Showcasing new writers in China.

Short Fiction by Nick Baxter

We return from our special edition, sobered, with this short story from Nick Baxter. Nick grew up in Scotland and the north of England. He studied chemistry at the University of Edinburgh, and has stumbled from one thing to another since. Most recently he has been involved in international development work. He is currently looking for a job, if any UN agency types are reading this. I'll withhold further comment and context for now, as a q&a follows the work.

Lanirano

The village had a name, but in our story, the story we’re telling now, it doesn’t matter what its name was. This is the story of how the village got its new name, the name it has today.

The village was by the sea, but you couldn’t see the sea. You could hear it though, from the other side of the sand dunes. Have you heard the sea? The sea made a noise like a motorway, although nobody in the village would have known what a motorway was, because this all happened a very long time ago when there weren’t any motorways.

(There still aren’t any motorways in that part of the world. But the sea is still very loud on the other side of the sand dunes.)

There was a little girl living in the village and her name was… Well, let’s say that her name was Samantha, like yours. She lived in a house with her mother and father and all of her sisters and brothers. Her father was a fisherman and he fished from a small wooden canoe made from the trunk of a palm tree. Samantha’s house was also made from palm trees. The walls were made from the trunks of palm trees, chopped into pieces and nailed together, and the roof was made from the leaves of palm trees, all dried out and tied together with string. Often her father stayed out fishing until late at night and Samantha would stay awake and wait for him to come back safely. When she lay in bed at night she could hear the sound of the sea on the other side of the sand dunes, like somebody breathing out but never breathing in. (That’s what a motorway sounds like, too.) And she could hear the wind in the bushes around the house, like somebody telling her shh, shhh.

Samantha’s family wasn’t very rich and they lived at the unfashionable end of the village. If you walked up the sand dunes until you could see the sea, you would be looking at a big beach that curved around almost to the horizon in either direction. Put your arms up like this, as if you’re trying to stretch them around an old, wide tree. That’s what the view looked like! Imagine that your arms are the beach. See how they stretch out into the distance? Between your arms is the enormous blue sea. Running along the top of your left arm, like this, there are mountains covered in jungle. Now look up. In the sky there are only clouds and birds. No aeroplanes.

Wait, don’t put your arms down yet! I was telling you about where Samantha lived. If you walked out of the village in this direction, along your left arm, where the mountains are, there were lots of other villages. You could walk for hundreds of miles up the coast and meet lots of people and see lots of things, like a tree that lives for a thousand years, or a type of monkey with a magical finger. But if you walked out of the village in the other direction, the sand dunes got very big and you came to a place called Many Bones.

In Many Bones there was a poisonous tree with a deadly smell. When the wind blew from the south, all of the people and the birds and the animals to the north of the tree died. And when the wind blew from the north, all of the people and the animals and the birds to the south of the tree died. All of their bones collected around the tree, so the place with the tree was called Many Bones. (You can put your arms down now, thanks.)

Nobody wanted to live too close to Many Bones and the poisonous tree, so the end of the village where Samantha and her family lived wasn’t very popular. Every morning her father would get up early to go fishing and when he stepped outside their house, he would take a deep breath and say ‘Mmm, smell the salt in the air. It’s a good day for fishing!’ The neighbours would stare at him, because they thought that perhaps the air was a little bit poisonous from the tree in Many Bones. But Samantha’s father didn’t care and so Samantha didn’t care, either. Every morning she would take a deep breath too, and she never dropped dead – not even when the wind was blowing from the direction of Many Bones.

One very hot day, a stranger came to the village. He was a very old man and he walked into the village from the fashionable side, because he had come down the coast, through the other villages, from somewhere very far away indeed. Perhaps even the place where they had the one thousand year old tree, or the monkey with the magical finger. There wasn’t a road in the village, because they didn’t have cars in those days, but there was a little track that led to the next village. That’s the track that the old man came along. His accent was so funny that you almost couldn’t understand what he was saying. He was obviously very poor, because he wasn’t wearing any shoes and his clothes were almost rags.

