrong country and at the wrong time for a job like that. She thinks it's just a phase, that I will grow out of it and grow up to become something proper like a computer engineer or a corporate accountant or a housewife like her. Dad is on my side though; he says I couldn't have been born in a right-er country and at a right-er time, and even if he's wrong and Mom is right, it's not like I'm stuck here. There's a whole world out there to investigate; a million truths to be told.

***

But back to the fat chair: Unsurprisingly, we left Guangzhou empty-handed. Dad’s brother, my uncle, had been taking care of Grandma, but knowing we'd be back that night, he’d already rejoined his “nagging wife” and “snot-nosed son” (his words, not mine). Our otherwise-dark apartment flickered with the TV's glow, and we dropped our bags in the entryway, and Dad, not missing a step, marched, his head held high, to Grandma's room, where she lay propped up in bed by pillows, staring slack-jawed at a program set in imperial times.

“Mother!” he declared. “We shall go to America to get your chair!”

Grandma's gaze did not stray from the screen.

“To America!” He proclaimed again, adding, “And if we can’t get the chair in America, it's onward to Europe. And if we can’t get it in Europe, it's onward to Africa and—”

My sister, who'd since settled on the living room sofa with her cell phone, which is basically her best and only friend, chimed in, “But Dad, there aren’t fat people in Africa. Everyone there is starving. Why would they have fat chairs there?”

My sister is hardly a genius, but even I had to admit she had a point. However, her interjection did little to deter Dad.

“Well,” he reasoned. “Where else are there fat people?”

I rifled through my mind, memories, things I’d read until: jackpot. “Samoa!” I cried.

From behind his thick glasses, Dad’s eyes sparkled. “Yes, well then it's off to Samoa! And if they don’t have the chairs in Samoa, we shall—”

Mom rolled her eyes. “I think she gets the point, dear.”

But if Grandma got the point, she didn’t show it. It’s not that Grandma is a vegetable or anything like that. Her mind is very sharp, as is her tongue. She’s just a bit on the lazy side, and a bit critical of everything last thing we do, according to Mom, but Dad says it's just geriatric depression, which he attributes largely to her immobility.

Unmoved by Dad's declarations, Grandma continued watching TV and when she finally did say something, it was just about whose pimples she had to pop to get some damn food around here. Mom sighed and clomped into the kitchen. My sister tucked her phone in her pocket and followed after her to help—don’t think my sister is a perfect angel or anything; she only ever helps out in the kitchen because she loves using a knife because she’s a psychopath.

To the soundtrack of sizzling and of the chop, chop, chop of the knife’s blade against the cutting board, I watched Dad’s lean silhouette as it lingered in Grandma’s doorway. “America,” he said, as though planning, plotting, as though disbelieving.

***

In case you’re wondering, Grandma didn’t get this fat by accident or by chance or by genes; hers was a choice, deliberate. One night, we were sitting around the dinner table chowing down, as we were wont to do, when Grandma cleared her throat and made her big announcement. “I’m much too old for sex orgies,” she began. “And I’m not interested in travel or learning a new skill. So I'm going to devote myself to my deepest passion, to the one constant in my life, to the one thing that has provided me comfort and nourishment through all of my suffering, through all of my years...”

And so Grandma’s World Tour of Food began at a 24-hour dim sum establishment outside the park. She'd announced her intentions to anyone who would listen, including meat stick vendors, garbage pickers, street sweepers, police officers, and the old people who did tai qi in our apartment’s gardens. I'd helped with online publicity, writing about her endeavor on a blog I titled “My Overeating Grandma,” which quickly amassed tens of thousands of followers, and which caught the attention of dozens of curious reporters, many of whom showed up on the big day.

Grandma did not disappoint.

She plowed her way through three steamer baskets of soup-and-meat buns, four baskets of shrimp dumplings, six beef-stuffed rice flour pancakes, one bowl of spicy Sichuan noodles, two-and-a-half bowls of pork and chive porridge, one bowl of black sesame soup, sixteen vegetable balls, and three sweet egg tarts.

My Overeating Grandma took the country by storm. A documentary show was produced. Magazine covers were graced. Many newspaper journalists and many more bloggers covered all angles of her story. Was she an enviable wild woman, liberated and enjoying what precious time she had left on Earth? Or was she a bastion of corruption, of gluttony, of laziness, of what was wrong with the older generation and the younger generation too, and perhaps what was wrong with our entire nation?

In my own blog, I didn't bother with such speculation. I simply documented; I simply told the truth.

In those two short but glorious years, Grandma packed on seventy-some-odd pounds. She'd had a good run, but after visiting nearly all of the restaurants in Beijing—from Xinjiang to Sichuan, Mexican to Indian, Thai to Malaysian—she was understandably a bit bored with the whole thing, and too fat and tired to get out of bed. As suddenly as Grandma's World Tour of Food had begun, it was over.

