Showcasing new writers in China.

Special Edition:

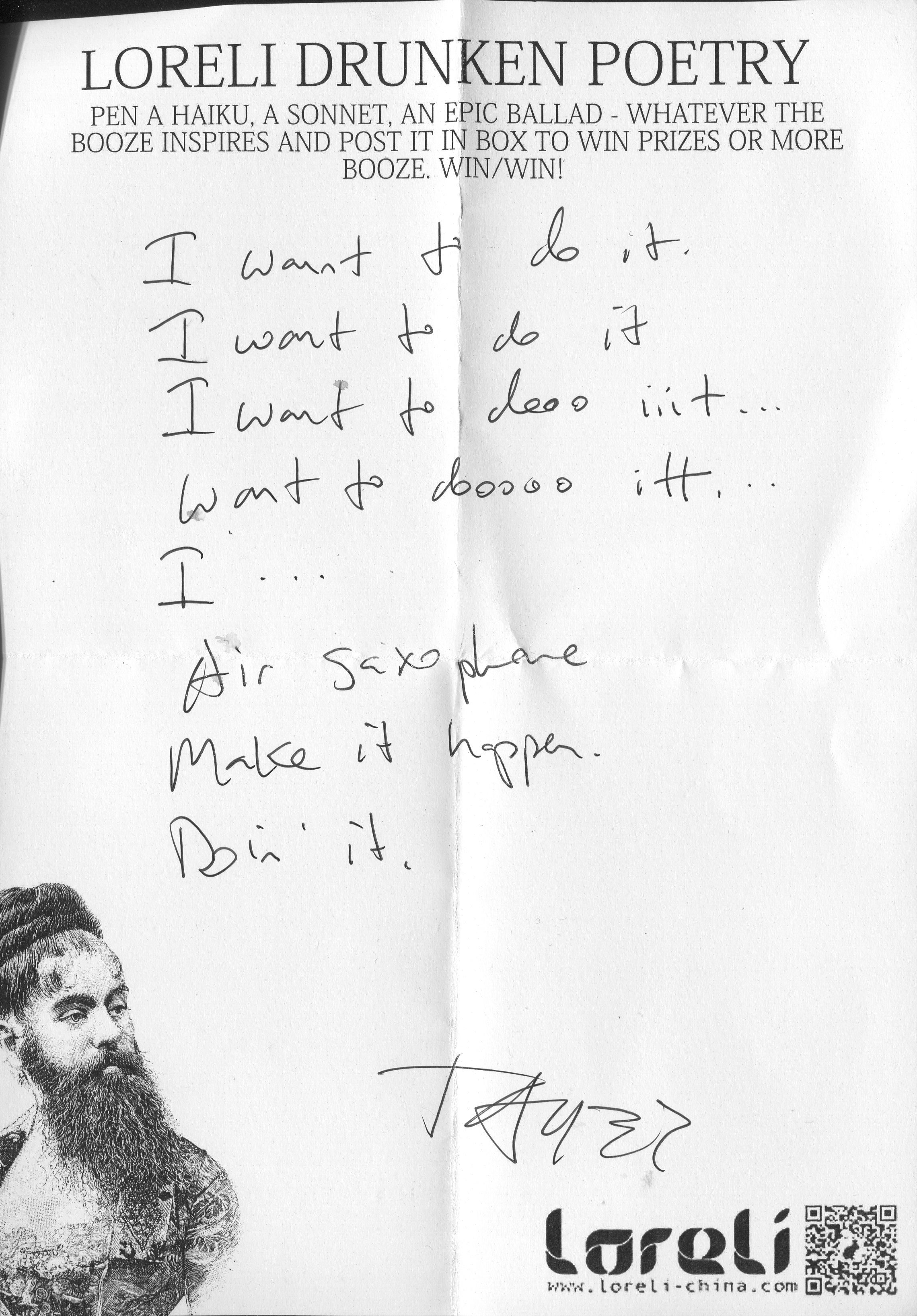

Drunken Poetry

Gettin' high and low with dragons

Last year, at the Loreli launch party, the three original ladies of Loreli hosted a segment that turned out to be a smash hit: drunken poetry. This year, we brought the crowd favorite back and got some pretty damn good results. Take a look!

Judith and Anna making it funky one dum at a time

sending vibes - that's what drunk poetry is all about

hehehehe hehehehe

And the legibility continues to decrease at an exponential rate...

20 Qing's for 2 Dao's

Is someone drunk?

It's never what I think it is, is it?