The first house that the old man came to came to was Mr and Mrs Smith’s house. Mr and Mrs Smith bought some of the fish that Samantha’s father caught and they traded the fish with people from the next village for all kinds of interesting things. Mr Smith was rather old and Mrs Smith did most of the trading. They had a big house and kept a couple of chickens. When the old man arrived at their house, Mrs Smith came out to see who it was. She was wearing an elegant, multi-coloured straw hat.

‘Yes?’ she said. And ‘Have you come to trade?’

The old man told her that he didn’t have anything to trade, but please could he have a glass of water?

‘I’m sorry,’ said Mrs Smith, rather coldly, ‘but we’ve run out of water.’

The next house that the old man came to belonged to Mr Jones, who was a fisherman like Samantha’s father. Mr Jones was a very successful fisherman. He was so successful that he didn’t need to go fishing very often. Instead, he owned several canoes and he would rent these to other fishermen. In fact, the canoe that Samantha’s father went fishing in belonged to Mr Jones, and Samantha’s father had to pay him to use it. The day that the old man came to town, Samantha’s father had gone fishing even before the sun had risen. But Mr Jones had stayed in bed. When the old man came to his house, he took a long time to come to the door. And when he eventually came out, he looked as though he had just woken up. He was still wearing his pyjamas and rubbing the sleep from his eyes.

‘Yes?’ said Mr Jones. ‘What is it? What do you want?’

The old man asked him for a glass of water, and at first Mr Jones couldn’t understand him, because of the old man’s strong accent. The old man said again that he wanted a glass of water.

Mr Jones said, ‘No, you can’t have a glass of water. I’ve run out of water.’

Then he went back inside and slammed his door.

The old man went all through the village. At every house it was the same. Rich or poor, friendly or unfriendly, the answer was the same. ‘We’ve run out of water!’ You see, it was hard for the villagers to get water, and they didn’t want to give any of their water to a dirty old man with no money. There weren’t any roads or streetlights in the village, and so of course there weren’t any taps, either. The villagers got their water from a well, but it was in the hills, a long tiring walk away from the sea and the village. And the day that the old man arrived at the village was in the middle of the dry season, when there wasn’t even very much water in the well. So at each house, the old man would be told ‘Sorry – we’ve run out of water!’

Eventually, the old man had been to every house in the village except Samantha’s house. Samantha was sitting on the steps of her house, playing with her baby brother when the old man came along. He had just been to Samantha’s neighbour’s house, where he had been told that the neighbours were very very sorry, but unfortunately they had run out of water just that morning.

It took the old man a long time to walk along the sandy path to Samantha’s house. It’s always tiring to walk in sand when it’s deep and the weather is hot, and the old man looked weak and tired and he couldn’t walk fast. When he arrived, he asked Samantha in his funny accent if he could please have a glass of water. Like this:

‘Hello, little girl. Please could you spare a glass of water for a thirsty old man?’

And Samantha said, ‘Of course. Just wait there and watch my little brother. I’ll go and get you some.’

Samantha said this because she had been well brought-up. And because she was a friendly and helpful person by nature. She went to the back of her house and filled up a cup with water. Then she brought it back to the old man.

‘Thank you, thank you!’ said the old man. He threw his head back and drank all of the water. While he was drinking, Samantha noticed something rather strange. The old man was wearing a necklace made out of a piece of string with a funny leathery thing on it. Hold up your hand again. You see this finger? That’s what the thing looked like. A tiny finger, very long and narrow, with a little fingernail on the end of it. Samantha knew what that meant. The finger was the magical finger from the famous monkey. And because the old man was wearing it on a necklace, Samantha knew that he must be a WITCH.

‘Ah-ha!’ said the old man. ‘I see you’ve noticed my necklace!’

The old man said this in a much louder and stronger voice, as if the water had done him a lot of good. And he was standing up a lot straighter, too. In fact he seemed very tall indeed, almost as tall as the little house where Samantha and her family lived.

‘Well little girl, you’ve given me something. Now I want to give you something in return – some advice. Make sure that you and your family go to the well this evening to fetch water. Because all of your neighbours have such trouble with their water and they keep running out, I’m going to give them more water. Lots more water!’