Bedridden, her spirit waned, but her appetite didn't. She continued to demand massive quantities of food. My parents discussed hiring a personal chef, but Grandma wasn't too keen on the idea thanks to a distrust of strangers and outsiders she inexplicably developed—Mom claimed it was from watching too many films set during the Opium Wars.

As for me, I'd indeed enjoyed a small amount of internet fame with my blog, but the nation grew weary of My Overeating Grandma, no longer canvassing Beijing seeking the hottest new dish, but restricted to her bed, eyes fixed on the TV. As they say, everything passes, and as Grandma's fame declined, so did my blog’s and so did my own. But oh well and never mind, I suppose I still have studying for the college entrance exams to look forward to, right?

Introducing:

Carly Hallman

Her debut novel, Year of the Goose, is set to be released Dec 8, 2015.

"I grew up in a mobile home in a Texas town named after a Confederate General....before those [first] months in China, it seemed like traveling and being an expat and all of that was a right reserved for a privileged few—the rich, the glamorous, the Travel Channel hosts."

Hometown: This is always a tough question to answer. I was born in San Diego, California. I spent most of my school years in Granbury, Texas, a place I absolutely abhorred. I moved to Austin, Texas for university and my family moved to Shreveport, Louisiana. Earlier this year, my parents moved to Anchorage, Alaska. Let’s just say I’m from the U.S.

China timeline:

2006 - Nanjing; study abroad semester

2007-2008 - Yangshuo; volunteer work. Nanjing; language classes

2011-2013 - Beijing; instructor in an after-school program

2013-Present - Beijing; part-time tutor & full-time writer

Most memorable moment from my first year in China: I grew up in a mobile home in a Texas town named after a Confederate General. The first time I came to China (on a full scholarship) was the first time I’d ever left the United States. For me, the entire experience was revelatory: Not only was there a wider world out there, but I (yes, me! awkward, penniless me!) could actually play a part in it. Before those months in China, it seemed like traveling and being an expat and all of that was a right reserved for a privileged few—the rich, the glamorous, the Travel Channel hosts.

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life: Although there are innumerable downsides to living in China as an expat (pollution, traffic chaos, cultural/linguistic barriers, etc.), I returned here in 2011 with a positive attitude, as well as a concrete goal: to write and publish a book. Besides providing inexhaustible inspiration, China is an affordable refuge for those of us with literary/artistic aspirations and an aversion to the traditional workweek. Here, I can work a bare minimum of hours, but live in a pretty nice apartment, eat healthy food, and manage to make my student loan payments. Most importantly, I have time to write. So much time! I can’t imagine having a comparable lifestyle in the U.S. at the moment.

My writing history: Like nearly everyone who wants to be a writer, I’ve wanted to be a writer since childhood. I earned a B.A. in English Writing & Rhetoric from St. Edward’s University in Austin, TX in 2010. I sold my first novel to Unnamed Press, a cool Los Angeles-based publisher, less than a year ago. That novel, Year of the Goose, will come out in December 2015.

My latest project: I am currently working on a paranormal horror screenplay, four different novels, and a few short stories & essays. Did I mention how much time there is to write?

Favorite word to use in writing: Bashful

One word to describe the process of writing: Endless

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.

Posted Sept 20, 2015

China's Rural Waste:

Waiting for a Tipping Point in Consciousness

Written by Roma Eisenstark (scroll to bottom for interview)

An expansion of her original article in Slate.

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

In the vast, garbage-strewn landscapes of China's countryside, waste has modernized while disposal practices have not.

When I first rode through rural Hebei province, I was immediately impressed with the scenery. It was not flashy, like Guilin, or some such mountainous region covered by mist. Instead, it was wide, flat, and empty. There were a few skinny trees along the side of the road, but for most part the ground was covered by one plant, corn, that stretched over the horizon like a green blanket. Interspersed between the swathes of green, a labyrinth of waterways fanned out like human veins. Every mile or so, the water would take over the earth, and corn fields would give way to wide, shallow marshes with reeds and mud islands springing up from below. Insects buzzed all around. The leaves of willows hung lazily over the water.

I'd come from the United States to teach English in Moucun (pseudonym), a small village about three hours outside of Beijing. Because I am greedy (or crazy), I decided that I'd live in the village for half the week and live in Beijing for the other half. I wanted to live in both a small town and a modern city, so that I could experience both sides of China.

Every week when I got off the Greyhound-like tour bus and onto a smaller one that would take me to the village, something else about the landscape would grab my attention-- it was covered with garbage. Along the side of the road were scattered heaps of plastic cups, candy wrappers, napkins, and an endless multitude of plastic bags, their translucent folds glistening in every possible size, shape, and color. From the bus I'd see more rivers and lakes, their long, steep banks having become de facto dump sites-- static waterfalls of discarded objects, waiting for a slight nudge to snowball down into the water below.

I took a closer look one day when walking down the road. There were the typical items of plastic food packaging, but there were more surprising objects as well: old sandals, hair brushes, broken children's toys, sweaters-- all coated in gray dirt. Their formerly bright colors were now completely subdued, as if they were trying to blend in with the fallen leaves around them.

