March 2016

Showcasing new writers in China. Last updated March 29, 2016.

He Never Left Her

An original short story by Shannon Adams.

Posted March 29, 2016

“Two-hundred-thirty dollars a month!”

Not kuai – US dollars. He could get a new electric bike with that money, or go to Hong Kong for a few days. He could go to the Happy Valley horse races. Last time he had stayed at the youth hostel and eaten ramen noodles. With 230 US dollars, he could bet on a horse and have a good meal and stay at a hotel on the harbor. Josalyn could come along, but she’d have to pay for her own flight.

“The cheapest option is $120 a month.”

“A-hundred-twenty!”

“Lack of health insurance is the number one cause of bankruptcy. A-hundred-twenty a month is really not that much. Just stop ordering so much food delivery.”

He was 30. Not that much older than 28 or 27. He was healthy. He could get by another year without health insurance.

But Josalyn pressed on. “Beijing’s dangerous. I’ve been hit by a car three times while biking. You don’t even have a helmet. That’s just a ticking time bomb.”

“Well maybe I could get a job that provides health insurance,” he said.

“You could, if that’s what you wanted.”

“I mean, depends on the job,” he said.

“Apparently.”

She was starting to emanate that distant cool. He drummed his fingers along her waist, needing to draw her back in, heat her back up.

“Yes?”

He pressed the small of her back so their bodies sandwiched together. He kissed his own smirk into suppression. He traced her hem until there was no turning back.

The air purifier exhaled. The neighbor’s door creaked open and clanked shut. Someone’s phone buzzed and buzzed again.

Afterwards, her distant cool froze over so fast he didn’t even have time to cover himself. She said, “You should go home. She’ll be wondering.”

“Yep.” He sucked in air through his teeth and jumped out of bed. He grabbed for his pieces of clothing. He picked hers off the floor and placed them on the bed, considerately.

“Turn off the light on your way out.”

“Don’t you want to brush your teeth? ” And wash up, he thought.

“Yeah, maybe.”

“You’ll be more comfortable going to sleep if you do.”

“Whatever.”

He sat down on the bed. “OK, well, see you.” He kissed her forehead.

“Bye.”

She brushed her teeth and washed up. She put her pieces of clothing back on, turned off the light, and got under the sheet. She pulled out her computer and checked her email, her Facebook, her blog. No new messages, no comments. She put her computer away and pulled out her Kindle. She read the same paragraph three times, then put the Kindle away. She lay in the dark and told herself not to think of him.

She woke up some time later. He sat on the edge of her bed, his jacket still on.

“Josalyn.”

“Yeah?”

“I didn’t leave. I sat on my bike thinking.”

“About what?”

“I should get health insurance.”

“What makes you say that?”

“It’s a good idea.” He said.

“Can I say a prayer for you?” Josalyn said.

“Aren’t you afraid it’ll be wasted?”

“No. It doesn’t work like that.”

He took off his jacket and slid in to bed next to her. He stayed with her. For the next several hours, he warmed and salved her heart against its icing. He never left her bed, not once in the days and weeks that followed, even when she daily resigned herself to the office, leaving him hibernating under her Grandmother’s hand-knit ottoman. Faithful through the months, he decayed beside her, the flesh around his mouth peeling back into a crooked smile, as if sneering as she continued to whisper into her pillow, night after night, “God, please light his way.”