Then the old man who was really a witch laughed a long and terrible laugh: AHAHAHAHAHAHA.

When he had finished laughing, he handed back the cup to Samantha and strode off very quickly in the direction of Many Bones and its poisonous tree. Samantha’s little brother started to cry, and Samantha had to take him inside and tell him a story before he would be quiet again.

That day, the canoe that Samantha’s father rented from Mr Jones had started to leak, so he came home earlier than normal and without any fish. Samantha’s mother had been in the forest collecting fruit. They both arrived at the house at the same time, and Samantha told them the story about the old man and his strange necklace and his even stranger advice.

‘Of course,’ said Samantha’s mother, ‘we do need to visit the well now. Whoever this old man was, he’s drunk half of our water.’

‘Yes,’ said Samantha’s father, ‘and it would do the children good to have a walk.’

‘Quite right,’ said Samantha’s mother, ‘and you should perhaps bring your fishing nets. We wouldn’t want anyone to steal them while the house is empty.’

‘Good idea,’ said Samantha’s father, ‘you should bring the nice blankets with you, too.’

And neither of them gave any sign of being worried, as they dressed Samantha and all of her sisters and all of her brothers in all of their clothes, and quickly went around the house collecting as much as they could carry.

‘Come on, come on!’ they said to their children. ‘It’ll be dark soon and you won’t be able to see the path to the well!’

So Samantha and the rest of her family went hurrying along the path to the well. But they had only got as far as the first small hill when they heard an enormous noise - the noise that a snake would make if it wanted to play a joke on you and hissed right in your ear, SSSSSSSSSS!, only even louder than that. From the little hill where they were standing, Samantha could see all the houses of the village, then the sand dunes, and then the sea. Between the houses, water was spraying up into the air, like fountains that were taller than the trees in the jungle. That was making the noise.

The houses and the bushes of the village started to tilt sideways and then, all at once, they started to sink downwards. At the same time, the water from the fountains was collecting to form pools. Then the pools of water between the houses were spreading and joining, forming bigger pools. The houses were sinking down and the water was rising up, and soon all of the roofs of all of the houses had disappeared below the water. And then even the tallest palm trees had disappeared under the water, too. The water spread all the way to the bottom of the hill where Samantha and her family were standing. After only a few minutes, where the village had been was a large lake, with jets of water shooting upwards from the surface. Then, all together, the terrible jets of water seemed to run out. They became weaker, and as they became weaker they became shorter, until they were only the height of a fountain that you might find in someone’s garden, then they were just a sort of bubbling and frothing on the surface of the lake, and then finally they weren’t there at all. There was just the lake left, looking like it had been there forever, stretched out between the sand dunes and the little hill. Samantha and her family were standing on the hill, looking at the lake and right in the middle of them the old man was standing – although nobody had seen him arrive.

‘There it is!’ he said, in his big witch’s voice. ‘There is Lake I’m-Sorry-We’ve-Run-Out-Of-Water.’

He laughed his horrible witch’s laugh and at that point the sun went down and he disappeared.

Samantha’s family all gathered together and wrapped themselves in the warm blankets that Samantha’s mother had brought. Samantha was very frightened and she didn’t think that she would fall asleep. It was very dark and she could still hear the noise of the sea and the shhh noise that the wind made in the bushes on the little hill. Eventually she did sleep, after all.

In the morning Samantha’s mother and father went down to the lake. Samantha’s father dipped his hand into the water and drank some.

‘It’s fresh,’ he said ‘not salty.’

Instead of answering him, Samantha’s mother screamed – she had just seen a big green crocodile swimming over towards them, which would be enough to make me scream, too, and probably you, even though you’re very brave.

‘Look! That crocodile ate Mrs Smith!’

Sure enough, by some unlikely accident the crocodile was wearing Mrs Smith’s multi-coloured straw hat.

Samantha had come down the hill quietly, without her parents noticing. Now she spoke.

‘I don’t think it ate Mrs Smith. I think the crocodile is Mrs Smith.’