One day, when leaving school, I saw one of the school's maintenance workers burning something on the ground outside the front gate.

"What are you burning?" I asked. He smiled at the foreigner. "Trash!" he said. I asked him why he had to burn trash. "Don't people collect it?" I asked. He told me yes, but he still had to burn it. I wasn't sure why. Communication in the village was always difficult. My Chinese isn't as good as it could be, and people tended to have thick accents. But the conversation got me thinking: did they really have trash collection? If so, why did they have to burn their trash? And why were there big piles of garbage?

Next to the school's front gate, a few workers spend their days in a little building with a bed and a TV in it. Together, they rotate security shifts. One afternoon I went over and asked one of them if he knew where our school's garbage went. It took a long time for him to understand. "Oh!" he finally said, amused. "Why do you want to know?" "Because I'm interested in garbage." I said. He laughed. He told me to talk to Teacher Wu (alias). "He takes out the trash," he said.

Luckily, I knew who Teacher Wu was. That evening, I found him and asked if he took out the garbage. He laughed. "Why are you interested?" I told him I was thinking of writing an article about it, and that garbage interested me. He laughed again.

"Do people come on a regular basis to collect your trash at home?" I asked. "What about in the nearby city?" "No, no one ever comes to collect the trash," he said, his tone one of frustration. "We have to take it ourselves."

"They come to our house," a woman who worked at the school joined in. "But not as much as they come to the city. In town they might come everyday, but here they come every three days. Something like that."

Teacher Wu nodded in agreement, although her statement contradicted what he had just said about no one ever collecting the trash. It didn't seem like there could be much ambiguity about when someone picks up your garbage.

I asked Teacher Wu where he took the trash for our school. Was it to a processing center? He laughed again. "There are no processing centers out here! It's just a pile. A big pile of garbage!" Although still laughing, his tone was tinged with frustration. I asked if I could go with him and see it. He smiled, incredulous. "You want to go see it!?" I nodded, earnestly. "Alright, fine. If you want, next time I take the trash out there, you can come." I thanked him profusely. I was truly excited to see the big pile of garbage. But I had to wait. Chinese New Year vacation began the next day, and I would go back to Beijing for a month. I'd have to wait all that time to see the trash.

Before I left for vacation, I talked to one of the science teachers who had grown up in the village. She said she had learned to swim at a nearby famous lake in the area. She told me that there had once been a huge fish population in the lake, and people would fish there often. Now the fish were nearly all gone. She said that even if you did catch any, you wouldn't want to eat fish from the lake. I asked if people still swam in the lake and ate the fish. "Yes," she said. "People don't pay attention to those types of things. They don't care." She told me that residents litter all the time. "They just throw their trash on the ground," she said. "There's trash all over the village."

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

According to an April 7th article on the People's Daily site entitled, "Waste Surrounding Villages, The Urgent Need to Bring the Countryside's Garbage Administration Under Control," the situation in Moucun exists in rural areas all over China. Trash just builds up around residents' homes, or they are forced to throw it in natural gullies or water ways. Sometimes they burn it or bury it. Statistics from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development show that in 2013, the country had 588,000 administrative villages, and of those, only 37% had any kind of waste disposal system. Fourteen provinces had waste disposal in less than 30% of their villages, and in a few provinces, not even 10% of villages had any means of disposing of waste. Wang Ning, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Vice-Minister, said that his country has 650 million permanent residents living in rural areas, and together they produce 110 million tons of garbage every year. Of that, 70 million tons cannot be properly disposed of.

People's Daily claims that the central government is playing close attention to the situation. It quotes Premier Li Keqiang as saying this year, "As for trash and sewage, we must hold environmental governance in the highest importance. We must make the countryside into a beautiful, suitable place to live." These kinds of articles, emphasizing the scope of the problem and the determination of the central government to fix it, can frequently be found on the People's Daily and Xinhua sites. If People's Daily and Xinhua publications are "the mouthpieces of the Party," than its intention toward rural waste is clear-- we recognize the problem, and we will solve it.

In the United States, a Gradual Evolution in Mindset

Sometimes when I speak with people in China about pollution, they ask me if we have the same problems in the U.S. I often tell them that, though the U.S. now has better capacity to dispose of its waste, it wasn't always that way.

"You know, when I was a kid, we might have thrown a candy wrapper out of the car window without thinking," my mother told me recently. She grew up on in Pennsylvania in the late 1950s and 60s. She remembers an important moment of change being when First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, wife of President L.B.J., told everyone to, "Plant a tree, a shrub, or a bush," in her typical Southern drawl accent. Lady Bird Johnson was also famous for the phrase, "Where flowers bloom, so does hope." She believed that national beautification was intrinsically intertwined with other issues such as poverty, crime, and mental health. If the land was beautiful, it would raise the spirit of the people.