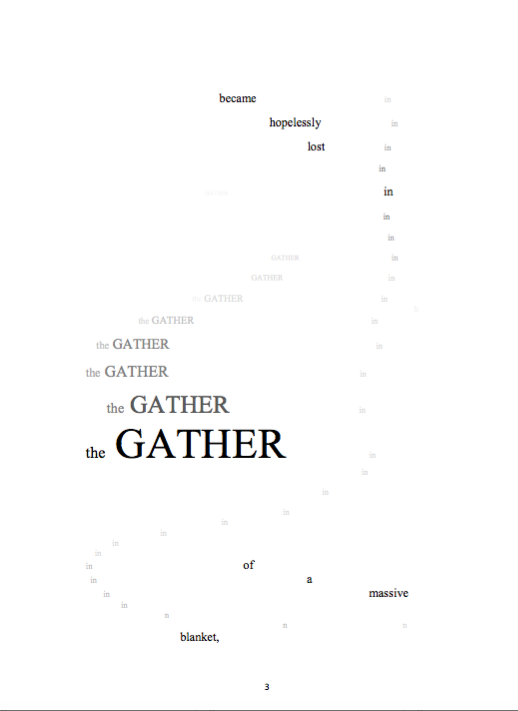

TOUCHPAPER

An original form by Chris Warren

Posted March 22, 2016

1. Explain.

Touchpaper came from the drive to write something protracted and sprawling that had nothing to say and one-hundred-and-one increasingly ridiculous ways in which to say it. I wanted it to be something that could be digested whole or picked-at at random, glanced at and forgotten like a photograph or that would sit in the back of the brain and be subconsciously mulled-over for days afterwards. Whilst I had no target audience in mind when writing and arranging Touchpaper, it was important to me that it was both beautiful to look at whilst also being naïve and childish in a way that might appeal to people despite themselves. Saying that, like all of us who do anything like this really, I wrote it for myself.