Samantha was pointing to a second crocodile, basking in the sun further along the bank. The second crocodile was dressed in a torn pair of pyjamas.

‘And I think that one is Mr Jones.’

‘It’s nice that they can still enjoy the water,’ said Samantha’s mother, as they hurried up the hill away from the crocodiles.

(That all happened a very long time ago, now. The poisonous tree at Many Bones has long since poisoned itself and blown away on the same winds that used to carry the deadly smell to its victims. Now if you visit, there is a town at Many Bones. The people in the town have lots of cars and there’s even an airport, although no motorways yet. And the town isn’t called Many Bones anymore. Now the place has a French name, but there is still a lake nearby, between a small hill and some sand dunes that lead to the sea. The lake is called Lake I’m-Sorry-We’ve-Run-Out-Of-Water. There are crocodiles there, but you won’t see them unless you’re very lucky. They spend most of their time at the bottom of the lake, in the old houses where they used to live.)

-

Q&A

MB: Hey. So, why did you write this? What was going on when you wrote this?

NB: I was living in Madagascar, where the story is set. I was talking with a friend about writing, specifically writing for children. She asked to see an example of something I'd written, I realised everything I'd ever written was terrible up to that point, so I wrote this instead. One thing that I really look for in a story is narrative - fundamentally I think that's why people tell stories - and I'm congenitally incapable of writing narrative, which leaves me a bit stuck. I suddenly realised I could just steal a story and I'd only have to worry about the sentences and the punctuation and so on.

MB: When did you first hear this story?

NB: Madagascar is full of stories, and I'd heard several surprisingly consistent versions of this story when I asked why a local lake was called "Lanirano", which is Malagasy for "Run-out-of-water". I was living in a town called Taolagnaro and the road out of town goes past this lake, and the shore is the perfect length for telling this story if you're walking, so I'd heard it and enjoyed it several times before I wrote my version down. I also included references to other Malagasy beliefs in the story. The poisonous tree part was one of several wildly different explanations for how Taolagnaro had got its name, and I picked it because it was the one that I liked the most. The monkey's finger part is also kind of true, if you're willing to upset some biologists and call a lemur a monkey. It's also very obvious in retrospect that I'd never seen an aye-aye's finger at the time that I wrote the story, as they look genuinely weird and magical and not at all like a human finger.

MB: You mentioned privately that you consider this something like a "just so" story. What does that mean to you?

NB: I meant this completely literally. My parents and teachers read out a lot of Boys-Own-Adventure style books from their own childhoods to me, and the books left an impression. That includes Kipling and the Just-So Stories. Fundamentally, this is a children's story, and it's also a story about how an [X] got its [Y], in this case "lake" and "name" respectively. So it felt natural to channel Kipling pretty directly here. I even thought of starting the story with "Oh Best Beloved", but y'know, show don't tell and all that.

MB: Do you think there's a right way and a wrong way to process a folktale (especially one that comes from a culture that's not your own)?

NB: This is a tricky question right on the heels of saying that I'm aping Rudyard Kipling, since the guy literally wrote "The White Man's Burden" and was firmly into empire and colonialism, whatever his qualities as a writer. And I suppose that you could argue that even the non-extremely-problematic Just-So Stories are still quite patronising: "hmm, I'm going imitate other people's creation myths and use them as stories for children". And perhaps that's something I'm guilty of here. Plus, I did just describe myself as "stealing" a story. Then again, to play devil's advocate and to defend myself a bit: stories and story-telling in rural Madagascar are really important, in a way that's obvious even on passing acquaintance, as they underpin an important system of taboos called fady. Ask any question about an individual's or a community's fady, and you get a story in return. These stories are taken seriously to a greater or lesser degree by adults, but they're initially passed on in childhood, so - like all good children's literature - they'd be better characterised as "stories for everybody". The stories are still alive and wriggling and a good tale deserves to be told, and then of course to be given an Aarne-Thompson number or whatever. (Speaking of which, one of the things that I like about this particular story is how universal it is: I kept the setting, but you could do a cover version in the Swiss Alps and it would still make sense.) I hope that in writing it, I've highlighted some of the things that I love about this particular story, and about Madagascar in general - people's resilience, good humour and generosity - and haven't tried to step too far into the shoes of someone who does actually live in near-unimaginable poverty, trying to feed their family by going out fishing in a rented dug-out canoe that turns over in rough seas. Aside from questions of appropriation, that would be a much more harrowing thing to explain to a kid than a vindictive witch.