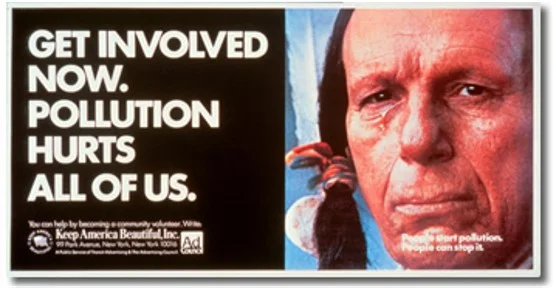

My father remembers a tipping point as being the famous "Crying Indian" public service announcement of 1971, in which a Native American, "Iron Eyes Cody," sheds a single tear when he witnesses pollution. My father said that the ad was on television several times a night. He also remembers huge billboards encouraging people not to litter. At the time, my father was living in a small town in Kansas. His garbage was collected about once a month. In order to cut down on waste, the family would burn their trash regularly in an oil drum in the backyard. "The trash was better to burn back then though," he said. "There was much less plastic." Once a month, collectors would come take the ashes away. He recalls that by 1965, the collectors came more often and they stopped burning trash.

More public awareness developed in 1987 when the Mobro 4000, a barge carrying 3,168 tons of garbage from New York, was denied permission to land at its intended destination in North Carolina. The barge then traveled from place to place, as far south as Belize and all the way back to New York, each time being refused permission to dispose of its cargo. The case may have been an isolated incident, but the wide media coverage it drew alerted the public's attention to the issue of solid waste management. It may have been one factor that led to the dramatic increase in recycling rates that occurred in the late 1980s and 1990s.

I remember getting our first recycling bin from Los Angeles county, where I grew up, in the early 1990s. It was a big yellow tub. Now, recyclable items outnumber other waste-- the recycling bin is always more full than the trash.

Practices in Beijing

After learning that the village probably had little by way of waste disposal facilities, I didn't feel comfortable throwing out my garbage there anymore. Only living there three days a week though, I didn't produce very much. I figured it wouldn't be too much trouble to pack my trash back to Beijing each week. But that got me wondering: how did Beijing dispose of its waste? Was it any better?

Everyday, an army of small vehicles--9,797 of them, according to the 2014 China Statistical Yearbook-- penetrate the city. They take what they collect to transfer stations, where it is compacted and shipped in specially-built containers to disposal facilities. These disposal facilities consisted of seventeen landfill sites, four incinerators, and three composting plants in 2013. The main waste disposal technology in Beijing is landfills, with 56% of the city's waste disposed of that way in 2013.

Recycling exists independently, in the for-profit sector. Migrant workers from the countryside sift through trash cans or make house calls to collect bottles and cardboard from residents. Oftentimes you see them riding through the streets with giant bales of empty plastic bottles, sheets of cardboard, or broken electronics strewn together on the backs of tricycles, several feet up in the air. They ride to the outskirts of the city, where they sell their wares to recycling depots. Plastics are then resold to mom and pop operations further from Beijing, where individuals mostly in small-scale, family businesses then clean, melt down, and process the materials. In his book, Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade, journalist Adam Minter describes the plastics recycling industry that was formerly centered in Wen'an County, Hebei Province. Before the county banned plastics recycling because of environmental concerns, it was where almost all of Beijing's plastics ended up. None of the recyclers had safety equipment or took any measures for environmental protection. According to Minter, although Wen'an's industry no longer operates, these small-scale, environmentally unsafe plastics recycling businesses still exist all over northern China.

It's clear that Beijing's waste management system is overburdened. Beijing's landfills are running over capacity, and many will have to close ahead of schedule. For the future, Beijing is looking to develop more incineration plants with technology in place to limit air pollution and potentially create energy. Many incineration plants, however, have met opposition from locals who fear that air pollution will not be adequately controlled.

One potential way to limit the amount of waste that needs to be incinerated or buried would be to increase recycling and composting efforts. This, however, would require greater knowledge and participation on the part of city residents, in addition to increased city infrastructure. Because the majority of residents are not educated on how to sort garbage-- landfill waste, recycling, and compost-able kitchen scraps usually get tossed out in one single bin. Unless independent trash-pickers remove recyclables, a bin's entire contents typically get picked up by one truck and taken to a transfer station. Most transfer stations don't have the capacity to sort through the waste they receive. As a result, a great deal of recyclables and kitchen waste ends up in landfills.

Outside Big Cities, Rural Communities Struggle to Keep Up

Beijing still has a long way to go. And yet, along with Shanghai, it represents one of the most sophisticated operations in the country. There's been a high level of investment both from the government and from the environmental technologies industry. A great deal of attention has been paid on how to make it better.

But what about the countryside? As incomes rise throughout the country, it is not only residents of big cities like Beijing who can afford to buy more stuff. Rural residents now have much greater purchasing power, and many of the new products they buy come covered in elaborate, "modern" packaging. While access to new products has improved in rural areas, the means to dispose of the waste they create has not. Most local governments don't have the resources to install waste disposal facilities like landfills, environmentally sound incinerators, or composting plants. Even if they are able to, many local governments lack the knowledge and manpower necessary to staff such operations. The problem of "heavy construction, light management," is typical. In such scenarios, local governments are able to acquire short term funds to build waste management infrastructure, but lack the resources to keep the projects running.