Now onto the gags. Prepare yourselves!

Oh Amy, you graceful so and so

There's a story behind this one, I promise.

Since Loreli started, we've received an (almost) overwhelming amount of attention from certain individuals in the form of dick pics. Very classy. So at the party, longtime Loreli friend, menace, and in-house makeup artist Kelly composed this highly conceptual poetry/visual arts mash up for us. Thanks Kelly.

LORELI LOVE

And boom! Due to limited space and loss of certain poems because someone got too drunk (oops), we can only feature a selection of the fine, fine poems from the glorious night that is last Friday. Huge appreciation for everyone who participated and made us laugh like idiots on stage. Best drunken poems I've ever read.

2 Poems by Caleb Washburn

Back from the the holiday with new work from Caleb Washburn. A a poet from Kansas City, Missouri, Washburn received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh. His work has appeared in, or is forthcoming from, The Atlas Review, Bat City Review, Fairy Tale Review, The Journal, The Laurel Review, and Vinyl, among others. He is the managing editor of the online journal Twelfth House. His work is definitely worth more than a preliminary google, so follow those links and keep your eyes peeled for the relevant journals. You may also have the good fortune to catch a live reading at a future Spittoon (keep your ears open).

A q&a follows the work.

-

The Ground Cannot Take Me

I sang the news of the day

but no one thought it beautiful

We don’t want requiems

I sang them too poorly

I am a thing of the air

and dark and low

But still I just want one day to sink

deep into the ground and turn

my sight up to the sky

Yes, that’s it

To love something but not need it

(I have always been so bad at this)

To squint when looking into the sun

or at a cute boy as blinding as the sun

It is so hard to still want something

to find it desirous when looking

at it head on

I have been a god all my life and lonely

Nothing can prepare you for that

-

Love in the Era of Drones

1.

We do not flock. We do not forage. Fish shoal. Insects swarm. I’m not going to say I’m jealous, because what is jealousy but another motivation I don’t need. What I’m saying is you’re better off with me and I’m not standing still.

2.

Shirk the 24/7 lifestyle because it’ll never get it done. My nights are more about a kind of resilience than empathy. I read The Times subliminally and you are too old. You need a penchant for the absurd which you build up like a thick skin, a second skin you wear like pride of country, pride of knowing. Be proud of me and I’ll show you all the places nobody knows about—the rocks I’ve hollowed out in the middle of empty fields, the caves that wait like tongues for water.

3.

There are more ways to lose your lover than ever. There are more ways to love your losses than ever. These are songs as old as gypsum, as cold and smooth as alabaster. Sing me the new shit and I’ll go all filibuster. My lover loved him some destruction ‘til he died.

Q&A

MB: Let's talk about the drone stuff first because that seems to me like a self-contained mode. What brought you to drones? And if you were chewing on American-foreign-wars stuff, what makes drones particularly inspiring to you?

CW: Ever since I was a kid I loved photography, and even removed from the militaristic frame of drone cameras, the camera and photograph themselves have always been able to awe me. I always attached a kind of mystical quality to just the camera itself.

But then you attach a camera to a device that can fly at silent and invisible heights and be able to capture in absurd detail the huge tracts of land it is flying over, you film in infrared so they see through buildings, and then you attach to that missiles that are accurate to a shoebox, and you control all of this from the other side of the world via satellite, and like this was all very terrifying to me like way before I got to the missiles.

But I don’t think my poems actually do a very good job of engaging with the political or militaristic implications of drones all that well. Instead, I’ve used talking about/through drones as a way to tap into a kind of fervency.

The first drone poem I wrote was a retelling of an Old Testament story, of when Isaiah becomes a prophet, and ever since I’ve been interested in writing about drones as a way to tap into that kind of pitched up, intense lyric, where a celestial being can place a burning coal to your lips and call it a blessing. (I also can’t think of a better analog for America’s foreign diplomacy, and its spread of democracy through bombs, than calling a hot coal pressed against lips a blessing.)

MB: Is there a right and a wrong way (for you) to do politics in poetry? (Or is all poetry political?)

CW: To answer your second question first: in the sense that, yes, all utterance has political implications, yes all poetry is political. But I think that’s a side step away from you first question.

Yes, there are definitely wrong ways to write political poems. I am also not an expert of any kind on the matter; while my drone poems definitely have political elements to them, my experience with drones is entirely theoretical. Instead, they are a way for me to get at something else (this kind of religiosity, fear and dread, a speaker who sees themselves at times as being godlike, etc.).