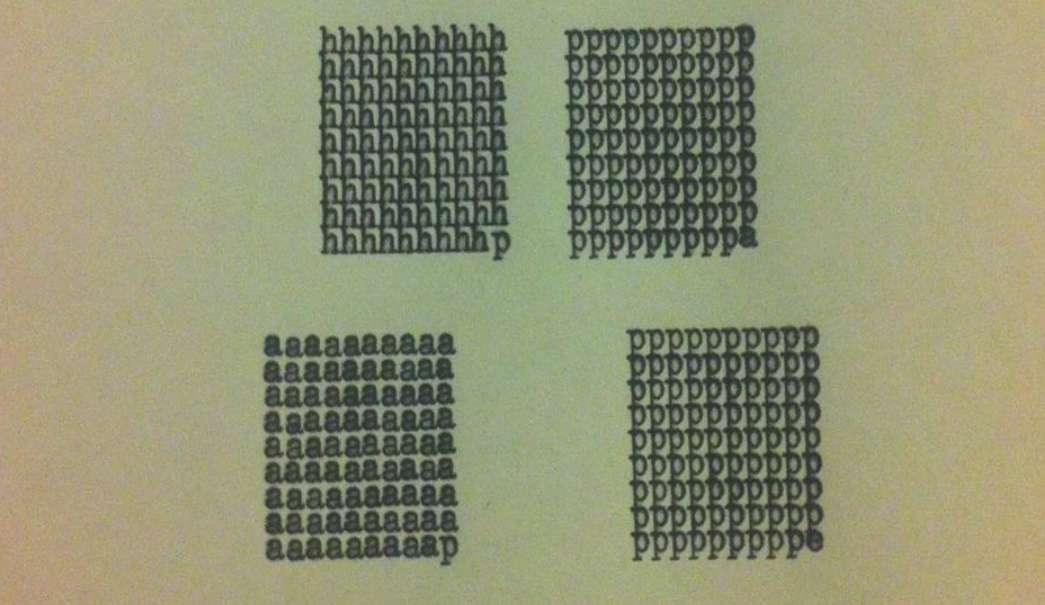

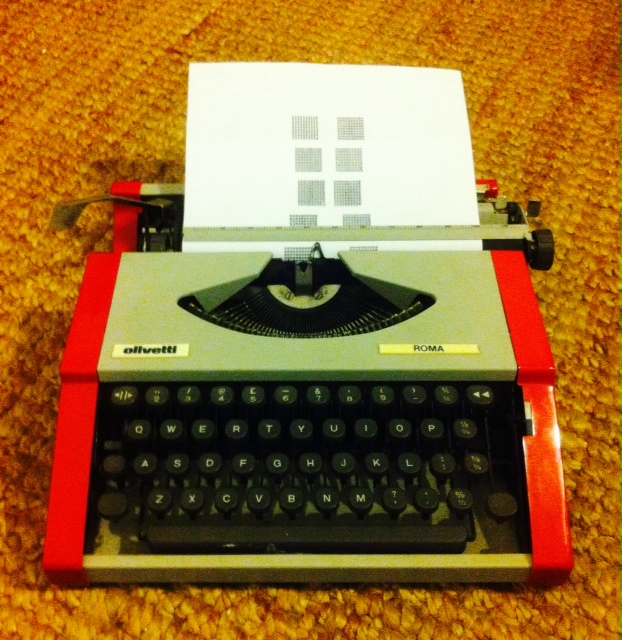

2. What was the process of creating this? (First, how did you start?)

The first version of Touchpaper was just a linear, unpunctuated narrative, and this was how it remained for about two years. I would occasionally have a flourish in which I would add another 50 thoughts (and I still envisage the piece growing over time), but ultimately it felt like a flat failure I was just writing in order to assuage some childish urge. It wasn’t really until last year that it started to become something else, and given the nature of the text, it made total sense for that something else to be of a typographical nature. I had been playing around with typewriter poems for quite a few years beforeTouchpaper came along anyway, so the groundwork had already been laid. Touchpaper, however, was the first real effort I made into putting everything I’d learnt about the process into one (in)coherent lump. I still find it too large a piece to stand far enough away from to see properly, though there’s something I confess to quite liking about that.

3. What were your inspirations?

Oh, the list is a long one; Apollinaire of course; Colleen Thibaudeau; the groundbreaking work of Andrew Lloyd, Alan Ridell, Paula Claire et al back in the 70’s and the more recent work by Ottar Ormstad and Eric Zboya; Beck; Thomas Stronen; Spike Milligan; Dr Seuss; autumn. I’ve been fairly obsessed with the visual possibilities of text for some time though, so Touchpaper was more of a personal inevitability than a drive to emulate my influences.

4. How do you hope people feel or react to this piece? (Or do you not care?).

All I hope is that people do with it what they will, which might sound a bit like I don’t care, but I hope sounds a little more like I have no agenda. I wanted Touchpaper to be playful, beautiful and to have a musicality to it that might appeal to anyone, given a chance, and if even a snippet raises a smile or makes the reader pause briefly, then I’ll consider it a job done.

5. What else are you working on, or what other projects do you intend to start?

Well, I’m back on the open-mic poetry circuit again now, after many years off, so a lot of my brain space is taken up with trying to write things with a performative value, rather than a largely visual one. I’m also trying to shoe-horn some artwork into the weekends when I can, and do very much want to be working on something new andTouchpaperish, but until some mysterious benefactor with an avant-garde bent starts paying me enough to quit my day job, I am only going to have so much time.

Why? And Why Not?

by Sara Huang Xun

Posted March 22, 2016

“Why not”, a very common expression in English, French, and probably many other languages, feels utterly alien when translated into Chinese. It is definitely not part of the vernacular. In fact, one can hardly recall one single instance when Chinese people have used it voluntarily.

I have often wondered about this interesting and telling difference, and how it reveals the latent mentality between the cultures that ask “Why? and the ones that ask “Why not”. The former need sufficient reason in order to do something, whereas the latter need only find no reason not to do it. “Why not” opens up possibilities, prospects that are adventurous, exciting, and unpredictable, while “Why” limits one’s options, connoting stability, practicality, and definitiveness.

The fact that “Why not” does not exist in the Chinese language provides a glimpse into a culture that urges its subjects to always opt for choices that make sufficient sense. Certain characteristics that are perceived as neutral or even favorable in other cultures are deemed rather negative in ours, such as eccentricity, aggressiveness, and “difference”. We have dozens of proverbial sayings to back up this rationale of “playing it safe”. We are brought up on “The bird that pokes its head out first gets shot down”, and “Ignore the advice of the old, and misery will be around the corner”. Through numerous means taking various forms, we are taught to stay with the tradition and hide amongst our peers.

Something that my high school history teacher said in class has been etched inside my mind ever since that day more than a dozen years ago. I remember vividly how self-complacent she looked, as if passing on to us the golden key of wisdom that unlocks all doors in life. “The key to happiness”, she claimed, “is to do the right thing at the right time. That is to say, you study hard now in your teens and get into a good university. In your twenties you think about having relationships and getting married. In your thirties, you work, raise a family, and take care of your elders.” That’s it. I was amazed that life, which already seemed to be messier by the day back then, could be wrapped up so neatly in less than fifty words.