Only a few decades ago people in rural areas produced little waste, and much of that was biodegradable. Something like a glass bottle was highly coveted, and always recycled. Now, it seems, China has adopted Western trash, but not yet the infrastructure to deal with it.

Most of the people I spoke to in Moucun expressed frustration about the lack of waste disposal in their village. They were certainly aware that it was a problem, but they felt that there was nothing they could do to change it. The pervasive attitude was one of reluctant acceptance. Even if people don't like seeing trash everywhere, they aren't fully aware of the potential health and environmental risks that trash can cause. Despite their frustrations, rural communities lack the money and knowledge necessary to combat the problem.

Photo by Roma Eisenstark.

Spring in Moucun

After Chinese New Year, I went back to Teacher Wu. "When are you taking out the garbage next?" I asked. He laughed. "You don't want to come with me. Don't worry about it." "Really, I do want to come with you," I told him. "I go late at night. How could you go with me? Never mind it," he said. He was blowing me off. I asked him why he wouldn't take me. He shrugged and didn't answer. I tried to keep pressing, but he ignored me, talking to his friend and refusing to make eye contact. I didn't know what else to say.

I went back to the security guards at the front gate. I asked if they knew where the school's garbage went. "Oh yes," one of them who was particularly friendly, told me. "You go right down that road, then turn left, then keep going..." he drew an imaginary map on the table with his finger. I tried my best to memorize the route, but I knew it was no use. Seeing my confusion he offered, "After lunch, if you come here, I'll take you." I thanked him and told him that would be great. I asked him, just to make sure, if they processed any trash there. "No, no, in the countryside there is no processing. It just gets dumped next to the river," he said.

I never made it back to see the security guard after lunch. Before that, I was intercepted. My supervisor, Teacher Wang (alias) stopped me and told me to stop asking people about garbage. He said that though everyone knew it was a serious problem, it was also very sensitive. Environmental issues were sensitive to the Communist Party, as were foreigners. I could potentially get myself and the school in trouble. He reminded me that it was my job to teach, not to write articles.

My instructions were clear: stop asking about the trash. I knew he was in part warning me for my own benefit. And I was, after all, a visitor in the community. It wasn't my place to judge, or to get involved in such things. My writing an article about the village's trash wouldn't solve the problem. But it also seemed to me that no one could solve it if they weren't able to talk about it. I decided to push on, but to be discreet.

One day, I walked out the front gate and instead of turning right like I normally do to get to the main road, I turned left. I walked down the road toward an area of the village I'd never been to before. Almost instantly I was met by whispers by everyone I passed. "Foreigner, there's a foreigner," they said. I could tell that Teacher Wang was right, the presence of a foreigner was sensitive indeed. I had a sense that I wasn't supposed to be there, and a paranoid fear that all these people were spying on me. After I left, they would immediately alert the administration of where I'd been and that I'd probably been looking for a garbage pile.

It was a beautiful day, one of the first that felt like spring. The air pollution was down, and the sky was bright blue. I passed a bunch of people standing in a clearing. They were gathered around a big cement mixer, shoveling in gravel and water. Foreigner... foreigner... foreigner... I heard the whispers as I passed. I turned a corner, and entered what felt like a little neighborhood. Houses sat around an open space. I started to walk through it cautiously to the other side. A dog, who was lying lazily in the sun, stood up and growled. I tip-toed back to where I had come from. I worried the dogs might be trained to protect their property. They seemed to be saying what I assumed everyone else was thinking: "You don't belong here. Get out."

Finally, I saw a lady walking the other way through the open space. I decided that if the dog went crazy, she'd protect me. She was older, and looked stern. Her face was covered in lines. She gave me a quick look and continued walking past. "Hello," I said. She looked a little surprised and said hello back. I asked her if I should be afraid of the dogs. "Don't worry about them," she said. "If you don't bother them, they won't bother you." She asked me where I was from, and what I was doing there. "It's such a nice day," I said. "Yes," she said. "Walk around. Go anywhere. Don't worry about the dogs." I felt welcomed after that. I walked on confidently, passing the dog who had growled at me. He had lost interest and was fast asleep.

Eventually, I reached a river. Speckles of white light glistened above the emerald green water, which careened off in both directions as far as I could see. I looked down at the bank below me. Unsurprisingly, it was covered in trash. I couldn't remember exactly what directions the man at the gate had given me, but I knew the dump site must be somewhere close, probably along this river. And then it suddenly occurred to me: I was never going to find this long anticipated garbage dump. I didn't need to, because I'd already seen it. There was no massive pile of garbage where everyone went. It was just the same trash I'd been seeing everywhere. The whole river was the dump. Like many rivers were.