MB: Do you have other stories in this mode?

NB: Not really. I find this "voice" easy to do and so it seeps through in other work, where it's unwelcome. I want to write deeply earnest, unreadable stories about the existential struggles of well-off middle class dudes like myself and about our unbearable protagonist's longing glances at the woman who has finally and justifiably dumped him and about the sinuous blue coils of his cigarette smoke as they slowly unravel towards the ceiling. Instead what comes out is light-hearted fairy stories where it turns out that I'm the villain and everyone else lives happily ever after.

MB: Why did you choose to include the… I don't know what to call them. The bits where you speak directly to your reader and give him instructions, work to do outside the reading of the text, etc. "Stand up, make a ring with your arms…" Did these moments just seem natural in the moment?

NB: Well firstly, the reader is a girl, called Samantha. And I'd characterise her more as a listener. The story is written as one that's intended to be read out by an adult, although of course it doesn't have to be, and as far as I know never has been. This is how I would say stuff to a kid, in the absence of "look, check out this photo of the bay I'm talking about", which doesn't work well outside the context of a picture book. And thankfully this is children's fiction, so you can be a bit more playful with things like that - for example, there's no fourth wall to break, because the story is supposed to address the audience. So to my mind, it's sort of the written or spoken equivalent of a pop-up book. Maybe it seems unusual because on the one hand, these landscapes aren't imaginary and I think that they're worth describing, but on the other, descriptive passages aren't typical of the kind of children's fiction that I was trying to write here. So I suppose that this was my way around it, and if it works and it's evocative, then hopefully it's permissible (whether the reader or the listener actually physically raises their arms or not...).

MB: Read anything good or terrible recently?

As you know, I'm definitely going to write a book about vampires, and how they get undeservedly good press when they're secretly extremely boring. As research / procrastination I decided to read Salem's Lot. Jesus that book is long. It's like eating fifteen loaves of plain white bread one after the other. I don't know about terrible, but it's very very long and as a piece of horror fiction I have other issues with it, too. However - and relevant to folktales - there was a reference somewhere in it to "Bluebeard's wife", which I hadn't heard of, so I looked up the story. And there's a very nice modern spin on that folktale by T. Kingfisher, which you can read online (http://tkingfisher.com/?page_id=212). The last complete novel that I read for the first time and really liked was "The Story of My Teeth" by Valeria Luiselli. I read it before she came to the Bookworm Literary Festival here in Beijing. It's superb and very funny and plays skillfully with the symbiosis between stories and reality, as well as voices, characters, books-as-physical-objects and the issues around translation, which are all things that fascinate me.