Yet that is exactly how a lot of people live, without exploring, without questioning. Perhaps the problem is not that we ask “Why” instead of “Why not”, but that we stopped asking questions altogether. The Chinese definition of happiness seems to be an endless ready-made list of categories to be checked and rated: school, job, money, house, car, bags, marriage, kids, vacation, kid’s school, kid’s grades... By silently ticking off each box and secretly comparing our list with others, we have indulged ourselves in the roles of mindless travelers merely browsing through life, burying some of the most meaningful questions we can ask about who we are and what we want so deep down in our consciousness that we stopped being aware that they even exist. As a result, certain important concepts in life have shed their rich layers in China, left with a superficial veneer.

Upon introducing my boyfriend, who is French, to friends and family, the most common first response I get is, “Oh, French! He must be so romantic!” Though the French has this reputation of being hopeless romantics, for the first few years of our relationship I never felt that he was romantic in any way. He never bought me flowers, never devised any surprise declaration of love on special occasions, and of course, never proposed.

Having watched dozens of French films and fought with my French guy about a hundred times, it finally dawned on me: It’s not that he’s not romantic. He’s just not romantic in the way that most people in my culture, myself included, construe the notion. We understand romance to be grand gestures, the likes of candlelight dinners, 999 roses, and exotic vacations in luxury resorts. We want the appearance of romance, so we can show that we are happy. As long as our WeChat Moments are filled with breathtaking pictures, nobody cares about what is really going on behind closed doors.

True romance has nothing to do with relationships or marriages, or even other people, for that matter. Your relationship with yourself is the only thing that matters. True romance means being honest about who you are, no matter how unsympathetic the environment is. It means defining your life instead of following rules, no matter how many mistakes you end up making or how much a loser you seem. It means having candid conversations with yourself, and when necessary, looking judgment in the eye and telling it to fuck off. True romance means freedom. It takes so much more than big bucks. It takes balls.

That being said, I’m not accusing my history teacher, the older generation, or anyone else who settles for a so-called “normal life” of being cowards or mindless drones. There are people who truly thinks that a suburban home close to parents is their ideal of a happy life, and on top of that, this nation has

so many good reasons to choose stability over boldness. We are an enormous population with relatively limited resources, and our national memory is instilled with a constant sense of insecurity and fear that life can be upended overnight, out of the blue, and for no good reason at all. In our days and time, this fear has been gradually diluted as it passed down from generation to generation, but it’s still there, stubborn, unyielding, forever warning against the lure of straying from the beaten paths. My history teacher meant well, like our parents and anyone who generously offers advice on how to conduct a life as smoothly and safely as possible. Don’t ask questions. Don’t think too much. Thinking and questioning leads to mistakes, and who knows which mistake will put you out of the game?

It is curious how a people so bent on practicality and utilitarianism often laments on our lack of imagination and creativity. It almost feels ironic, if it’s not so profoundly sad. What’s the use of imagination if you don’t believe it can make a difference? What’s the point of creativity if it will never materialize into something you can enjoy? How are we supposed to mature when we are pressured to make commitments before we have a chance to explore our possibilities? As long as these questions remain unanswered, the “Chinese Dream” that we so much want to indulge ourselves in will remain an empty shell, a golden shell maybe, studded with diamonds, but with freedom forever missing as the centerpiece.

I long for a future in this country where our children can ask “Why not”. Why not stay in a tent instead of a five-star hotel? Why not buy an RV instead of an apartment? Why not enjoy being single if you haven’t met someone you feel comfortable spending your life with? Why not skip kids and focus on your career if you feel like what you create, be it a company, a book, or a building, says more about who you are than a couple of screaming and whining little things. (For the record, I like kids, but I have to portray them as screaming and whining little things for the sake of the rhetoric.) Why not be gay and celebrate it? Why not be a freelancer and work outside the box? Why not ask questions and explore answers, or the lack thereof? Why not make mistakes and find out who you really are in spite of what everyone else says? Why not take a chance, and say “Why not”?

Introducing:

Sara Huang Xun

What's your story?