However, all that being said, what I do know about not writing a bad political poem: your / your speaker’s positionality matter, and you need to be aware of how you’re positioning your speaker. If, for instance, you’re writing about the 2015 Tianjin, China explosion that killed over 170 people, but your speaker is an expat in Beijing who keeps ominously referencing the smog and his concern for his safety as an expat, then you’re missing the point. When the poem can only filter the tragedy through the speaker’s perceived lack of personal safety, it fails to engage in the weight of the event itself.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, I want to point to Solmaz Sharif’s poems; in her debut book, Look (Greywolf Press), she also engages the topic of America’s drone warfare, but does so in a way that I think is far more successful than mine as political poems. The reason I think they are successful as political poems in a way that mine are not is that their heat, their oomph comes from making the weight of America’s political decisions actually felt. Whereas my poems are interested in drones as metaphor, Sharif’s poems give glimpses into the lives of those effected by this warfare.

MB: As someone who writes about drones (whether they're on the periphery or at the center of a poem) has living outside the US changed the way you write about living in the US (or do you not feel like you write about living in the US)?

CW: The poems published above were written when I was still living in the US. I haven’t written any drone poems since moving to China, but I had also stopped writing them in the couple months leading up to my move. I don’t think the move caused me to stop writing about drones, but instead I just found new ways to obsess over the same kinds of ideas.

Yes, moving to China has changed my writing. While I’ve done a decent bit of writing while here, I’m still figuring out what it’s doing. I don’t think I can really say more about it, though. I usually need a lot of time separated from my work before I can kind of get a feel for what was going on with it.

MB: I love this line, which I consider the non sequitur equivalent of the rabbit punch: "I read The Times subliminally and you are too old." Also love this triple-decker simile: penchant for the absurd [is like] thick skin [is like] pride of country. Is this the primary function of the absurd? (To protect us.) Another way to read this question: what's the function of the absurd?

CW: Keep up.

MB: I'm not sure the poems we're running today on the site are representative of this but I love your body stuff, man. You treat sex like a mystic and I'm not used to hearing that work, but we crave it (a mystic approach to sex). There's always a tension (contradiction): sex is "just" sex and not important compared to some other thing, but the sex drive can also strand us in strange places, amazing places or terrible places. If I had to twist this into a question, it would be: when you write about sex or the body, do you feel like (as a poet) you are processing your own feelings, or like you are building something consciously (outside your own life)?

CW: When I write about sex, I’m not writing about my sex life, or even my sexual interests. I think if I were to, that would be really boring. For me, sex is just a situation that I can superimpose other ideas over. A recurring obsession of mine is desire or longing, and masking different kinds of desire as sexual desire has seemed pretty fruitful for me.

MB: Another thing that keeps coming up (here we see it in The Ground Cannot…) in your work is a dispersed personhood, or a person wanting to be lots of places he can't be. If I got the title here, you're adding that the longing to "sink/ deep into the ground and turn/ my sight up to the sky" is not realistic. Have you figured out any secrets for getting out of the human body or are we pretty much stuck here?

CW: I really like that reading of the title, as a kind of refusal of the ground. “The Ground Cannot Take Me.” Huh. I’d never thought of it like that.

Unfortunately, “sink[ing] / deep into the ground and turn[ing] / [our] sight up to the sky” is all too realistic, in that it happens to anyone who has a common casket burial. Or is that fatalistic?

MB: How has your poetry changed since you started writing poetry?

CW: I don’t know, I’m still very much in my early writing stages. What’s changed is that I’ve read more now than six years ago.

MB: What are you working on right now?

CW: I really can’t say, although that’s not me just being oblique. I’d describe it, though, by saying that my lines are getting longer and are becoming slightly more aphoristic. I’m a little more interested in the unit of the sentence, rather than the line (which might mean I’m writing prose??). The poems also feel more emotionally vulnerable, which is what scares me (so that’s what I’m pushing towards hardest).

MB: Read anything cool or terrible recently?

CW: I’ve been reading a lot of (and about) Anna Akhmatova, the great 20th century Russian/Soviet poet. I’ve been reading the new Black Panther comic series written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and I’m waiting to get my hands the spinoff World of Wakanda comics, which will have issues written by the poet Yona Harvey.

It’s a little tough getting my hands on the new collections of poetry my friends in the States talk about, but I’ve made sure to pick up Solmaz Sharif’s Look, and Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds, which are two debut books that set the bar so high.

READ ARCHIVE