-

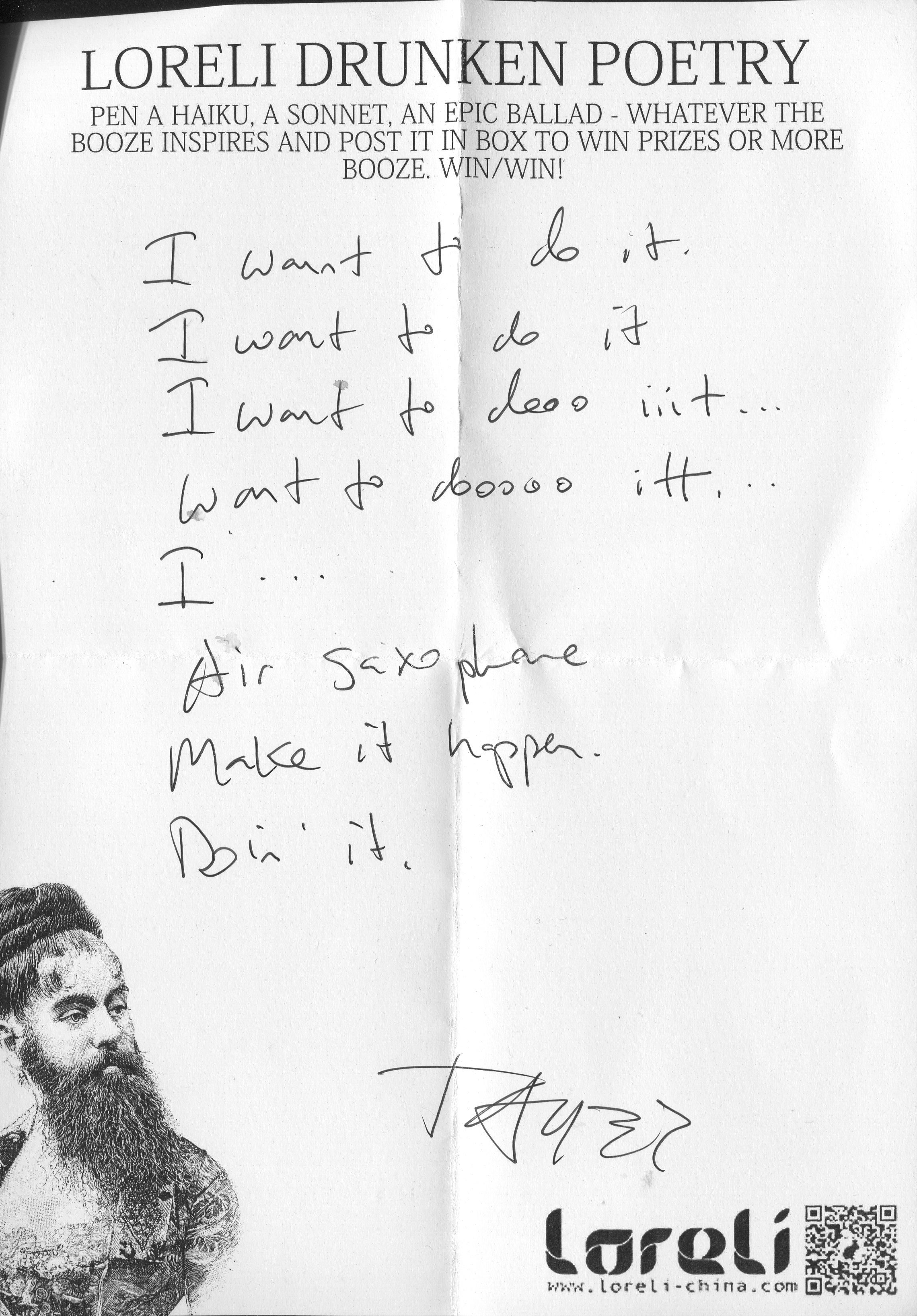

Special Edition:

Drunken Poetry

Gettin' high and low with dragons

Last year, at the Loreli launch party, the three original ladies of Loreli hosted a segment that turned out to be a smash hit: drunken poetry. This year, we brought the crowd favorite back and got some pretty damn good results. Take a look!

Judith and Anna making it funky one dum at a time

sending vibes - that's what drunk poetry is all about

hehehehe hehehehe

And the legibility continues to decrease at an exponential rate...

20 Qing's for 2 Dao's

Is someone drunk?

It's never what I think it is, is it?

Now onto the gags. Prepare yourselves!

Oh Amy, you graceful so and so

There's a story behind this one, I promise.

Since Loreli started, we've received an (almost) overwhelming amount of attention from certain individuals in the form of dick pics. Very classy. So at the party, longtime Loreli friend, menace, and in-house makeup artist Kelly composed this highly conceptual poetry/visual arts mash up for us. Thanks Kelly.

LORELI LOVE

And boom! Due to limited space and loss of certain poems because someone got too drunk (oops), we can only feature a selection of the fine, fine poems from the glorious night that is last Friday. Huge appreciation for everyone who participated and made us laugh like idiots on stage. Best drunken poems I've ever read.