I had a strong sense of futility as I decided to end my research of the village's waste disposal. As an outsider, it wasn't my place to get involved. For things to change, the local government and residents themselves would all have to get on board. There would have to be massive infrastructure development. Investment would need to come from somewhere. A collective change in consciousness would need to happen.

I wondered what it would take to set those events in motion. For people to reject the status quo and take responsibility. What would it take for everyone to face the problem together? What will be the tipping point?

Introducing: Roma Eisenstark

Lived in Beijing in 2001-2002 as a high school exchange student, and then again in 2006. Roma returned to China as an adult in 2014, teaching and freelance writing. Originally from Los Angeles.

"When I got here in my late 20's, I realized China was something I actually cared about."

Most memorable moment from my first year in China: Walking out the door of my host family's house and locking it behind me without realizing I was still wearing my house slippers. Worried they would fly off, I biked to school barefoot and got lots of looks. My Yeye, (host Grandpa) later noticed my shoes still at the house and biked them to school. I knew he had a lot of concern for me.

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life: When I came back as a real adult. The other times had been in high school and college, and I went because someone handed me the opportunity. When I got here in my late 20's, I realized it was something I actually cared about.

My writing history: I think my best work I wrote in the first grade and was entitled Can't Walk Melissa. It was about a disabled child whose best friend was murdered by her teacher through the use of a "killing machine." Now I'm less interested in child abuse and spend more time thinking about values and the intrinsic assumptions we all make.

Favorite word to use in writing: Turgid.

One word to describe the process of writing: Connection.

Can Rape Jokes Ever be Funny?

Sexist Faux Pas at a Beijing Bar

by Cas Sutherland (scroll to bottom for interview)

A woman takes the Beijing subway to work every day. One day her doctor tells her she is pregnant. "That's impossible," she says. "I've only been on the subway."

When this joke was told to a friend and me at a party, the punch line hung in the air. The young man seemed to be trying to impress us with his… wit? charm? good looks?

I said, “Rape jokes aren’t funny.”

His counter was not an apology, nor admittance that the joke was problematic, nor even a recognition that some people might be offended by it. He said, “It’s not a rape joke -- it’s a sex joke.”

So began a long argument that did little but make me angry and him defensive. He refused to see that this wasn’t an appropriate subject to joke about, as he refused to believe he had made a joke about rape. He did not see himself as someone who would - or could - make a rape joke, and thus the actual issue, the real perpetrator and perpetuator of crimes against humanity - the femi-Nazi, as it were - was me.

How convenient that there were no other men present at our table when he sidled up to share his joke - that he didn’t run the risk of being called out by his own gender for being a creep. Had he imagined that only women would grant him a laugh? Was it painful to him that even a girl wouldn’t laugh at his joke?

Though he was seemingly oblivious to his actions, he was indeed using his gender to assert some level of dominance over we two young women. As though I had never heard such a joke before, he told me I simply did not understand the humour and began slowly to explain it in detailed language for the girl who didn’t “get” the joke.

As if to redirect his listener's fury, he added that part of the humour lay in the stereotype that Asian men have small penises; this was the reason the woman had not noticed being penetrated and thus did not know who the baby’s father was.

While I wished to place the blame entirely on him - it would be much easier to do so as we left the party enraged, primarily due to him - I know it’s not entirely his fault.

Making friends among the lad culture in UK high schools and universities requires a flippant attitude toward both gender and sex. Many young men, like this one, feel they can be blasé about rape primarily because they do not believe themselves or their friends to be potential rapists, and imagine this fact is equally as clear to everyone else. Young women learn to laugh at jokes that undermine and humiliate them, in order to attract and compete for potential beaus.

“It's just BANTER."

I recently had a friend - an otherwise thoughtful, sensitive man - tell me that he felt rape was simply a sub-category of sex. He felt that "sex" as a label covered a whole range of practices that not everyone understood, approved of or agreed were acceptable behaviour. Rape, paedophilia, and sexual harassment would fall under this label. So do polyamory, naturism, and sadomasochistic relationships. It's all "just sex", and sometimes it happens without mutual consent. By his definition, it’s simply a matter of taste and preference; an echo of the Freudian model that rape is the result of individual sexual deviancy.

Yet the Freudian model does not account for the use of violent rape as a weapon. It is used as a part of the standard toolkit in the deployment of genocidal army tactics. Why? Because rape can have far longer-term effects than the duration of the crime.

Rape is commonly believed to be a demonstration of unequal power relations. Rape is not about sex, desire or sexual attraction, but about power: "Rape, properly understood, is more like an injury to the brain than a violent variation on sex. Rape, properly understood, is always aimed not just at the female sex organs but at the female brain." [1] It seems pretty clear to me.

And yet ambiguity prevails. This party guest embraced the ambiguity and even felt empowered to impress it upon his audience. I wonder what that’s like, to see the ambiguity of involuntary sex as good party conversation material. Flirting material, nonetheless.

What is crystal clear to me was muddy and vague to him because he had never needed to see the threat of sexual violence from the same angle. The issue remains a zeitgeist because people - such as subscribers of British lad culture - are uncomfortable to dig in. They are socially rewarded for joking about rape rather than recognising rape for what it is.