I was born and raised in Shanghai. Did undergrad in Beijing (with one semester exchanged in Hong Kong), Master's in New York, and then moved back to Beijing. I've never lived in France. I have tried studying French, three times, but always gave up when I came to the "conjugations". So technically I only speak Mandarin and English, but I also know a little bit of French and Cantonese. I'm currently working in film. I'd like to think of myself as a producer in the making.

Are you a debater?

I guess I am, but as I grow older debating starts to seem pointless.

What's more important, being right or being convincing?

Neither is as important as feeling convinced.

What inspired you to write this piece?

Having been caught between cultures and having to fight off a lot of the "brain-washing" that was instilled in me while growing up, the "Chinese way of living" has been a constant subject of contemplation.

You are unique as a multi-lingual Chinese person. What is the big difference between knowing 2 languages versus 3?

Every language opens up new perspectives and new worlds. One more language, one more angle to look at the world and life.

I imagine you have many insights into cultural and linguistic differences. What are some other topics you may write about in the future?

Relationships. Women/Gender. Identity. An idea just occurred to me: It would be interesting if you have a westerner listing things he/she finds bewildering/shocking about China and me trying to explain everything. (Haha. Fun!)

As We Go, So Goes in Fulton County

by Samuel Geiger

Beaty, Il

So many of these roads are just the in betweens. What a pity we don't revere cornfields as we do the black sky. Roy struggles to light his cigarette against the wind of the open window. The van slows on the hills, pulls through shadows under summer lit trees. Here, scattered farms. What buildings there were now feed the grain. Roy asks if a place is still a place if you're just passing through. I say, we're all gonna die, idiot.

Bybee, Il

Fields of soy, the truest green. We putter over a pathetic summit: a vista of farmland, dense forest. So flat: in the Midwest, the sky plumps like grandmothers. We rush into the scenery, Roy's phone says this all used to be Bybee. We pass an intersection, houses stand crumbling on two corners. We drive further down the road to see a dirt path lead uphill. Roy laughs, oh, of course. He muscles the van off road and we rock up the uneven path; come to a clearing, we get out of the car. Roy pulls a blunt from behind his ear to play it around his slender fingers. We amble. He replaces the stick behind his other ear; in the sun, we've both become pink. Downhill, we walk towards a cropping of trees. A taut band of black elastic hugs a little green box to a thick trunk. Roy drags the blunt and tells me, that's a camera. He turns and hikes back to the car. If Bybee is supposed to be uninhabited, who's watching us?

Farmington, Il

Trim yellowed grass along a long road. On the left, open field; open sun. On the right, the railroad runs parallel. I wonder if Roy's lost before I realize that that would mean we're both lost. Flocks of crows roost on barren trees. Miles away, vultures. Empty towns have their own kind of quantum presence; there was once a time when each of these stalks of corn could have been a person, standing. Roy sees the memorial plaque. We pull into the driveway; the train tracks disappear on either side: to the right, Chicago, to the left, whatever remains. Off the highway, there is wind. Roy and I go to read the plaque. Here, there was once a train station and a large general store. People would come, drink on the porch. People would gather to smoke cigarettes and watch the stars come in. Roy scrambles up the ditch and hops onto the train tracks, the boy's got some broad shoulders. He turns and says, well, I'm off to Chicago. I watch as he begins to walk north, shards of glass flash in the dirt. I hike up to the tracks, too; I bend, remove an iron spike out of the wood. Roy turns to me, far away. The spike has rusted for as long as it’s been stuck in the tracks, heavy. Of that life, only under thunderous metal and passersby. Roy returns, I say, welcome home. He lights another cigarette; we lean against the trunk of his car and listen to locusts.

Bernadotte, Il

Roy smiles as we pull into Bernadotte. No ghosts here: there are people, a cafe named after the dead town, a park aside a murky river. Downstream, a rusted bridge has collapsed into the water. Our hands brush, the sun is beginning to set. Along the riverbank, dead fish dry in the sun.

In a cornfield near Abingdon, Il

The wind licks all the leaves. Loud droning, crickets nearby. I wonder for how many years this field has yielded corn, out here in the in between, rows and rows and rows and us, we sit erect, mock the corn. I tell Roy that this might be the center. He opens his mouth as if to say something and oh, isn't it strange, the gravitational pull of empty spaces.