2 Poems by Caleb Washburn

Back from the the holiday with new work from Caleb Washburn. A a poet from Kansas City, Missouri, Washburn received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh. His work has appeared in, or is forthcoming from, The Atlas Review, Bat City Review, Fairy Tale Review, The Journal, The Laurel Review, and Vinyl, among others. He is the managing editor of the online journal Twelfth House. His work is definitely worth more than a preliminary google, so follow those links and keep your eyes peeled for the relevant journals. You may also have the good fortune to catch a live reading at a future Spittoon (keep your ears open).

A q&a follows the work.

-

The Ground Cannot Take Me

I sang the news of the day

but no one thought it beautiful

We don’t want requiems

I sang them too poorly

I am a thing of the air

and dark and low

But still I just want one day to sink

deep into the ground and turn

my sight up to the sky

Yes, that’s it

To love something but not need it

(I have always been so bad at this)

To squint when looking into the sun

or at a cute boy as blinding as the sun

It is so hard to still want something

to find it desirous when looking

at it head on

I have been a god all my life and lonely

Nothing can prepare you for that

-

Love in the Era of Drones

1.

We do not flock. We do not forage. Fish shoal. Insects swarm. I’m not going to say I’m jealous, because what is jealousy but another motivation I don’t need. What I’m saying is you’re better off with me and I’m not standing still.

2.

Shirk the 24/7 lifestyle because it’ll never get it done. My nights are more about a kind of resilience than empathy. I read The Times subliminally and you are too old. You need a penchant for the absurd which you build up like a thick skin, a second skin you wear like pride of country, pride of knowing. Be proud of me and I’ll show you all the places nobody knows about—the rocks I’ve hollowed out in the middle of empty fields, the caves that wait like tongues for water.

3.

There are more ways to lose your lover than ever. There are more ways to love your losses than ever. These are songs as old as gypsum, as cold and smooth as alabaster. Sing me the new shit and I’ll go all filibuster. My lover loved him some destruction ‘til he died.

Q&A

MB: Let's talk about the drone stuff first because that seems to me like a self-contained mode. What brought you to drones? And if you were chewing on American-foreign-wars stuff, what makes drones particularly inspiring to you?

CW: Ever since I was a kid I loved photography, and even removed from the militaristic frame of drone cameras, the camera and photograph themselves have always been able to awe me. I always attached a kind of mystical quality to just the camera itself.

But then you attach a camera to a device that can fly at silent and invisible heights and be able to capture in absurd detail the huge tracts of land it is flying over, you film in infrared so they see through buildings, and then you attach to that missiles that are accurate to a shoebox, and you control all of this from the other side of the world via satellite, and like this was all very terrifying to me like way before I got to the missiles.

But I don’t think my poems actually do a very good job of engaging with the political or militaristic implications of drones all that well. Instead, I’ve used talking about/through drones as a way to tap into a kind of fervency.

The first drone poem I wrote was a retelling of an Old Testament story, of when Isaiah becomes a prophet, and ever since I’ve been interested in writing about drones as a way to tap into that kind of pitched up, intense lyric, where a celestial being can place a burning coal to your lips and call it a blessing. (I also can’t think of a better analog for America’s foreign diplomacy, and its spread of democracy through bombs, than calling a hot coal pressed against lips a blessing.)

MB: Is there a right and a wrong way (for you) to do politics in poetry? (Or is all poetry political?)

CW: To answer your second question first: in the sense that, yes, all utterance has political implications, yes all poetry is political. But I think that’s a side step away from you first question.

Yes, there are definitely wrong ways to write political poems. I am also not an expert of any kind on the matter; while my drone poems definitely have political elements to them, my experience with drones is entirely theoretical. Instead, they are a way for me to get at something else (this kind of religiosity, fear and dread, a speaker who sees themselves at times as being godlike, etc.).