"Only yes means yes."

Is it sexy to ask permission? If I ask, will she think me less of a man? What if she doesn't actually say yes? Is she acting like she doesn't want it to make me try harder? Am I in a position to say no?

How many people have felt confused or misled in that vital moment yet unable to ask their partner for clarification? People feel able to play around with ambiguity when it grants them a laugh to serve their ego, but humour fails to solve the issues left by vagaries and miscommunication.

Rape as a crime is defined by the FBI as follows: Penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.

I do not believe that all rape jokes are inherently offensive. Humour can be a great source of healing; laughter is a tool that can aid recovery. Rape survivors may benefit significantly from joking about their experiences; humour allows the freedom to openly express what taboo prevents us airing. There is a degree of truth to every joke, as they say.

But with no previous rapport with his listeners, he had no idea how the joke might affect either of us. He was using ambiguity as a tool to reassert a traditional patriarchal power imbalance that falls along gender lines; his harmless anecdote about male sexual dominance was not funny because it was, however deep within its gift-wrapped box, a threat.

In the words of Naomi Wolf: "If your goal is to break a woman psychologically, it is efficient to do violence to her vagina." [2] Short of committing the physical act itself, a sly rape joke among strangers may serve to slicken the way.

[1] Naomi Wolf, Vagina: A New Biography, 121.

[2] Ibid.

Introducing:

Cas Sutherland

Hometown: Norwich, UK

China timeline:

2013: Beijing; One week British Council student forum

2014-2015: Beijing; English Professor at a Wudaokou university

"Sometime in my first month, on one of my solo wanderings, I suddenly understood that I felt freer in China than I had ever felt anywhere else I'd ever lived."

Most memorable moment from my first year in China: My overriding memories are of things my students have taught me. Particularly when discussing gender, they've taught me things about China I would never have learned otherwise. I think it probably has to be the moment my first-year student, Irene, likened Demi Moore's character in G. I. Jane to Chinese folk heroine Hua Mulan.

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life: Sometime in my first month, on one of my solo wanderings, I suddenly understood that I felt freer in China than I had ever felt anywhere else I'd ever lived. People here wore whatever they wanted, women talked loudly in the streets, children in crotchless trousers squatted to pee on the pavement, and I felt I was able - safe and unjudged - to simply be me.

My writing history: I began writing stories as a child, shifted to writing song lyrics as an angsty teen, religiously kept a handwritten diary of my year in Africa and later blogged daily from a coffee shop in Seoul. A year as a dance reviewer and editor helped me balance a deep love of analytical academic writing; I now write sporadically for a London-based community, an arts site, my personal blog and Loreli.

Favourite word to use in writing: Mellifluous

One word to describe the process of writing: Catharsis

Photo by Wil Wang.

Posted Sept 1, 2015

The End of a Beijing Salon

by William Wang

Zhou Junhua looks over the tattered mess of her hair salon’s stairs, shakes her head once, and then unlocks the door. The glass of the windows and doorframe has all been smashed out, bars and wires now the makeshift barrier. The interior is a dusty shadow of what it had once been. It has been tidied up, but signs of wreckage and age are evident in every corner of the establishment’s three rooms. After twenty years of peace, the last two months have seen four attacks by vandals. Most of the mirrors and windows have been smashed, virtually all of the salon’s equipment destroyed. Zhou extracts her last blow dryer and clippers out of her bag: she now carries them home every night.

Her once thriving salon is situated in Balizhuang hutong, a narrow hutong alley which once bustled with cheap restaurants, shops, and hair salons. But the hutong has recently been transformed into a wasteland of brick piles and dust. The Wuluju apartment building complex is to be erected where this historic hutong now lies, and most of the alley’s residents have sold their properties and cleared out.

A speaker system has been installed along the hutong, loudly repeating announcements for 12 hours a day. A man and a woman’s friendly voices urge residents to vacate the area. “Now, more than 80% of residents have signed the compensation contract. Yet there is still a small group of residents who want to take chances. They expect the policy to change, waiting aimlessly and refusing to sign contracts. We should all know that family problems cannot all be solved by remaining. Agreeing to relocate will change your living conditions for the better and raise the security level.”

The hutong was one of the last vestiges of “old” Beijing, surviving just outside of the city’s third ring road, a hutong where life had somehow escaped the thrust into modernity. But now almost all of buildings have already been demolished, only Zhou’s salon and a few others remain upright in the growing sea of broken cinder blocks.

Development may seem unstoppable, though a few have made highly publicized attempts to do so. Zhou’s salon is not, however, a “nail house” (a home that refuses to make room for development like a nail in wood that refuses to be pounded in or torn out). She and her husband have not once been approached by developers or the landlord about leaving.

It was 1992 when Zhou and her husband opened up shop in the hutong alley, at the time the only barbershop in the quiet lane. But by then, the second wave of China’s economic reforms were reaching all corners of the city and soon after all the neighbors were opening up their own businesses. Ironically, it was also at that time that the State Planning Department announced it was going to redevelop the area. “In fact, the street should have been removed years ago,” Zhou says with a dry laugh.