Polywater

Madeline closes her eyes and dips back. The sun cuts light on her breasts, emerging out of the surface of the water like apples. She tells me that, floating, she will never be lonely.

My body slips below and lower, the increasing pressure indents my flesh like a swaddling blanket. Green lake, surrounded by forest; under me, a black hand of algae, above, six kicking legs, three asses suspended like young leaves falling, ferocious light sneaking past the surface. Swimming in a between world, like lifted up on wire for so long; down, seaweed licks my ankle. Mouth bursts open, the plant grabs at my shoulders, he shaking and me yelling, drifting in a passing current. No fear of the water leaking in, only afraid of being left behind curled fetal in a broad green palm. My arms drive me to the surface again.

A car emerges from the trees, up the gravel path. Two friends step out, they are lovers; through branches, I see them kiss. Victor carries with him a sagging plastic bag; they've arrived with fresh fruit! They saunter down to the dock. Under their weight, the wood bobs in the water. Victor reaches into his bag, Hey! he yells. Hello! I yell, wave. He removes a fat apple, winds up, launches the fruit to the sky. Morgan laughs. I say, Wow! It crashes next to my head, swallowed by the lake, reappears behind me. I palm the fruit, bring it to my lips, bite into it as if I were trying to tell it something.

Sanna paints our faces. She drags her brush under our eyes, along our lips before she blows our faces dry. Sanna projects on us, we’re like movie screens, like secrets shared in color. Earlier, in Sanna’s car, we catch hands. As we chew through the browning cornfields, she looks distant, caught between a threatening palm and the light raining down. Sometimes, it feels like you're breathing and there’s the world; other times it feels like the world’s breathing and there’s you. Madeline sheds tears, wet images muddy along the curve of her nose.

We move to the dock, we peel off our clothes. On the opposite shore, branches spread out from their trunks, fold like fingers and twist, bend unto one another. In the canopy, birds pick at berries. Madeline says, I hope you guys don't mind a little nudity. When we laugh, our naked bodies show it: all bulging muscle and moving fat.

I dive in: when I pull up from the water, I feel the sun reflecting off the faces of the waving people on the dock like a firm slap in the ass.

Madeline dives in: when she pulls up from the water, she breathes in and she can't stop screaming.

Untitled

In 1982, Brenda awoke unable to peel off the sheets. Quadriplegia, I imagine how this is just an extension of the life in waiting. I do not know how long she waited on that morning for someone to come draw her from her bed. I didn’t ask if she screamed. Doctors plied her open a week later in a live autopsy, more time in a bed that doesn’t feel right because she doesn’t feel anything.

I met Connie at work. We talked about motorcycles, she told me about the rides she took. When Connie would short her cigarettes, she hid them behind her ear, often would forget they were there, sometimes would carry a short behind both ears and a third long, white Crown in her mouth. Connie tells me that, on her and her mother’s farm property, a goat still roams the grounds, despite her sick mother having moved into town years ago. I ask where the house is. Out that way, she makes a wide gesture south, The roof’s caving in, the fields’ve turned to shit but at least the goat’s loyal.

Connie tells me that now her mother stays mostly in bed in her room in her townhouse where fluid pours from her leg.

When she wakes in her sore bed and cannot feel chill, it is March and Illinois is stuck in a winter that wouldn’t end until April. Snow drops out of the sky, slow against the window. Brenda reasons with the doctors, says something is stuck inside of her and since 1982, the men in coats have taken from her.

They remove a lung, muscle tissue, nerves and skin; they assemble from the pieces ripped away. Connie drives Brenda to physical therapy in her first white pick up and though the skin that remains leaks and bleeds and bruises and maps by so many scars, she walks again.

At work one day, Connie brings me a book of poems her mother wrote. I read them all on that afternoon, as soon as I clocked out. Life passes like the falling of night; the body is the only thing warm enough in a blizzard; the house in which Connie and her other children grew up will soon be swallowed by corn. Brenda doesn’t believe in her own mortality.