However, all that being said, what I do know about not writing a bad political poem: your / your speaker’s positionality matter, and you need to be aware of how you’re positioning your speaker. If, for instance, you’re writing about the 2015 Tianjin, China explosion that killed over 170 people, but your speaker is an expat in Beijing who keeps ominously referencing the smog and his concern for his safety as an expat, then you’re missing the point. When the poem can only filter the tragedy through the speaker’s perceived lack of personal safety, it fails to engage in the weight of the event itself.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, I want to point to Solmaz Sharif’s poems; in her debut book, Look (Greywolf Press), she also engages the topic of America’s drone warfare, but does so in a way that I think is far more successful than mine as political poems. The reason I think they are successful as political poems in a way that mine are not is that their heat, their oomph comes from making the weight of America’s political decisions actually felt. Whereas my poems are interested in drones as metaphor, Sharif’s poems give glimpses into the lives of those effected by this warfare.

MB: As someone who writes about drones (whether they're on the periphery or at the center of a poem) has living outside the US changed the way you write about living in the US (or do you not feel like you write about living in the US)?

CW: The poems published above were written when I was still living in the US. I haven’t written any drone poems since moving to China, but I had also stopped writing them in the couple months leading up to my move. I don’t think the move caused me to stop writing about drones, but instead I just found new ways to obsess over the same kinds of ideas.

Yes, moving to China has changed my writing. While I’ve done a decent bit of writing while here, I’m still figuring out what it’s doing. I don’t think I can really say more about it, though. I usually need a lot of time separated from my work before I can kind of get a feel for what was going on with it.

MB: I love this line, which I consider the non sequitur equivalent of the rabbit punch: "I read The Times subliminally and you are too old." Also love this triple-decker simile: penchant for the absurd [is like] thick skin [is like] pride of country. Is this the primary function of the absurd? (To protect us.) Another way to read this question: what's the function of the absurd?

CW: Keep up.

MB: I'm not sure the poems we're running today on the site are representative of this but I love your body stuff, man. You treat sex like a mystic and I'm not used to hearing that work, but we crave it (a mystic approach to sex). There's always a tension (contradiction): sex is "just" sex and not important compared to some other thing, but the sex drive can also strand us in strange places, amazing places or terrible places. If I had to twist this into a question, it would be: when you write about sex or the body, do you feel like (as a poet) you are processing your own feelings, or like you are building something consciously (outside your own life)?

CW: When I write about sex, I’m not writing about my sex life, or even my sexual interests. I think if I were to, that would be really boring. For me, sex is just a situation that I can superimpose other ideas over. A recurring obsession of mine is desire or longing, and masking different kinds of desire as sexual desire has seemed pretty fruitful for me.

MB: Another thing that keeps coming up (here we see it in The Ground Cannot…) in your work is a dispersed personhood, or a person wanting to be lots of places he can't be. If I got the title here, you're adding that the longing to "sink/ deep into the ground and turn/ my sight up to the sky" is not realistic. Have you figured out any secrets for getting out of the human body or are we pretty much stuck here?

CW: I really like that reading of the title, as a kind of refusal of the ground. “The Ground Cannot Take Me.” Huh. I’d never thought of it like that.

Unfortunately, “sink[ing] / deep into the ground and turn[ing] / [our] sight up to the sky” is all too realistic, in that it happens to anyone who has a common casket burial. Or is that fatalistic?

MB: How has your poetry changed since you started writing poetry?

CW: I don’t know, I’m still very much in my early writing stages. What’s changed is that I’ve read more now than six years ago.

MB: What are you working on right now?

CW: I really can’t say, although that’s not me just being oblique. I’d describe it, though, by saying that my lines are getting longer and are becoming slightly more aphoristic. I’m a little more interested in the unit of the sentence, rather than the line (which might mean I’m writing prose??). The poems also feel more emotionally vulnerable, which is what scares me (so that’s what I’m pushing towards hardest).

MB: Read anything cool or terrible recently?

CW: I’ve been reading a lot of (and about) Anna Akhmatova, the great 20th century Russian/Soviet poet. I’ve been reading the new Black Panther comic series written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and I’m waiting to get my hands the spinoff World of Wakanda comics, which will have issues written by the poet Yona Harvey.

It’s a little tough getting my hands on the new collections of poetry my friends in the States talk about, but I’ve made sure to pick up Solmaz Sharif’s Look, and Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds, which are two debut books that set the bar so high.

READ ARCHIVE