Zhou found herself suited to her profession, using equal parts hair cutting skill and motherly warmth to build up a loyal clientele. She gave discounts to children, the elderly, disabled people and soldiers. Most of her clients are blue collar men, but the full variety of locals employ her services from young professionals to prostitutes. Her full price hair cuts are still among the cheapest to be found in the capital: $1.60 USD.

Since then, her salon has done reasonably well for itself. Not only has Zhou cut countless heads of hair, she has also trained countless students in the skills of her trade. She built up her business until it had a staff of eight, teaching each employee how more than scissors were needed to succeed in this business. “Sometimes the kids would complain about unreasonable customers,” she reminisces. “So I told them, ‘All kinds of people exist in this world. As someone providing a service, you should fulfill your obligations. You should do your job well; otherwise the customers will definitely be angry with you. Why don’t they get angry with me? I always greet them warmly. This is our principle.’”

And Zhou Junhua’s haircutting skills are as renowned as her friendliness. Her apprentices prove her abilities as many of them went on to open up their own salons or to work in more upscale establishments.

But business has dropped dramatically since destruction became the neighborhood norm and the vandals began visiting. All but one of her staff have recently departed. Zhou wants only to continue on, and many regulars worry about her leaving. Throughout the day, neighbors pop their heads in to say hello and ask about the situation. At dusk, a crowd fills the salon, half of it waiting for a cut, half just coming to chat.

Zhou Junhua’s husband, Jiang Longtan, pulls out an accordion and places it on his knees. “I’m the one that paid for this place so we could open the barbershop,” he grumbles. “I spent 100,000 yuan on it. Now they want us to leave without a penny. Where can we go without the money? Now my wife’s about 60 years old and she can’t earn much money. We’re just not able to leave.”

Since the attacks Zhou Junhua and her husband contacted the authorities but found them to be of little assistance.

“I really don’t know anything,” complained Zhou. “I’m just a tenant. They wouldn’t explain the policy to us. Only the landlord knows about the issue. Apparently, our landlord has already handed in the keys, so the house will soon be taken back. He left without a word.”

“No one has ever said a word to us about any of this,” Jiang affirmed with a grunt, nodding his head to the wreckage about the room. “No one.” Phone calls to the landlord had been unanswered for weeks.

Zhou is unsure if she’ll be able to continue working in her salon for even another week. When her customers tell her they wouldn’t know what to do if she departs, she advises them to find a “roadside” barber who simply sets up a chair by the canal.

Zhou herself is wistfully wondering if she too may eventually resort to giving roadside cuts. Born in one of the poorest of Hebei province’s villages, Zhou Junhua began working after completing five years of school (“I am girl so I was not allowed to continue my studies at that time,” she says, matter of factly), and from there dedicated herself to her business.

“My families say that I’m a workaholic,” she says. “But I just love doing things. I wake up early, clean the yard and greet the neighbors. I have a secret belief that I’ll have good luck if I’m the one that opens the shop everyday.” But now even Zhou feels like her luck can’t hold out.

“I didn’t expect such a messy end,” she says with a touch of resignation. “People come and ask me who smashed my shop, if it was the Removal Office’s work. I can only say I don’t know. In China, it’s said that everyone is equal in front of the law, that there is justice.” She glances at an indistinct point outside of the battered door frame. “But I just don’t know.”

Photo by Wil Wang.

Introducing: William Wang

Hometown: Montreal, Canada

China timeline: William arrived in Beijing in 2007.

2007-2011 - Beijing. Teacher at an international school

2011-2015 - Beijing. reporter, and freelance writer/videographer

'I wanted to tell those kids, "You don't understand your own culture." But then I realized I'd be a total hypocrite, since I understood zilch about my own Chinese lineage.'

Most memorable moment from my first year in China: I once had to take an overnight standing-room-only train ride from Xi'an to Beijing. Highly recommended to try once, but maybe not twice. I was with the rest of the crowd, along with the garbage strewn out all over the floor, across the aisle, in front of the bathroom. After 5 hours of standing, nobody cares anymore. It's definitely a communal sort of experience.

Moment I realized China was an important part of my life: Back in Canada. I worked up north on a rather unhealthy First Nations reserve. High unemployment, alcoholism, family violence and suicide rate. Kids and their parents all hated being Cree. But actually the Cree tribe is extremely interesting with tons to offer. I wanted to tell those kids, "You don't understand your own culture." But then I realized I'd be a total hypocrite, since I understood zilch about my own Chinese lineage. Decided then and there to live in China for a few years.

My writing history: In Vancouver, I wrote for the Vancouver version of the Beijinger for a couple years. Mostly concert reviews, so I could get free tickets. Later i tried being a freelance writer in China, and quickly realized that nobody makes a living as a freelance writer in China.

One word to describe the process of writing: Reediting.