Another morning, another list of places on her body with which she has again lost contact. In order to do it again, drag her feet along the floor, experience life in motion, Brenda begins to save money for what she calls the stand-up machine, the new plan to walk. In 1984, the vasculitis begins, liquid streaming out of her like a dam broke. Brenda's knees buckle. She spends the rest of her life in a wheelchair.

Connie tells me that Brenda’s the type of person to show you her bed sores. At this point, I don’t think I understand the reason to live. In her writing, Brenda insists that loving someone is a cosmic event and I think I agree. Despite her life past, despite her head having already collected the only pieces that still move, Brenda laughs, tells me the past is as real as you want it to be. I hope that this is indeed a way to live.

She tells me that her body’s always been trying to die. In a hospital bed before they were such needed, Brenda lies on her back, crying and screaming; giving birth to her second child. She tells me that the pain of the body’s expulsion is so dense, that she feels that her entire life orbits around those four experiences. On the bed, the first time they plan to make crater her body, to open a hole not because her body is killing her but because her body is killing someone else. Inside her, the baby turns blue, just seventeen and the poor girl already knows the untrustworthiness of her own body.

Doctors barking like dogs, unbelievable shrieking and a big window filled with slow, solemn snow, ironic in that this is the worst way to count the minutes but true in that during moments of such calamity, warmth flows from silence.

The chord tightens around the neck of the infant girl, her tiny head blue and bluer and out in the hallways all the nurses clack high heels on tile and this baby is going to die, doctors say, Brenda, this baby might die and Brenda only expels her breath, feels her body strong and slim as it was back then, she expels her breath and thinks of the way the children grow up and how already her first daughter’s lips spill all of the kind words that she will never have time to say.

The doctors still yelling, Brenda almost brought to convulsions: 'she's dying, she's dying!' before they take the knife to her stomach; no anaesthetic, seventeen and opened for the first time, 'she's fucking dying!' Piercing and slicing, searching for the beating heart inside of her, skin of her belly and then her womb and then the blue baby, 'here she is, here she is!' A flash of the gasping child, wet, and then Brenda’s heart stops, the baby’s heart stops, the pair of them stray, waiting around.

That’s all there is, a flash of the blue baby, heart stalling, and Brenda’s in a coma for eleven days. Closes her eyes, the baby’s heart replies, thump thump.

Egghead

Your dad's head looked like a fat, white egg and he passed that trait to you, his only son and child. Do you remember the time when you were coming in from the beach up in Michigan, walking towards those A-frames, those shitty A-frames you always talk about? You got up to the deck, the old wooden planks spanking against your adolescent feet, and your Nani, your dad's mom, sunning herself in a reclining lawn chair, greeted you like she always did. She lay her novel, Forbidden Fruit, against her chest to talk again about what children, 'What children!' you will have, someday, someday. She talked and talked until you got so thirsty that you bent to get a drink of water from the hose underneath the A/C exhaust box but you folded too quick and you smacked your head hard on its sharp corner, the hit reverberating and humming, the metallic sound of which, you thought wrongly, was born out of your own head. You stumbled around, your balance confused. "Nani!" you say, a viscous red crowning atop your head, "Nani, I'm bleeding!" you yell, right before you hit the ground. You fell over and pounded the battered wood of the deck and your vision blurred but you could feel the noodles and floaties that were standing up against the wall fall over you in rainbows and rainbows of foam and inflated plastic. Your head opened up like an egg and wet all over that nice wooden deck when a baby started wailing on the beach. Your dad came out: fat and clueless and standing next to your body collapsed beneath the life preservers and looking around wondering what to do because there is no mother and so he just scooped you up like a bruised apple. He plucked you up off the ground, not tenderly, not gently, but he heaved you up and carried you, your limbs lanky and dangling, your insides leaking, emptying without even having been full in the first place. After falling asleep that night, you dreamed of rotting.

shrapnel

when everyone flew out of our small midwestern town for the summer, i remained behind among scattered few, left out of context. i wrapped my weed in passages torn from a gideon bible, watched the corn grow. beginning of july, it got tall for that time of year; wasn't until september that they razed it. i used to go to the graveyard after work to write letters to far flung friends, never ended up sending a single one; barely wrote any anyway, instead just watched the sun collapse into the rail-yard. half in a hashdaze, i rarely thought of anyone but a man who, in april, i thought i would love forever and how under such pressure again and again the body chooses to bend around another. i worked as a painter, spent days brushing over small stains on the walls of dormitories and academic buildings. a few other stranded students worked together with the school's cafeteria ladies. we didn't talk too much but on our three daily breaks, the students filtered away from the ladies. we spoke, a new puzzle to solve, and on the hottest days, we climbed to the astronomy deck, smoked pot on the roof, the old kings burning away; even surveying out from up so high, we never saw where the town ended. at night, we got drunk and laid on grass asking hit me hit me hit me and on weekends, we'd drive out to the prairie, to the river. swimming, we would dip our ears beneath the water, close our eyes to float away on our own, birds diving under clouds. i remember once we all stared at hawks turning in the air, a vision so holy that we couldn't bring ourselves to crawl out of the water until long after they flew past and it was cold and we were shivering, the stars rolling in. we scampered up the wooden ladder onto the dock and all of us were too afraid to touch any skin. then came the day my apartment's lease was up, i packed and stored my things, vacuumed the carpet and this was work. that night, the full moon on its way, i dosed eight seeds and lowered into a hammock, thought if i tried i could find god but the only thing i found was how badly i need him. no god, just a crater shaped by how incredible it is to watch your lover's long limbs flash descend branches in a tree, to sit on a yellow porch with your closest friend talking and talking and smoking cigarettes until your teeth hurt, to emerge from the water again. middle of september, everyone flocked back. the corn finally fell and i went walking through the fields: in the flat land, the tallest thing around for miles and miles.

Introducing:

Samuel Geiger

What's your China story?

China has always seemed like something of a dream. I'm sure we all say that, you know, like we can see Guilin peering through the smog. I study Mandarin at Peking University where we aren't allowed to speak English during the week. I've had some difficulty with this, partly learning to speak Chinese and partly learning to not speak if I have no way to say something. I don't remember, however, this much fearing being inarticulate as a kid. I love it here, have you had the duck yet?

What's your life story in less than 10 words?

Played videogames for so long blood condensed along my brow

A metaphor to encapsulate what China is to you, in your life?

The other day I went to the gym and I waited for 25 minutes to get on a god damn treadmill. Can you believe that? It's just that busy, there are that many people here, I guess. I finally hopped on the treadmill and just thought that it seemed so much like what our descendants are going to have to deal with. China felt like more than the future then; to me, China is the ship on which we will all one day have to leave the planet to find a new terrestrial home and for those thousands of years with no dirt underfoot we're all gonna have to wait a half hour before we can get on the treadmill.

Your writing history?

I always wanted to be a writer, I've always loved books. Never felt compelled to write my own stuff though until The Picture of Dorian Gray blew my head off. Then a couple of years later I read What We Talk About When We Talk About Love and I learned about what isn't important, namely, ya know, most things and so here I am arguing with myself about why Facebook wants me to run my cursor along it.

What are your common/recurrent themes in your writing?

Moon, wind, temperature, men I've loved, boys that made me sad, what I'm doing to myself, why I'm doing whatever it is I'm doing to myself, water, friends sweet like fresh fruit, what it is to be a person now that you know all about me and I could easily find out all about you, incense, climbing trees, Illinois, missing my brothers. They're varied.

What happened in your childhood that inspired this?

Childhood happened, the suburbs happened, it's hard for me to talk about specific events in childhood because I can't see them as separate from myself, the person writing. Go to Illinois, I've never seen for so long in the flatland.

Any notable projects you are working on lately, or hope to start soon?

I'm working on two or three different long form poems and a novella right now. It's hard to live in China and not constantly obsess over what time means. That's what I'm writing about now. The novella is about time in the way that its passage in our external lives does necessitate its passage in our internal lives as well despite my own hesitations and doubts, its about the alien way light manipulates the smog surrounding the advertisements that glow, its about auspicious red.

Advice for other writers?

Write, dude, poetry's a trap and you're not trapping anything if you're not writing.

READ ARCHIVE

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.